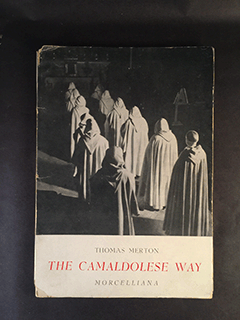

One doesn’t associate Merton with mysteries—except, perhaps, Divine Mysteries.

This Merton mystery involves a particular book. A particular copy of a particular book.

I’ve tried to describe the pace at which books pass through here at the Wonder Book warehouse in Frederick, Maryland. If I’ve already recorded this scene as simile forgive me:

There was an I Love Lucy TV show episode in which Lucy was hired to pack chocolate candies into gift boxes. Lucy stood behind a conveyor belt and the candies slowly paraded in front of her. She had no problem packing them. She would pluck one at a time as they came toward her and place it carefully in the box. Her supervisor came in and saw how well she was doing, and the conveyor was speeded up. Her packing became more frenetic as candies flowed before her. Finally, she could no longer keep pace and she began stuffing chocolates in her mouth and apron pockets and down her blouse. Finally, the candies became a torrent, and she rolled her eyes in resignation and the chocolates flowed so quickly they flew off the end of the conveyor belt onto the floor.

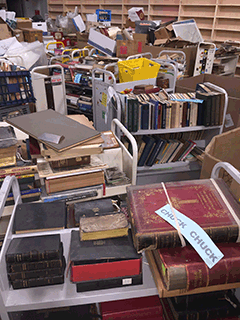

The work we do here can be much like that. So many books flow in we can barely keep from backing up sometimes. Thousands are in storage in boxes on wooden pallets waiting to be evaluated. We have about a dozen large trailers full of overflow as well. But we just cannot say no. If we don’t take the books, there’s often no one else. I always worry, for the books we can’t accept could go to…bad places…if we don’t accept them.

Anything that slows us down here causes the backlog to build. We don’t want to run out of storage space entirely. Sometimes we come close.

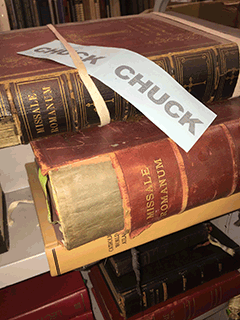

Where the book in question came from I don’t know. There are currently about 15 wheeled metal carts (6 shelves with 3 linear feet per shelf) loaded with books and other things for my attention. These are put on carts by sorters trained to put aside different generic kinds of books and photos and ephemera and…stuff that they are unsure of or suspect may have collectible value. Also, most of the foreign language books are carted with blue slips on them that read “Chuck.”

If nothing more interesting is happening (i.e. usually), I spend my weekends looking through these carts.

I can’t recall on what kind of cart this book came to me, but I suspect it was mixed in with some European language publications—maybe it was among old books and guides from someone’s Grand Tour?

Anyway, I believe the fact that it was Merton and not a title I was familiar with caused the slim softcover to “stick to my hand.”

Thomas Merton is an author who continues to sell very well to popular culture readers as well as academic and religious scholars. His books are also still “collected.” The ABAA.org website offers a large selection of his works—many going for hundreds or even thousands of dollars.

It seems we can never have too many copies of his books for the Internet stock or the three brick and mortar stores. If it is a first edition or there’s something unusual about a copy, it goes to “Research” to verify its bibliographic points and to try to put a fair value on it.

I put The Camaldolese Way aside to look more closely at some time in the future. I set it onto a “secondary” Chuck cart—along with other “tough” problems that cant be evaluated immediately or punted off to someone else here.

How and why this book came to my hand again recently, I’m not sure. There are times I think that perhaps there’s a bit of “Divvie” in me. (A Divvie is someone who deals in collectibles who seems to be able to “divine” that an object is special just by handling it.)

This book just “felt” good.

But if I am able to occasionally find an autograph in a book just by “feeling” it is signed and deciding I should open that particular volume and look inside; or if some instinct tells me there is something extraordinary—like an autographed letter laid in the back I often wonder: How many slip through?

Do I miss a few every month?

Or dozens?

Or hundreds?!

It is quite worrisome and often keeps me awake nights.

“I don’t let you miss much.”

