(This was written over 12 years ago. The names of people and organizations are not real. The story has nothing to do with the service “Books for the Blind” or any of the great organizations that help train and/or raise money for the visually impaired. Books for the Blind (a.k.a. Talking Books) is a United States program which provides audio recordings of books free of charge to people who are blind or visually impaired.)

“Books for the Blind. Bob.” Followed by a phone number.

Very many of the phone messages taped to my office doorjamb are scrambled but this one couldn’t be that far off.

So believe it or not, when I found this taped to my door the fundamental paradox of the statement did not strike me as unusual.

This business can be so absurd sometimes. Books can be found in any circumstances. The whys and wheres eventually make sense. Usually.

At first glance I just assumed it was another solicitation for a charitable contribution of books or money. Lots of people want free books—schools, hospitals, jails, the Boy Scouts.

I punched in the phone number and a female voice answered “Blind Industries.” I asked for Bob and as I waited to be put through I wondered—what was this all about? Printed books and people with visual impairments can be kind of a contradiction.

After introductions and pleasantries Bob said:

“I am in charge of donations here.”

“Does he want free books or dollars?” I thought.

“We receive many thousands of books donated to us.”

“Ahhh, ok. Now this is making some sense.”

Though charities tend to receive the most common denominator of book collections, if you got to them early enough before the literate volunteers and scouts and before the table sales creamed off anything of value, you could occasionally buy some good stuff. Remember this was many years ago before we were able to come up with viable solutions to keep “unsalable books” books.

“In past years we’ve had sales. University people in town come and sort our books for us.”

University people—volunteers! Well meaning, I’m sure. But unless you are in the book business, you can make many mistakes. (Schools, Libraries, Church’s charities and all types of organizations use book donations to raise money.) Scholarly volunteers may know much more about the contents of books than I. AND if I had had a “university mind” I wouldn’t be grubbing through dirty, dusty stacks of boxes and pickup trucks loaded with other people’s unwanted books.

But for good or bad, that’s what I do. I am a conduit through which millions of books have passed on their way to new homes. Wonder Book has done a pretty good job since 1980 knowing whether a book can bring a dollar or a hundred dollars or nothing at all.

Sometimes thankfully, other times cursedly, the university people were, despite their erudition in other areas, blind to the difference between bad books, good books, better books and great books. Average books can get priced too high. Rare books get priced too low. The “too low” was the reason book dealers, scouts and collectors used to line up hours ahead of any charity book sale.

I was all ears.

“The sales we have had in past years have been successful, but the site we’ve used has suddenly become unavailable. Someone told me you purchase large quantities of books. We are running out of room here.”

“Yes. Sometimes.”

“Well, they’re all sorted. By subject and value. The boxes are all marked.”

Fascinating, I thought cynically, my work has been done for me.

“Can you come look at them?”

The large building was in an old warehouse district near the docks in the city. Above the entrance it indeed had a sign which stated that it was the “Blind Services.” I entered and asked a guy on a forklift for Bob. Bob was neatly dressed in a white shirt, black pants and plain black shoes. He was short, chubby, and had a band of scraggly dark hair wrapping around a bald pate from ear to ear. He gave me a tour of the warehouse. I fully expected to see blind people employed. Assembling things or performing tasks which the sightless could do to make money and be self-sufficient. It was a mystery to me. I’d heard of blind work programs. As we walked through, I saw no blind people working in this warehouse for the blind.

Apparently, there were no blind people here at all.

“We receive a lot of donations. We are a very successful charity.”

It finally appeared to me. The obvious question.

“Why do people donate so many books to the blind?”

“I dunno, we don’t solicit them,” said Bob. “But we get thousands of them.”

He seemed oblivious to the reasoning behind my question. If I was donating something to the blind, I would assume they would want things they could actually use. Only a second tier of thinking would raise the idea that they wanted to sell donations to raise money.

He walked me to a back corner of the vast warehouse, past furniture, large bins of clothing, sorting tables, old toys and bicycles, all manner of objects people see fit to give away until I saw the familiar sight of boxes stacked atop pallets.

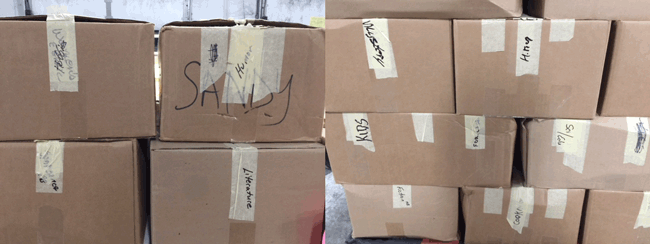

Four or five pallets. Each holding thirty, forty, fifty identical boxes of books.

