I never took economics or business courses in college. (Does it show?)

When I took the leap of faith and opened a bookstore in Frederick, Maryland in 1980 it is probably a good thing I didn’t know the facts of commerce. If I had, I probably would have heeded the advice of a number of mature friends and relatives who told me used bookstores were essentially hobbies for retired people or break-even propositions for quirky folks who wouldn’t or couldn’t get a real job working for someone else.

It was once said that aerodynamically a bumblebee should not be able to fly. If the bug was convinced of that by experts and wiser heads, why would it attempt to take off? Why would it take the risk?

When Carl Sickles and I each put a thousand dollars in for the first month’s rent, the deposit and a load of unfinished #2 pine 1 inch thick shelving planks to start the shop in 1980, I had no notions about leases and taxes and licenses and permits and… the myriad of things one had to know and do then to be in business. That was probably a good thing. I guess I thought you just got a place, put some books out and the people would come.

By the way, Carl was a former Civil Servant who operated his store as something to keep himself busy and entertained in his retirement. That may have told me something had I not been blinded by the stars in my eyes.

Once we had committed, I was immediately immersed in all the big and little things it takes to run a business.

It was sink or swim.

If I sunk, I’d be out some money and time and effort. I’d likely have to wander off and get a real job. But worse, I would have failed. And for some reason—deep within me—I really, REALLY didn’t want to fail at this.

I quickly learned the most important things I would ever need to know about business. Two words: Supply & Demand. (Well, two words and an ampersand.) In a free market, supply and demand dictate the price and marketability of all goods and services.

Any goods or services for which there is no demand have no value. Put any price you want on it. If there is zero demand, there are zero sales. If there is high demand for a good or service and the supply is low, the price will increase as competition to buy (and find and offer) increases.

I was very lucky. Maybe someone was watching over me.

“Ahem!”

Ah, my Book Muse! I’m glad she is here. I need some help getting this story off the ground.

“Good morning…ummm… are you ever tell me your name?”

“Rumplestiltskin. Yes, indeed you were very lucky. Luck and hard work are fundamental economic principles as well. Ye have a title at the top of this page. What has it to do with what you’ve written so far?”

“I’m laying the ground…”

“The groundwork. Aye, so I’ve heard many times before. And I’ve heard about yer pine shelves before as well.”

“Hey! Maybe I should write about all the bookcases I built. The measuring, staining, cutting, nailing…”

“Better change the title then. But if yer keeping this title, I suggest you get on with the boomin’ and bustin’ soon or ye’ll be borin’. I’m off.”

Ok. Ok. So the store opened. The rent was paid. Books were bought and sold. I soon learned what sold quickly and what seemed to never sell. I BEGAN learning that some books had more value in the market than others.

How? Numerous ways. In those days, I would often be visited by other, more experienced booksellers. Say a Civil War specialist like Dave Zullo would come in. Why would he pull certain books off my shelves and buy them at my price (less a small “Trade Discount”) and completely ignore others? He was one of the helpful ones. In the long run, his training taught me what to look for in Civil War books. It paid off for him as well. If I got anything really cool in, I would pick up the phone, a landline of course, and call him first.

Other specialist dealers were secretive and wouldn’t part with any of their arcane knowledge.

I attended many country and estate auctions in the early years as well. I would scan the classified ads in area newspapers, print versions of course, and try to discern if:

1. There were books.

2. There were a LOT of books.

3. If the books might be extraordinary.

This took a lot of “reading between the lines.” Auctioneer ads could be deceptive.

“Boxes of books”—might mean 3 boxes total.

“Old books”—could mean 30-year-old junk or books from the 18th and 19th centuries.

…And so on.

But if the ad said “Hundreds of Old books” and the rest of the ad made it clear there were lots of nice antiques in the estate as well the odds of the books being good increased.

It was a terrible waste of time to drive an hour away down narrow country roads and discover the books being auctioned were dreadful or for any other reason not worth the trip.

Auctioneers were generally not cooperative over the phone. And often they didn’t know if the books were good or not themselves.

Another torture would be if the auction company wouldn’t tell you when in the course of the day the books were going on the block. Even worse some wouldn’t sell the books all at one time. If they decided to spread them out you could end up standing around all day long—IF the books were even worth waiting for.

But at the big collectible book estate sales, you could learn a lot by seeing what the old pros were interested in and how high they’d run the price up on certain individual books or themed lots.