Ahh, that would be my Book Muse checking in. For so many years now she has appeared to “help” me discover things I might otherwise have missed. From single items to vast opportunities—at least according to her. Sometimes I wonder if …

“Do you want to see how you’d do without me for a bit?”

“No. No. I’m glad you’re here! It’s been a while. Been away in Tir Na Nog or somewhere?”

“I check in now and then. Just to keep you on the straight and narrow. Sometimes you’re just too busy to notice.”

“I AM sorry. I’m glad you’re here. I always am—eventually. So you put the special “glow” on this book?”

“Perhaps… I’m not telling. But just get on wi’ it will ye. And if ever I’m being a burden to ye, just you let me know.”

“Never.”

“You needn’t say “Thank you” or show any appreciation if you’re not sincere.”

“I AM. I do. I …”

“Eedjit.”

Ummm, where was I?

I set the booklet atop the research desk—fast tracking it to the front of the line.

There’s a scene in the film Being There where an investigative reporter in a Washington Post type office tells her editor she can’t find any history of the movie’s protagonist: “Chance the Gardener.” His past is a cipher. She tells him, repeatedly, I’ve looked everywhere and there’s no previous record of his existence.”

“Check again!” the editor insists.

“I’ve checked everywhere!”

“Check again.”

“Screw you. I quit.”

A few days later I passed the research desk and there it was. The results written on a 3×5 card inserted into the book were “Nothing online. None on WorldCat.” (WorldCat is a huge online database of university and other institutional libraries’ book holdings. If there are no copies of a book showing up in the Library of Congress or the British Library or the hundreds of university and organization libraries and book collections around the world—well, that is arresting. It doesn’t mean it is something “great” but it does mean it is “something.”)

Unless there’s something wrong with the search.

“There simply can’t be an unrecorded Thomas Merton work,” I thought.

Forgetting Being There, I wrote “Check Again” on the 3×5 card and set it again on top of the pile on the desk waiting to be looked up. That pile on the desk is just the tip of the iceberg here.

There is a mountain of books set aside in tubs behind it waiting for their turn to be evaluated manually and with a trained eye.

Well, Madeline is patient and didn’t write in an expletive or quit, but her response on the 3×5 card was terse:

“Same results. Nothing.”

Hmmmm…I better check myself. (Not that I’m nearly as good as she is, but before I put my name to something I thought I’d better triple check.)

Nothing?

Nothing.

I checked in a few other places as well.

I decided to punt the thing to my more learned colleagues on the ABAA internal Discuss listserv.

I got a few opinions from booksellers far more experienced in the arcane than I.

It is apparently not located in any major library in the world. There is apparently no record of a physical copy of it anywhere.

It is not listed in Merton bibliography by Dell’Isola.

One specialist in Catholic books, Owen Kubik, opined it was likely off-printed from a larger work in Italian—Vita Nel Silenzio (“Living in Silence”)—and translated back into in English. He went on to add that perhaps the monks from the Camaldolese community in the mountains of central Italy produced this themselves as an informative and/or promotional tract about themselves and their monastery.

The back of this book credits that book and says: “From Vita Nel Silenzio…published in Italy…December 1956.”

That makes some sense. WorldCat does locate 12 copies of Vita Nel Silenzio. 2 in the US (one in Kentucky—likely from someone at the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani—where Merton spent his last years. 1 copy is in France.) The rest are held in Italy.

I decided why not check Wonder Book?

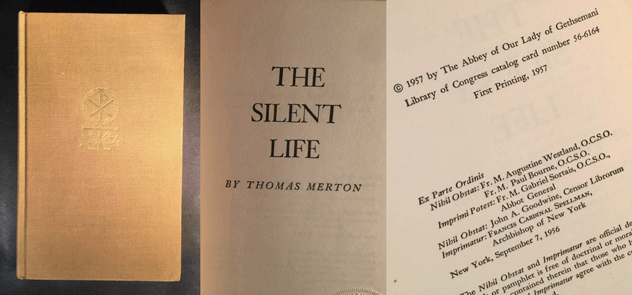

Sure enough we had two copies of the English edition online at WonderBook.com: The Silent Life. I asked an assistant to pull those copies. Turns out one of those is a first edition hardcover—albeit jacketless and ex library.