“We’d like to find someone to buy all of the books we receive. Obviously our clients can’t use them. Finding another site for the sale and rounding up enough volunteers to organize it and run it is a huge problem for us.”

We reached the pallets, and I saw that each of the taped-up boxes had notations written upon it.

“Literature, crafts, art, coffee table, popular fiction…”

“May I look at some?”

Bob said yes. I opened the little Laguiole jackknife on my key chain and began popping random boxes open.

They were… okay. Not the worst charity books I’d seen. The university volunteers who had sorted them had done a decent job. The categories were generally correct and the junk to salable ratio was not bad.

Bob then led me over to the corner with a few pallets of boxes where each was marked “collectible.”

I popped open some of these. Well, one person’s collectible is another man’s junk. In many cases, the university volunteers’ notions for what made books collectible were way off the mark. Actually, about nine out of ten times was my initial estimation.

Old meant collectible to them. Old usually just meant old to me. About 95% of old books—80 years old or older—have no reader or collector market. Maybe 99%. Big and flashy often meant collectible to them. Well, same story. Older editions by famous authors were abundant. Who knows, they might be first editions but not likely. Rare books are “rare.” One out 10,000 old books are really valuable. Some think finding a vintage Hemingway or Faulkner is treasure. But almost all are not 1st editions. It can be pretty tough tell. But I knew. These weren’t. Plus the absence of dust jackets usually turned these would be collectibles into reading copies or worse.

Still, boxes containing a small percentage of collectible books were not so bad. Going through thousands of books looking for the few that have value and should be “rescued” is fun—for me anyway. It is like panning for gold.

Bob said, “What I’d like to find out is what you’d be paying for them and then we’d try to build an on-going relationship for future donations that come in.”

I looked at more boxes.

We did the “dance.” I offered “X” per box. He countered. “Can’t you go “Y”? We came to an agreement.

“That would be the delivered price.” It would cost a lot to send a truck down here and Clif, the warehouse manager, hated driving the big box truck in the city. I had observed numerous box trucks with the organization’s name on the side in the parking lot outside.

He tugged at his chin. He hemmed and hawed and shifted from foot to foot and asked for more, but I held firm and soon the delivery date was set for the first truck load.

On that date, Bob arrived at the warehouse in one of those box trucks. The driver was a tall, thin, middle-aged man who bore all the physical signs of having had a real tough life. Bob introduced him as Leroy. Bob instructed Leroy to begin unloading the boxes while he stood supervising with his arms folded over his chest. I called in a few helpers from my staff and soon the Blind books were mine.

I did the math mentally and multiplied the boxes by the dollars. I went to my office and returned with a check made out to the Society.

Bob held it up scrutinizing it closely as if he was nearsighted. Making sure there was nothing wrong with it I suppose.

“When can we bring more?” he asked nervously.

“I’ll let you know when I’ve gone through some.”

The books were fine. Worth what I paid for them. So when he called a few days later asking how soon he could bring more, I agreed to accept another truck load the following week.

When the pair arrived, Bob was a bit agitated. He complained how expensive it was bringing the truck up from the city. He hemmed and hawed and shifted from foot to foot and asked for more money.

“I wish I could,” I said. “But I’m happy with the deal we had. You can take them back if you want.”

His eyes widened in near panic:

“No! No! We’ll do it this time.”

As we were unloading, Bob—supervising from a convenient distance—noted about twenty boxes of jumbled books in boxes on our loading dock. They were mostly old series romances, obsolete text books and book club novels by long forgotten and unsaleable authors. It was pretty clear that those books were on their way out.

“Just junk we’re going to toss. (At that time there weren’t any companies recycling books into pulp paper.) You want ’em?” I laughed.

“Sure!” Bob responded.

Hmmm. If he’d been selling me all his books and I haven’t seen any junk like this in them, why would he want them? His university people must toss this kind of stuff out just as we do. But why not? It’s easier for us to put them in his truck than to carry them out to the dumpster. Besides, if he can use them, that’s great, it’ll keep them out of the landfill.

So when we had off loaded two hundred and fifty boxes or so from his truck, we put the twenty or so boxes of ours on the truck.

It was only then I noticed.

Leroy had dropped out some point and was standing next to Bob watching us do the work—serving as assistant supervisor I guess.

I wrote the check. Bob again seemed to read each letter and number. His nose only a couple inches away. Checking the spelling and addition, I suppose.

“We’ll be back next Tuesday,” Bob said matter-of-factly.

Why not? The deal was fine.

“Same price?” he asked, his tone and inflection seeming to hold out hope for a raise.

“That’s fine,” I confirmed. “Do you want us to save more of these rejected books for you?”

“Oh, yes. We’ll put them to some use,” he answered eagerly.