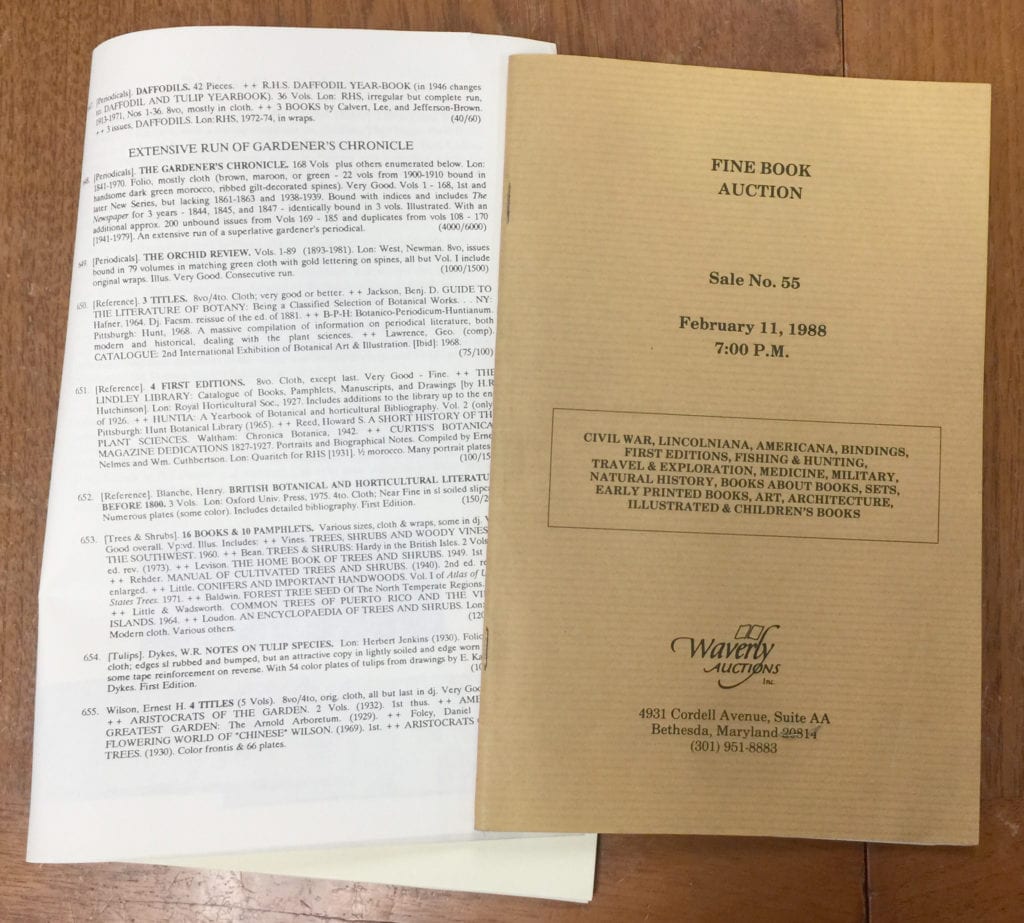

I also attended pure book auctions like Waverly in Bethesda, Maryland. They held monthly sales about 10 months of the year. Maybe 100 dealers, collectors and mysterious “phone buyers” would bid live on single books or small lots. Other buyers would have already left “mail bids.” Mail bids were forms a potential buyer would fill out indicating the maximum price he or she would offer on a numbered lot or lots. The auctioneer’s assistant would act as that buyers proxy bidding from his mailed in form until the lot sold or the maximum offer dollar amount was surpassed. After a little wine and cheese—the wine could do wonders at loosening bidders’ reserve (i.e. purse strings.) They would blow through 600-900 lots in an evening. Amazing! Each lot was carefully described in the catalog which they’d mailed to me weeks before. During the auction I would pencil in the hammer price next to each lot. Sometimes I would emphasize the selling price with an exclamation mark… or three or more… if something seemed to sell very high (or low.)

These auctions were as much a learning seminar for me as an opportunity to buy anything for the shop.

So, I began learning more and more about what sold and what didn’t. I also began learning what books had potentially high values.

Generally, back then the high values corresponded with age and subject matter. An 80-year-old title about Japanese swords could be worth a lot of money. A 10-year-old title on the same subject might sell for half its original retail price. The assumption was the older title was scarcer than the more recent. The more recent title was likely still “in print”—which meant you could still order a full price new copy from the publisher or any new bookstore. Old books on regional history could command a high price.

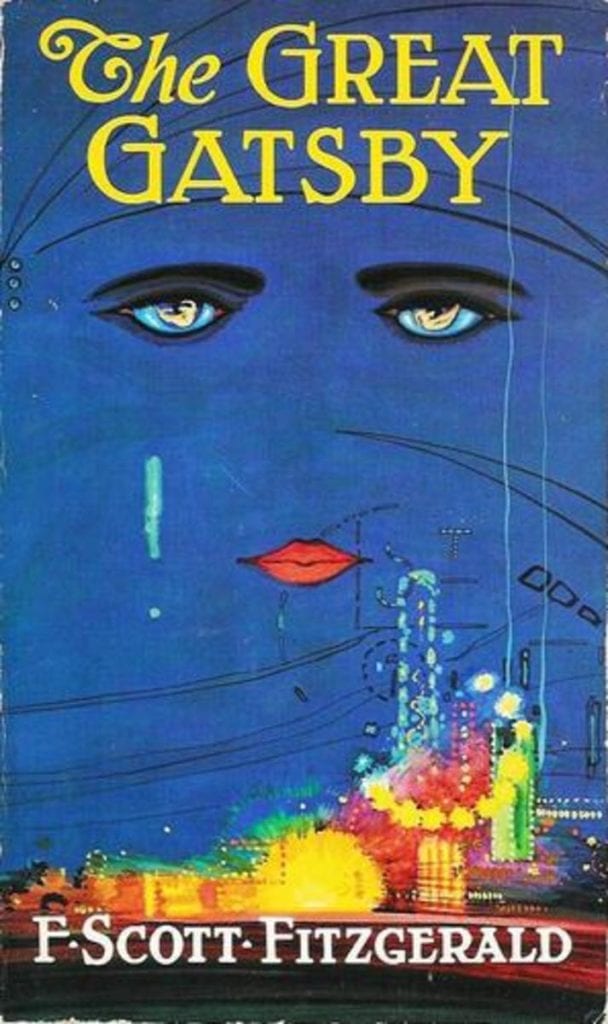

In the used book market, most modern fiction sold for a fraction of its original price—if it sold at all. But first editions of blue chip authors like Hemingway, F Scott Fitzgerald and William Faulkner could sell for hundreds of dollars. Their work had stood the test of time. It was actively and constantly being reprinted. The mysterious attraction book collectors have to “first editions” (is it because that is as close as you can get to the genius’ creative process short of a manuscript?) drove the prices up on those authors. The supply of nice copies was far exceeded by the demand for them.

It made sense.

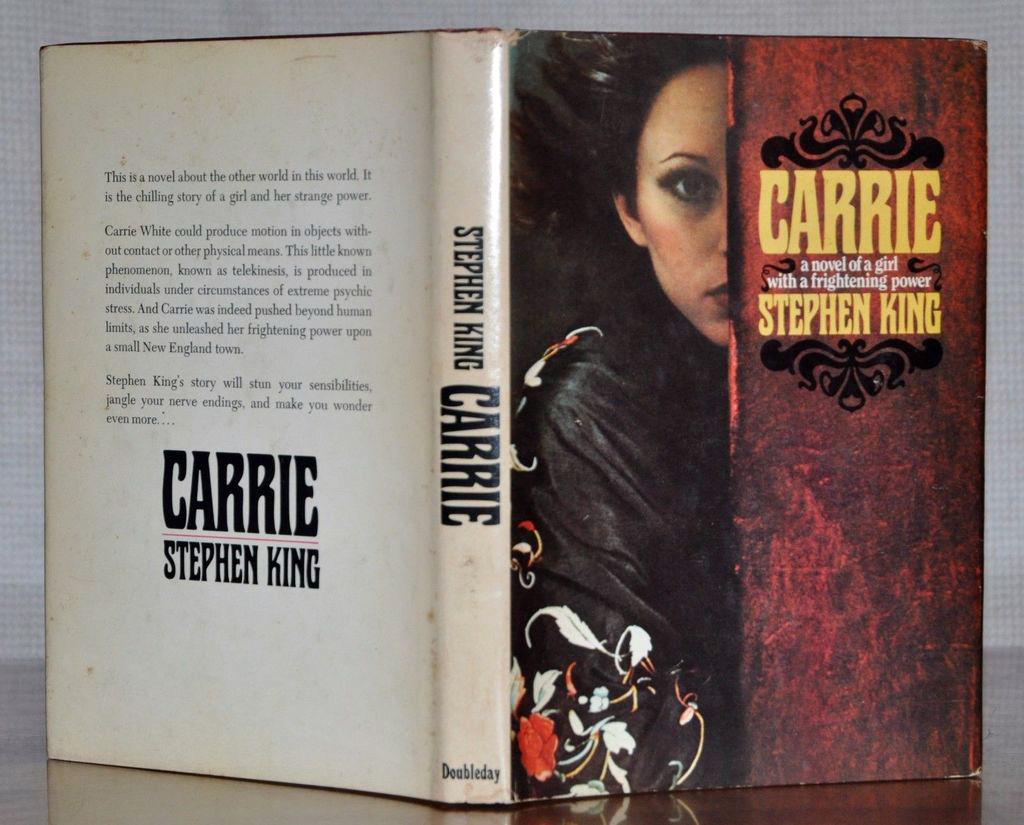

But then something kind of mysterious started happening the mid 1980s. Relatively young living authors’ works started becoming collectible. Stephen King’s Carrie was an early example in my recollection. It was published in 1974. It was King’s first book. Young people especially were rabid about his work. Each new book he published was an instant bestseller. People would flock to Waldens to get a copy of his newest book on its release date. And there were a LOT of new Stephen King books coming out all the time. His output was prodigious. I recall a 1987 Saturday Night Live skit about him. The character playing King is frenetically typing AS he is being interviewed—the joke being: he never stops writing.