How had we missed it? Well, it is a bit worn and humble looking. On first glance nothing more than a reading copy.

Oops!

…Still it isn’t worth much.

The first edition published by Farrar, Strauss and Cudahy is a small format hardcover. It is copyrighted by the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani 1957 and the copyright page states: “First Printing, 1957.” It is 178 pages long.

In 1941 Merton joined the Trappist monastery Abbey at Our Lady of Gethsemani in Kentucky. He lived there the rest of his life. (His death was in Thailand in 1968 where he was attending a conference. He was electrocuted in the bath. He body was flown back to the United States. He was buried at the abbey in Kentucky. He was 53 years old.)

The second copy was a 1950s mass market paperback edition.

An online source has this to say about The Silent Life:

This book, unlike many of Merton’s writings, is specifically targeted at those who are exploring the monastic life. It is Merton’s fairly academic approach. He starts in a way that resonates clearly for all readers…’No one can find God without having first been found by Him. A monk is a man who seeks God because he has been found by God.’ And so the door is open to the Silent Life.

So, which came first? The Italian version or the English? I wouldn’t think Merton wrote the book in Italian. So, apparently there was a little printing error (or license) in the claim on the back of The Camaldolese Way that the text was from Vita Nel Silenzio by the Morcelliana printers in Brescia, Italy. For when I looked closely at the text of the American first edition, the final chapter was titled: “The Camaldolese”. Comparing that chapter and The Camaldolese Way, the text appears identical. But I have found some omissions in The Camaldolese Way. I haven’t compared line by line.

So the conclusion would be the American edition in English came first. M.R. Cimnaghi translated it into Italian as Vita Nel Silenzio. The Morcelliana printers used the English text from the American edition for The Camaldolese Way.

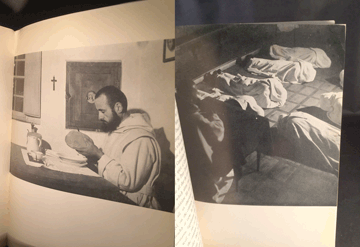

However, there is still some mystery. I’m guessing Owen was correct. This was published by or for the Camaldolese monastery. There’s no hint of recruitment or invitations to visit. There are many full-page black and white photographs that are completely different from the photos published in the American edition of The Silent Life.

But WHY are there no copies of The Camaldolese Way out there?

It is still guess work. Perhaps, if the monastery had them created, they didn’t have many printed, and those that were not broadly distributed. Maybe they don’t get many visitors. Maybe they still have a few boxes there?

It is fun to do a little bibliodetective work and speculation.

But is far more FUN to have this “only” copy!

I’m going to pass it on to Allen Ahearn of Quill & Brush. He requested it. He wrote a bibliography of Merton in his series of Author Price Guides (which he will need to update because of this book!) He will find a good and deserving and permanent home for it. Some scholar can compare the text line for line and see if there’s anything added by Merton in The Camaldolese Way from the text of The Silent Life. Unlikely, but who knows?

And the photographs in the “Way” may be the only surviving images of the Camaldoli Monastery in 1956-57 created for this publication.

There’s a great deal of satisfaction in what we do here: #BookRescue

We’ve added a little star to the constellation of Thomas Merton’s works.

Addendum:

After the copyright page (such as it is) of The Camaldolese Way, the next page has only these words:

“AD INTERIORA DESERTI” *

Is it a dedication?

Googling the phrase in a number of ways yields little. The only likely match I found was from Exodus Chapter 3 when Moses went to the “far side of the wilderness or desert”?* It was there he found the Burning Bush and met God: “I am Who I am!” Or as Merton believes in The Silent Life—was Moses “found” by God? Called, as it were?

I asked Owen what he thought, and he replied:

“AD INTERIORA DESERTI” refers to the interior desert. This is a classic spiritual concept of which Merton was a famous proponent—it refers to the need to live in an interior desert where the soul strips itself of all attachments to worldly pleasures and pains in order to live only for God.

They both work for me. Perhaps that is what Merton and those who pursue this life seek in their ascetic disciplines. They shed off the distractions of society in order to devote all they really own—their mind and body—to seek God in order to “see” Him.

[…] Thomas Merton had a happy ending in a university archive. The Negro Travel Guide is still on my shelves. I like […]