The next Tuesday we went through the same drill, only it seemed Leroy dropped out earlier this time. We had put aside about seventy-five boxes of junk books to give them.

I turned to go to my office to get the big metal One-Write checkbook I’d used for over twenty years. I picked it up from my desk and turned to find Bob’s bald head only about a foot from my nose.

“I’ve created a new division,” he said excitedly. “I want to encourage more donations from the public. We’re calling it ‘Convert It To Cash’ so people feel like the goods they’re donating to the blind are going to good use. Do you like the name?”

A bit confused and caught off guard I replied:

“Ummm…sure. I like the idea. People can see their donated objects turning into assets which the blind can use to acquire things they really need.”

Actually, it’s also weird, I thought. But I made the check out to “Convert It To Cash.” Bob closely inspected each letter and number at nose length and when he was sure there was nothing awry, he left my office and headed back to his truck.

He said he’d be back again next week.

Ok. Ok. You can call me naïve.

“Naïve?! I’d call you a sucker of the first order for falling for that.”

Ah, my Book Muse putting her two cents in.

“You could have tapped me on the shoulder then and there if you knew.” I countered.

“If I held your hand through your every folly, I’d be doing little else we my time.”

“I know. I really do appreciate all you’ve done.”

“And a little smack of reality does you a bit of good. It reinforces the learning curve. Now get on with the tale and don’t try to paint too good a portrait of yourself here.”

This went on for a few more cycles. He seemingly had an unending supply of books.

He would stand in the same spot and watch the work. He would depart with Leroy, his check in hand, a big smile on his face.

Then I hinted we were getting stuffed and might need a breather.

“Oh, no!” he exclaimed animatedly. He was almost huffing and puffing shifting from foot to foot. “I’d hate to have to find another outlet. We NEED to come back next week.”

He was so insistent. Almost upset. He stressed the word “need.” I assented, and he was visibly relieved. I didn’t want to deny the charity any funds. I didn’t want to deal with an agitated Bob. And “you can never have too many books”—just not enough space.

But I was beginning to feel a little apprehensive with all this. It was too much of a good thing. I felt there was something wrong with the equation. Still, he had the truck and the building and the office with his name on the door.

The next day Ernest, who was sorting the boxes, asked me to come look at something.

“These look like our trash, don’t they?”

He had about ten boxes popped open and set aside and, sure enough, the contents looked like the stuff we were always throwing away only they had been packed into the organization’s boxes and labeled “General Books.”

“They must have gotten them mixed up at the warehouse,” I said.

We’re very busy. Mistakes like that could happen here I felt. I’m trusting. Sometimes to a fault. Sometimes to a sucker.

When Ernest was done with this load was done, we found we had bought back about thirty-five boxes of our own trash.

When Bob and Leroy arrived the next time, they both acted genuinely shocked and assured me that that would have been impossible. When it was done, we ended up giving them back the books we paid for the last time. I didn’t adjust the price. I had been assured that it was not my trash they had brought but trash carefully sorted by university volunteers.

When they were about to leave, Leroy told Bob he’d need gas. He said this loud enough so anyone nearby could hear.

Bob hemmed and hawed and made a show of pulling his wallet out and looking into it and angling it so I could see it was empty.

He asked Leroy, “Do you have some money? I’ll reimburse you as soon as we get back to the office.”

Leroy padded all four of his pants pockets. “I’m busted, Bob. Tomorrow’s payday.”

Bob looked up at me. I hadn’t noticed before but now his eyes looked beady He asked, “Do you suppose you could advance us some cash? We need it to get back. I’ll gladly reimburse you the next trip.”

“No,” I said. This is a business. We don’t do things this way. “I’m afraid we’re not able to do that.”

Bob raised his hand to his chin, tugged it, and put on a thoughtful face. He shifted from foot to foot.

“I wonder how we’re gonna get back.”

Leroy offered, “You could cash that check here in town.”

“But we don’t have an account anywhere around here,” Bob replied.

“The boss here could go to the bank with us and help us cash it,” Leroy offered—eyeing me needfully.

I had no time for that nonsense. I had no time for this game. I was willing to pay for them to go away so I could get back to work. I felt I was seeing too much of Bob.

I pulled out my wallet, took out fifty dollars and put it in Bob’s hand.

He didn’t need to inspect the cash as closely as he did the check. Actually, his eyesight was fine. He could read book titles from a distance. But put a check in his hand and he would eye in up close. Kind of “needfully.”

“Would you like a receipt for this?” Bob asked.

This deal was getting shakier. I foresaw problems.

“No, just bring it back to me on the next load.”

Clif took me aside later and said, “Don’t you think they acted nervous when you told them about the junk books? And the driver was acting weird, like he was on something. Shaky.”