See it here.

Suddenly, a first edition of Carrie in a dust jacket was a $100 book! That was odd, in retrospect, because according to Wikipedia 30,000 copies were printed. A respected ABAA bookseller states today on Via Libri that “13,000 copies sold.” It seemed so counterintuitive to me even then. The book was just a decade old. There should be lots of copies in the market. Other King first editions began to quickly rise in value as well. More recent titles like Cujo were suddenly $35 books. There was no reason to debate the merits of these prices. The customer is always right. Stephen King first editions were instant sellers if they were in good shape and had very good or better dust jackets.

Things then got odder and odder. I liked some modern authors like John Gardner (the American novelist) and John Fowles. In Allen and Pat Ahearns’ 1995 Book Collecting, they list the British first in dust jacket of Fowles’ first book The Collector as being at $35 retail in 1978. $650 in 1986. $750 in 1995.

BOOM!

I, along with any many other booksellers, began looking for RECENT books especially by certain authors. We were speculating a bit as to whether this book might go up in value as it went into later printings or disappeared out of print entirely.

Many booksellers would scan Remainder House’s newest catalogs in case a title by a hot author was dumped by a publisher. Speculators might buy 10, 20, 50 copies of a remaindered Jim Harrison title. You’d just have to hope all the copies you’d get would be firsts.

What caused these books to increase in price? Demand.

This period coincides with the booms in newly printed baseball cards and comic books as well. In hindsight, I believe some of the mania had to do with the boom in value of rare early baseball cards, comics and blue chip fiction authors. Unless quite wealthy, one couldn’t approach acquiring a Superman #1 or Honus Wagner baseball card or The Great Gatsby first edition. But you could get in on the ground floor of future collectibles by buying “instantly collectible” comics, cards and books.

Publishers began issuing signed limited editions of popular authors prior to the trade editions. They’d be limited to 250, 500, 1000, 1250 copies. Instant rarities!

At a certain point, things began getting absurd. When I came across a beautiful slipcased signed limited Danielle Steele novel, I knew something was wrong. But I didn’t know what it was.

Collecto ad absurdam.

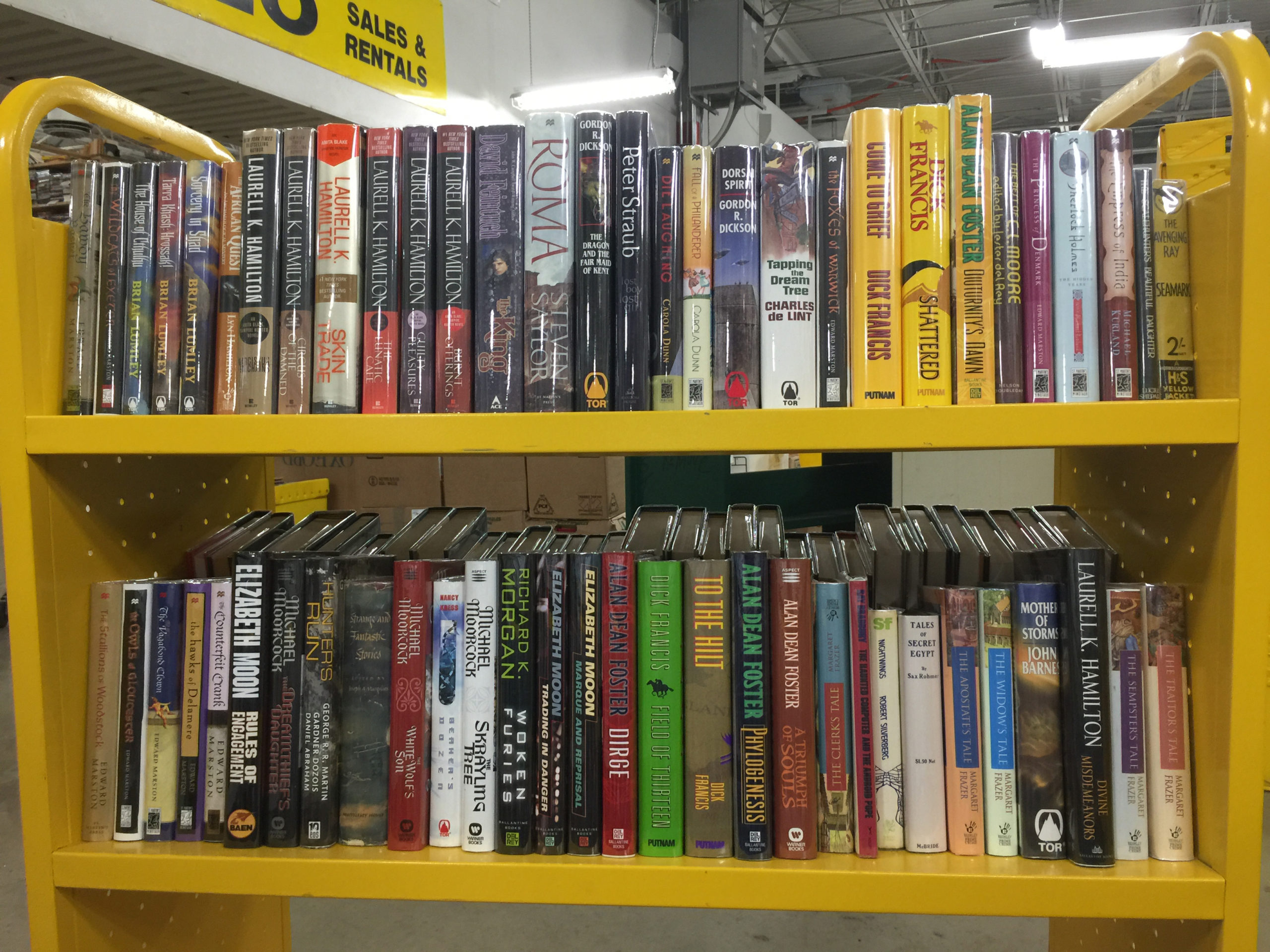

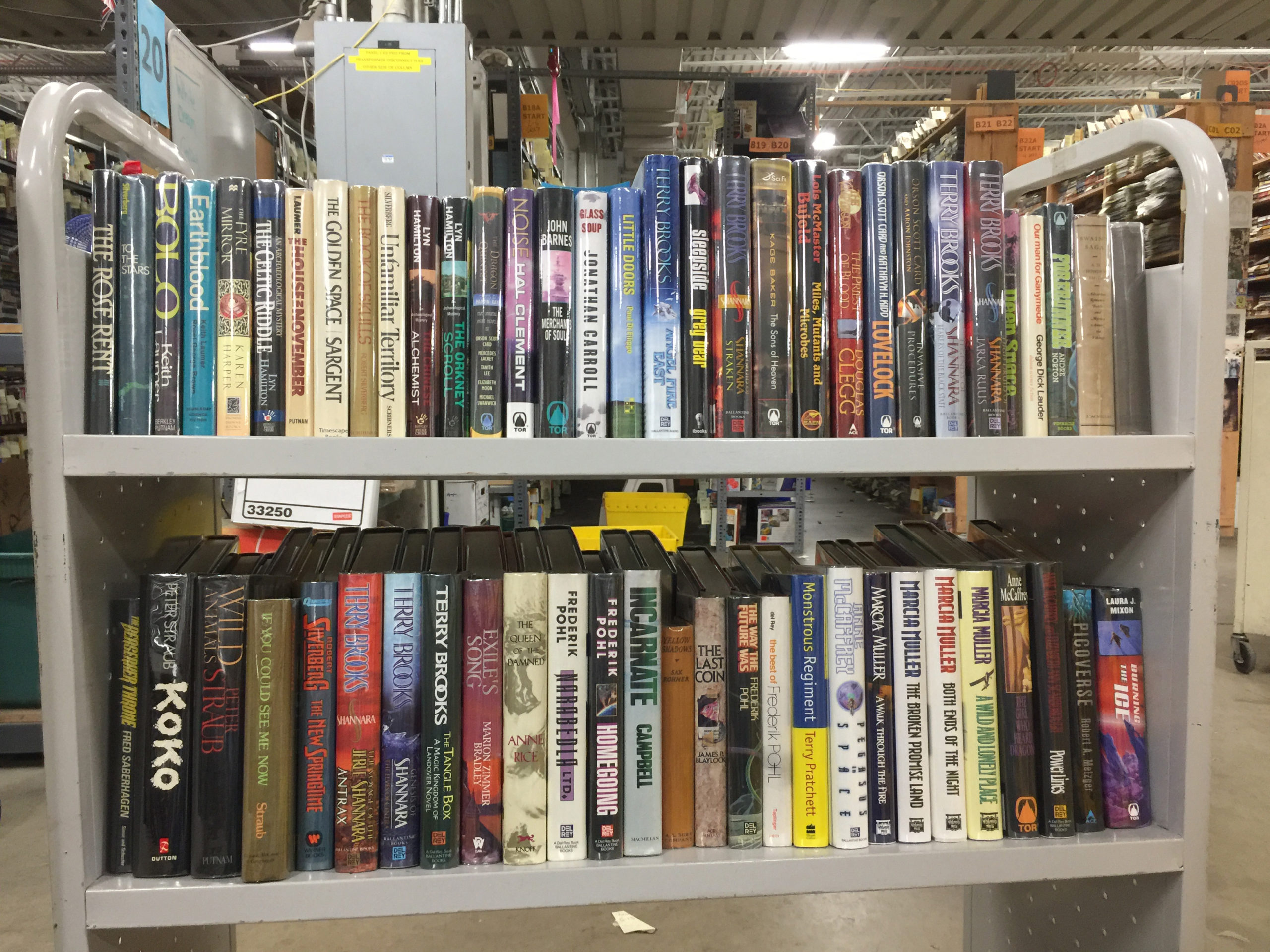

And the customers were demanding more. At a certain point, just about any remotely literary first edition as well as SciFi, Fantasy, Horror and Mystery first editions with great dust jackets became collectible AND collected. Just about anything in the above genres could be priced at $15, $25, $35 and up…

Many books were selling for more than their original retail price within a couple years. Sometimes within days.

Drums and flourishes:

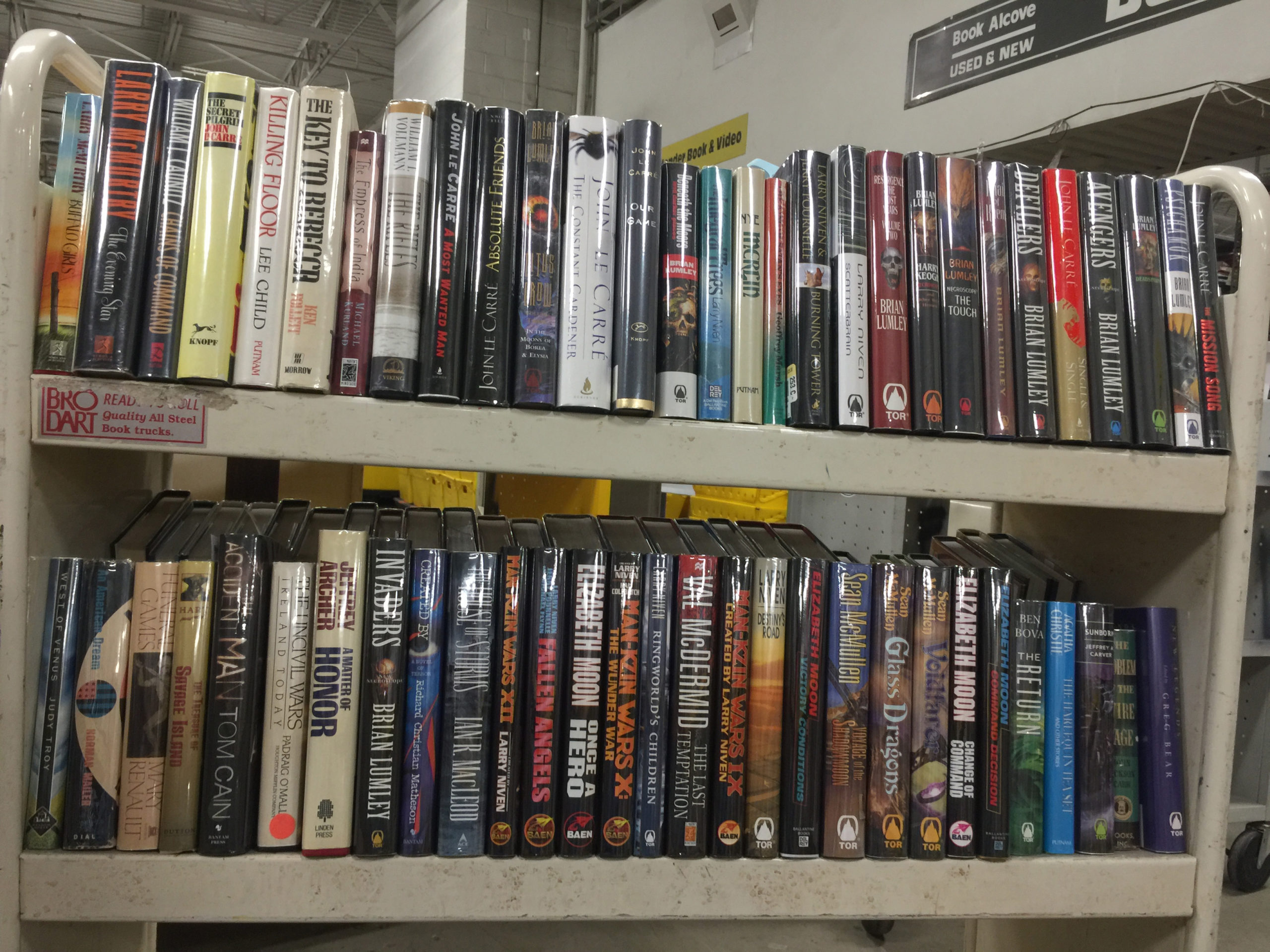

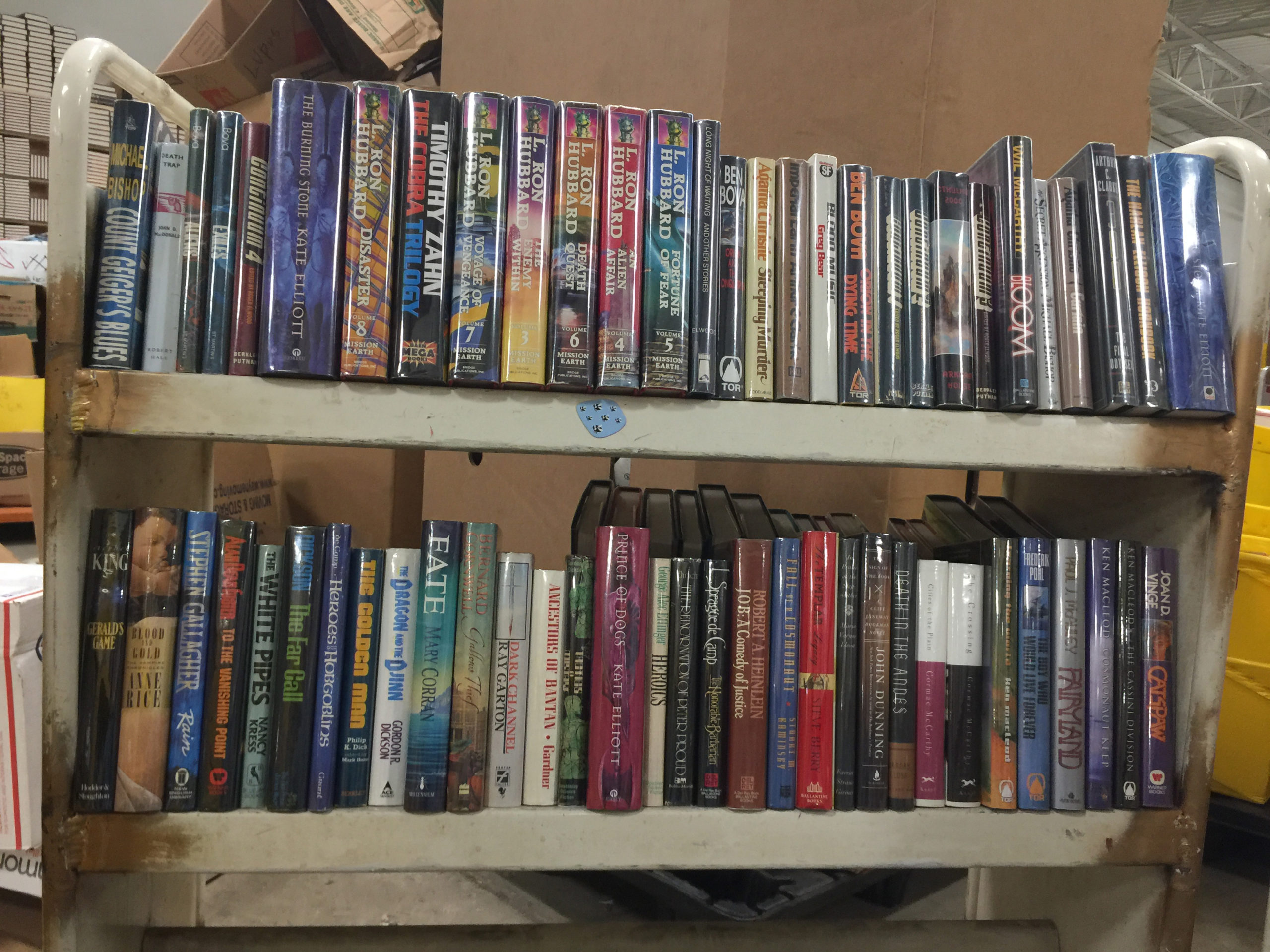

ENTER THE ERA OF THE BRODART!!