Shaky, my thoughts exactly—only in another way. But I hadn’t noticed. I had been in a real hurry. I was focused on the books and work—not a shaky truck driver.

The next day, Ernest said there were about forty boxes of our junk included in this latest delivery.

I called.

I asked for Bob and was put through.

“Bob Smithers.”

“And Convert It To Cash?” I asked.

“Yessss,” he stretched the word out nervously. “Chuck?” he added, recognizing my voice. He sounded a bit hopeful.

“Bob, we got about forty of our boxes of junk back again this time.” I was angry. Mostly at myself for being so gullible. But the deal had started out so well. It was just that it, well, incrementally began to stink. I couldn’t see taking the risk. Something stunk. I didn’t want to be involved.

“Oh, that couldn’t be,” Bob insisted.

“Oh, yeah. I recognize our junk. They’re culls from our stores. A lot of the books even have our price stickers on them. Anyway, I need to suspend any more deliveries. We’re backed up,” I lied.

“Oh, no. NO! We have so many books here for our clients.”

“You’ll need to find another outlet for them I’m afraid.”

“We’ll bring extra boxes next time to make up for the bad ones.”

“No thanks.”

A few days later Clif found me clambering high atop pallets—a dangerous stunt that was forbidden for everyone here to do. I was looking for a missing book collection we’d bought that I wanted to dip into. It had a lot of aviation in it and there was a dealer coming to town the next week who sold books at air shows. I wanted him to have plenty to look at. And buy.

“It’s Leroy.”

“On the phone?”

“No, he’s here.”

I went to the dock and boxes were already being unloaded. Leroy was pitching in for a change. With fervor.

“Leroy, I told Bob we can’t use anymore.”

“He told me this was a make up delivery. No charge,” Leroy puffed.

Boy, did I feel bad.

As we were unloading, Leroy motioned me aside. He spoke softly, “Boss, Bob said he put in twice as many boxes as you said were no good. He was hoping you could make a donation for the difference.” He then quoted me a price.

I went to my office and wrote out a check. I made it out to the organization for the blind NOT “Convert It to Cash.” I wrote Bob a note on our letterhead.

“Dear Bob. We will refuse any future deliveries. Good luck with Convert It To Cash.”

I went back out to the loading dock with the letter and the check and Clif was facing Leroy with his wallet out. He was counting out money and putting it in Leroy’s hand.

“Gas money?” I asked.

“Afraid so,” Leroy said.

“I’ll give you the money. You give Clif back his money.”

He looked at the letter and he read the check and his eyebrows went up. He smiled. A gold incisor twinkled.

“Nice doing business with ya.”

I thought I’d seen the last of them. Bob never called and I’d put the squirrely deal—good and bad—behind me.

Until one day Clif sought me out in some far corner of the sprawling warehouse.

“It’s Leroy.”

“Who?”

“The ‘Blind’ guy.”

“I told them not to come back.”

“He’s got a woman with him.”

“No Bob?”

“No Bob.”

“What’s he want?”

“He’s got a truckload of books. What else?”

I went to the loading dock. Leroy was working hard getting the books off his truck. He was frantically stacking boxes from the back of his truck onto a pallet on the dock. Perhaps in his mind if they were out of the truck I was more likely to accept them.

The woman stood off to the side leaning against the wall. She was skinny and frail. Dirty with stringy mouse brown hair. She appeared to have the shakes.

I wrote the check—to the “Blind.”

I gave Leroy fifty bucks in “gas money.” The woman’s eyes landed and focused on the green paper.

I took Leroy aside.

“Don’t ever come back. Not you or Bob or anyone. I’ll make some calls if you do.”

“Okay, boss.”

The books were okay. It had been a good deal—even when buying back my own trash.

I could have turned a blind eye—could it possibly be charity abuse? Were they robbing the sightless?

Plus it was all just suspicion. They could’ve just been weirdos. I’d run across plenty of those.

But it left a bad taste in my mouth.

I’d learned long ago—stinky deals weren’t worth it. They cost me guilt ridden sleepless nights.

I’m that sort of guy.

I know—I hope I know—some blind people got some money or services.

And I’d recycled a lot of books.

We found out later those guys had a problem. I don’t know how it’ll ended up for them. The organization was quite legit and did a lot of good for a lot of people. There were just a couple bad apples there.

We never got any more books from though. Maybe they started up a sale again?

Now, all these years later we buy a lot of books from charitable organizations be they sale leftovers or unsorted donations.

A LOT.

And we’ve innovated a lot of ways to keep a lot of “unsalable” books as books. A LOT.

Its what we do here. A kind of mission.

#BookRescue

There are no comments to display.