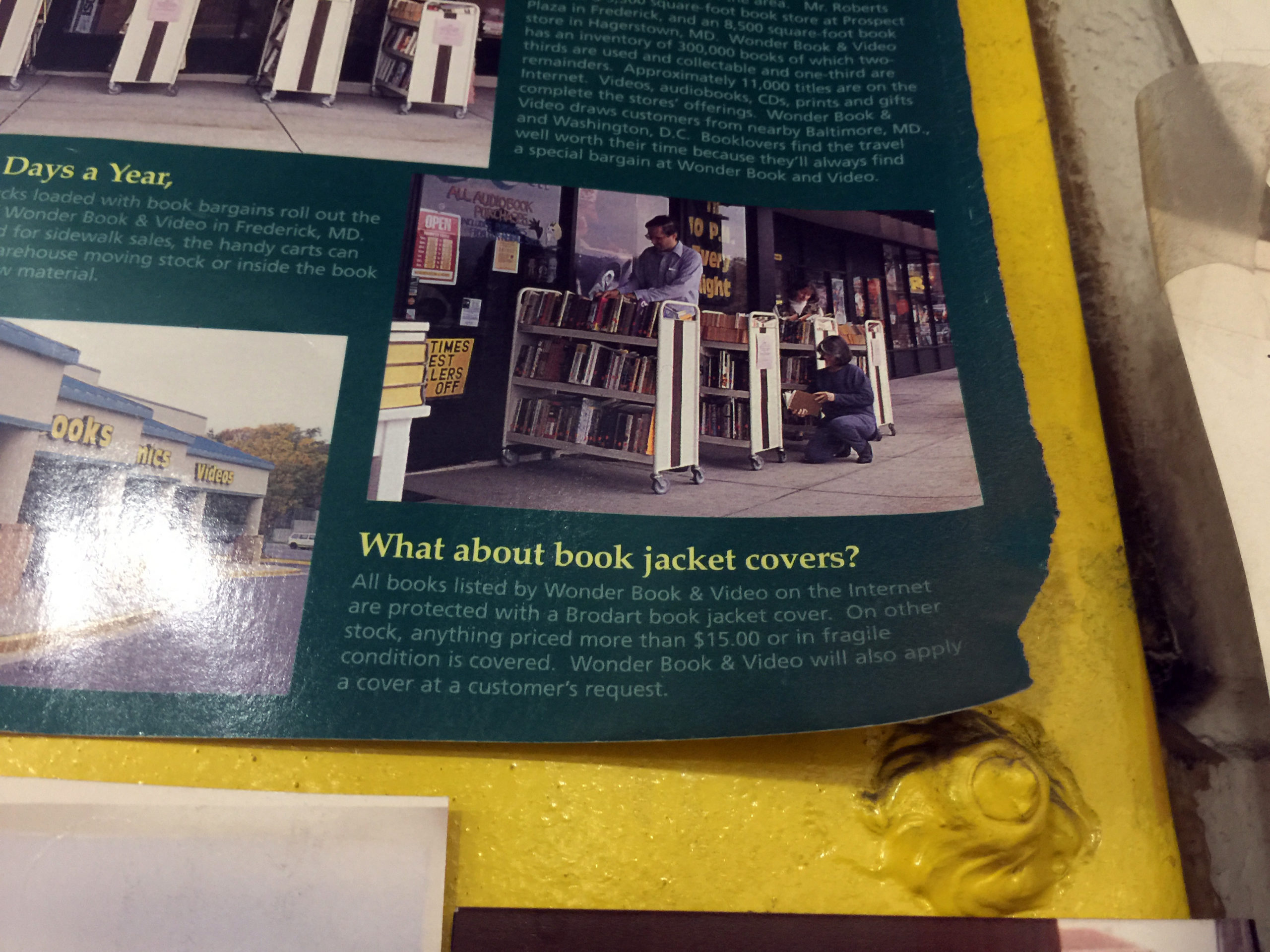

I can’t remember when I first put a Brodart book jacket protector on a dust jacket. In the early days, we would be quite selective. After all, they cost about 25 cents each then and took a minute or two to put on. Before long, however, we began wrapping just about every first edition’s dust jacket above a certain selling. Why? Paper dust jackets are quite easy to tear. A torn jacket meant the book was no longer in perfect condition. It could no longer command the “perfect” price.

Soon we were wrapping EVERY dust jacket on books we had on offer for $15 and up. We began ordering them in packs of 100. 100 8″, 300 10″, 100 12″… We began offering them to our customers. I think they sold for 49 cents. Customers would buy them for their own home libraries. Often a hundred at a time. Soon the orders we submitted to Brodart were in the thousands.

My Brodart in-house sales rep—I believe her name was Connie Walck—daughter of the famous publisher of fine books Hank Walck—called me one day and asked if she could come visit.

“Sure!” I wondered why but didn’t ask.

When she arrived, she had an assistant with her.

“I’m here to see if you need anything, of course. But why I am really here to find out about is what you are doing with all the dust jacket protectors you are buying. The higher ups noticed, and they are curious. Your single used bookstore is ordering as many as some library system clients we have.”

I took her to the fiction aisles and mystery and scif/fantasy aisles. I took her to our 50 or so glass cases which held our more valuable books which we felt should be keep under lock and key. So many books out there had the shiny glistening aura of a book whose jacket was being protected by Brodart’s mylar product.

“I’m selling a lot to customers as well—so they can protect their own books.”

She was still a little confused. Most of their products went libraries and schools. Bookstores would order occasional supplies and furniture.

She asked if she could take some pictures to maybe feature us in one of their catalogs. Her assistant began shooting various things around the store.

We made the back cover! That was likely the first “national ” coverage we had. It was kind of a big deal to me, anyway. Those big catalogs went to every school and library in the country—maybe beyond. They also went to many big bookstores and chains. This was well before most people ordered from online catalogs—if they existed!

Were we the Brodart Jacket Protector Kings? Maybe for bookstores. I’m sure many of the larger library systems wrapped far more books than we did. But wrap we did. And wrap and wrap and…

The boom was in full swing. Glistening books sold by the stack in the stores and at shows I would set up at.

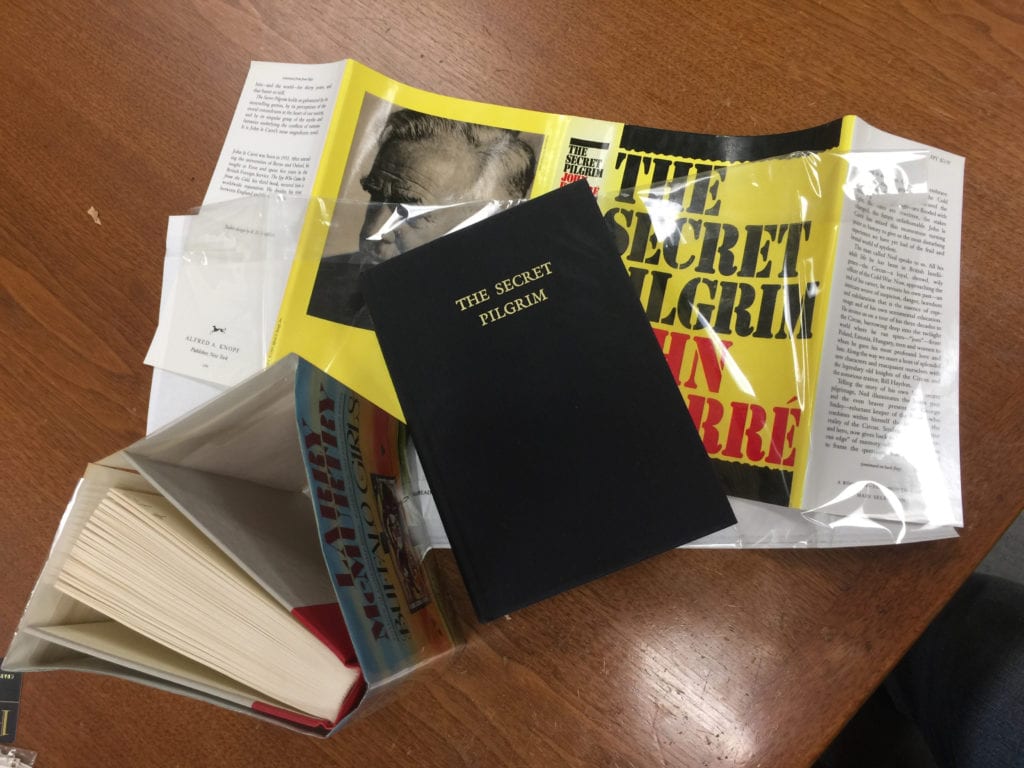

Then it was 1997 or maybe ’98. We had 3 stores by then. They were doing quite well. We were renting VHS tapes and selling compact discs. (LP vinyl record sales had crashed.) We were selling lots of books. The icing on the cake were the modern first editions now dubbed “Hyper-Modern” by…someone…selling for $15 and up and up and up…Some collectors bought modern firsts like baseball card collectors. They’d try to get every book published by a living author—including the British editions. The REAL hardcore ones went after other international firsts. Some collected magazine appearances. There became a brief hot market in proofs and galleys.*

* Proofs = Precede the published book. The normal course of events would be galley proof, uncorrected bound proof and advance reading copy bound in paperwraps. / Galleys = Sometimes called “galley proofs” or “loose galleys” to distinguish them from bound galleys. Long sheets of paper bearing the first trial impression of the type. AbeBooks

I remember attending the national new book conventions held every year around Memorial Day (ABA—then BEA.) I would search up every free uncorrected proof offered to me. They were free! I recall the excitement when Putnam Publishing handed me a new Tom Clancy proof. I bumped into a friend and said: “They’re handing out 50 dollar bills over there!”

The market for proofs quickly died. Now we pulp most of them. But some are still quite valuable. Like these JK Rowlings for instance.

What could go wrong?

The book Cold Mountain was released in 1997. It was an instant hit. It was to win the National Book Award. Any new publication that won any prestigious award would immediately become an even more expensive collectible hyper-modern.

I’m operating on memory in the following, but I vividly recall attending the Florida Antiquarian Book Fair. It was likely March 1997 or ’98. (I believe I set up a booth at every FABA Book Fair from 1982-1999.) I had a copy of Frazier’s book in my booth for $35. I thought that was pretty aggressive price for a book that had just been released. It sold immediately to another dealer. This dealer naturally raised its price to make a profit on his investment. Someone bought that copy, and it appeared in another booth. A little buzz began amongst the dealers. “What’s going on?” By the end of setup the book, my former copy, was resting on the display table of one the top Modern Firsts booksellers in the country. He was known for his aggressive pricing. He helped all of us with that strategy. His raised prices raised all our prices as well. Most important, he SOLD books at the new high market value. Cold Mountain had in a matter of hours become a $350.00 “investment”! I guess because it was the only copy there. “Supply.”

BOOM!

1997 was also the year that I became convinced to begin selling books on the “Computer.” [read about it here] I didn’t understand the World Wide Web. I was a bit of a technophobe. But most of all I wondered: “Why bother!” We were doing great with videotapes and CDs, and books were flying in and flying out at great prices. Booksellers and collectors would often make trips to our Frederick store and buy heavily. I LOVED seeing other book dealers come in. I never understood any other book dealer that would refuse or reluctantly serve a competing dealer. Why? They often spent hundreds or thousands of dollars! Most books were not irreplaceable. Any gaps they made in the shelves would soon fill in. So Clark Kline—the visionary—then and still—had finally convinced me to list some books on the “Internet.” My brother, Tony Roberts PhD, also a visionary and tech embracer, had also been bugging me to do this. I surrendered to their “folly” and “waste of time.” We listed about 40 titles I’d selected from our open stock. All we had was open stock. I didn’t do any catalogs. I rarely listed books for sale in the legendary and now defunct AB Bookman for mail order.

To me shipping books in the mail was a P.I.A.

They set to cataloging a little lot of books on the big PC in the back room. I didn’t pay much attention to that operation. It was over my head. And why bother. I’m sure there were lots of “http”s and “www”s and backslashes and forward slashes and who knows what else.

It was done, and we all went home. We had two-score books offered supposedly “world wide” on the computer in the back room.

The next morning when I went in, Clark announced: “We sold our first book!”

“Cool! Which one?”

This one:

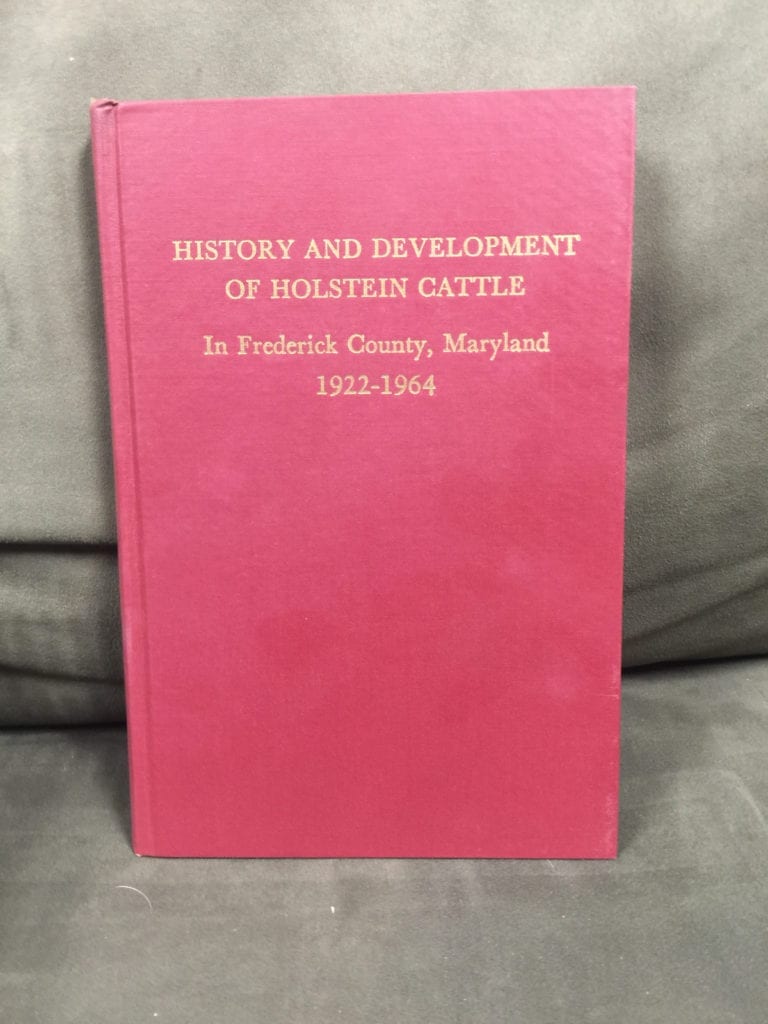

Remsberg, John Homer

History and Development of Holstein Cattle in Frederick County, Maryland.

Printed by the Vermont Printing Company, Brattlenoro, VT, 1946. 1st edition. 12mo Hardcover 110 pgs. B/W photographs.

“Wow! I’ve never sold one of those in the store. I’ve had that copy for years!”

It is a slim hardcover with a blank spine. It is virtually invisible on the shelf.

Clark replied: “Yeah, a guy in England bought it.”

“!!!!!” I thought

When I came out of shock, the proverbial light went on above my head. We were global now! A local book about dairy cattle which was unsaleable here in its hometown would soon be on its way across the ocean.

“Let’s put some more books on the World Wide Web,” I suggested humbly.

Fortunate decision.

So the internet became a nice sideline for selling exotic niche books. Meanwhile, the stores continued to chug a long.

I recall vividly a regular customer who was a Stephen King collector. He was a friendly nice guy and had bought a lot of signed books from me. Maybe around 1999 he came in and I pointed to a large plastic bag pinned to the wall behind me.

“What do you think of this?”

It was the 1983 King/Bernie Wrightson portfolio of drawings for the Cycle of the Werewolf. It was a limited edition of 350 and was signed by both.

“I’ve got 750 on it but I could give you a little discount if you’re interested.” I was sure he would be.

“I got one a couple weeks ago on the computer for $300.”

“Impossible,” I thought. “It’s a $700 book. I’d pay more than 300 for it.”

“Oh, ok.”

That was another epiphany of sorts.

Soon there after began the deluge. The Bust.

Instead of professional booksellers listing just unusual or expensive books online, hundreds of thousands of people became booksellers in their basements and garages. They began filling the early selling platforms like ABE and Bibliofind with their own books and books they’d get at yard sales. Suddenly, people with no previous book experience were global book experts. If they needed any data for a book they had, they could “borrow” it from legitimate booksellers. They could simply cut and paste the arcane information from an expert’s listing. Since they had no overhead and often little or no cost for the books in their inventory, they would naturally list their copy for a few dollars less than the lowest matching title. Then someone would undercut them. And so on…

In the stores, things were still going well. But I noticed things that had been great sellers were now multiplying on the shelves. How could we have 5 Cujo first editions? It had been a $35 book. These were marked down to $15. When we looked online, there 40 or 50 copies around $5.

Amazon entered the fray, and before too long many people were listing books there for pennies.

BUST!

I found a pretty fascinating article online by Ken Lopez. He was and is one the very best booksellers in world. This article was written in 1999 and provides some amazing data at the cusp of the internet driven revolution in bookselling. For within 10 years of this article’s publication, I’d estimate 90% of the brick and mortar independent book stores in the United States were closed. So, Ken’s 1999 story must be looked at in the context of the time it was written. Here is some of his take on hyper-moderns at that time in history:

First editions of these books began commanding higher and higher prices, as the small supply could not match the demand until the book’s price rose so high that some of the demand slacked off. And after a few years of that, there came to be a certain amount of speculation, as people tried to pick which books would be the ones that would be in demand, and buy them while they were still available. Now there’s even a “tip sheet” for collecting hyper-modern books called Bookline, and one for collecting hyper-modern mysteries, published in the San Francisco Bay Area, and giving information about upcoming book tours, “pick hits” of the new books being published, reviews, and occasional but ongoing tracking of the titles they’ve picked in the past.

I mention hyper-modern collecting for two reasons: because it’s become an important element of the trade in modern first editions (although, like “high spot collecting,” it doesn’t dominate the market nearly as much as some critics of the modern book trade suggest), and also because the speculative edge to that market, which drove prices of such books as A is for Alibi into the four-figure range, was an indirect contributor to the rise in prices of more solidly established modern high spots.

The rest of the article is here. It merits reading for some of it was prescient. You can also see that none of us knew what was coming with this new fangled “Internet” thingy.

So what is (or was) a hyper-modern? Biblio offers this definition:

A very recently published book where the market price has increased quickly due to book collectors speculating on the future value.

And from the perspective of hindsight, what really happened to the market? A lot of things culturally, technologically, financially, “mail orderly”…but in my opinion, much of the bust was caused by supply and demand. You can also include greed and speculation. Buyers felt the prices would continue going up. Booksellers simply offered books at the current market values.

The internet selling platforms like ABE.com could graphically show there was a huge supply of Cujo first editions. Makes sense in retrospect. 150,000 were published. Nowadays I’m not sure we’d even look inside a Cujo to ascertain whether it was a first or not—unless it was in exceptionally pristine condition.

What happened to Cold Mountain? Maybe it is a $20 book now. But you could likely find it cheaper with a little patience.

The Collector—a 1963 title—is perhaps a $100 book now.

Carrie? That seems to have held its value. $700-$800. Maybe there are 15,000 Stephen King collectors? Maybe the publisher’s claim of a 30,000 copy initial print was a little hyperbolic? Dunno.

There is a brighter side to the internet as well. During the “Wild West” times of crashing prices and hundreds of listings for common books, it also became apparent that some books were actually quite scarce. You would go looking for a first edition of book “XYZ” to see how many were out there and what they were selling for and your screen would read:

“No results.”

Hmmm…what do you do then?

Sky’s the limit?

Supply and demand can still work upwardly.

It’s not all bust and gloom for modern firsts. A low internet population of some books can also prove a title is generally scare—or even rare.

Here’s some data supplied to me by Allen Ahearn. I’ve tweaked some his numbers. The auctions prices he supplied me with can often be sub-retail. So, I’m “speculating” a little on what the retail price for a first edition of The Great Gatsby in dust jacket would retail for the years listed below:

- 1963 = $300?

- 1973 = $500?

- 1982 = $6,000?

- 1991 = $14,300

- 1993 = $19,800

- 1996 = $27,600

- 2002 = $75,000

- 2011 = $250,000

I don’t see any listed out there now at any price. So, what would a great copy of this book in a nice original jacket list for in 2018? I dunno. Try a crystal ball…

And what do we do with the hyper-moderns that come in nowadays? Some still have value to readers or collectors. Some there are just too many copies of in the open market—we will get 100 nice copies of megasellers like The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown for every one we could sell to a reader for a few dollars.. Many of those go to our Books By the Foot division. The alternative would be to pulp them. They are just too beautiful for that.

Will there be future book boom / busts?

I dunno.

But I assure you we are always looking—hoping to spot the next trend—the next market—up or down. Early!

I need to wrap now for today’s deadline. I’m heading to NYC for the Fancy Food and Drink Convention. I’m looking for exotic things to offer customers in our brick and mortar stores to eat and drink. I’m also planning to look at some of the wonders in the Morgan Library and perhaps the Cloisters and …

I’m sure there will be some errors and omissions in this. It is a big convoluted story. Please email me or leave comments and we will edit and correct on Monday as needed.

Chuck, Thanks for taking up the topic of “hyper-moderns.” Although your example of King’s “Carrie,” with a 30K first printing seems like a counter example, I’d suggest the reason collectors want first printings is that they are almost always conservative, and scarcity = $$.

In the era of “Carrie,” first printings of first novels were most often in the 5K -8K range, at least at the major houses. First printings at smaller houses and university presses might be 2K – 5K.

That first printing for “Carrie” suggests to me that the publishing house (Doubleday) really decided to make a “statement” about their discovery of this new author. By the mid -80’s King had moved to Viking, where I sold “It,” “Misery,” and some others. I remember those “announced” first printings as being in the 100K vicinity. Of course, what the house announced at sell-in was often not was actually ordered from the printer. In King’s case the “announced” first printing might actually have been exceeded, but for most authors the “announced” number was hyperbole.

Cool! I have things to add Monday. Carrie has apparently held its value $700-800. That’s odd if there were that many copies printed and collecting started so early. There should be a lot of copies out there – and more appearing as original owners unload their books. Something doesn’t add up imho.

The collectors of the hyper moderns in 80s and 90s are at the point of downsizing so more and more Brodarted hardcovers are appearing.

I remember at the ABA/BEA being excited w some of the Proofs being given away. Young and poor I told a remainder house friend “They’re giving away 50 dollars bills at …” i.e. Tom Clancy proofs – now worthless.

Also, booksellers got excited when Jim Harrison etc appeared in remainder catalogs … of course, you didn’t know if what you ordered would be firsts. Some would visit the remainder warehouses and root through the stock. Remainder houses stopped that quickly as so many of their new pristine copies were being handled – their copyright pages looked at hoping for “1234567890”

A few significant jackets can increase the value of a book tremendously. In his (rather over-the-top) book, “Book Jackets: Their History, Forms, and Use,” Thomas Tanselle reports an example where an unjacketed Great Gatsby went for $3,660 at auction but a copy in a “slightly frayed” jacket went for $182,000 at the same auction. There probably are other factors involved there, but apparently the famous cover can drive up the price of Gatsby by a factor of 3 to 5.