Godrevy Lighthouse, the edifice in Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse.

Gray green seas smash

onto black stone cliffs

The waves strike and explode

into white sea spray

and glowing silvery foam

Cornwall, where magic rises from the earth.

Where a day in the sea salt air saps your core. Perhaps it is the constant flooding of glorious oxygen filling your lungs.

It is a satisfied weariness.

Content to be powerless in the presence of such strength.

Nature’s clashes are the way of life in this land of sea and stone.

No.

Those words don’t capture it.

New York City used to have power and confidence rise from its sidewalks and into you as you walked. Much of that is spoiled now. There’s more fear and depression and hustle. How could something like that change?

Cornwall can’t change. At least for a hundred or five hundred years. There is too much of it.

I brought a copy of Daphne du Maurier’s Vanishing Cornwall with me. (2007. Virago Press. Reprinted from the first edition of 1967. Fine in a fine dust jacket. Illustrated in color and black and white.) From her descriptions of 55 years ago—and going back to ancient times—my impression is little has changed on the landscape. Some more roads. Some houses. Some more technology. But the towns and cities are like picture postcards frozen in time. The countryside is vast. Much of it is unbuildable, and, so, will remain unchanged in perpetuity. Wikipedia states it is one of England’s larger counties with one of its smaller populations.

Long, long ago, the ancient kingdom of Lyonesse was between current Cornwall and the Islands of Scilly. It was home to King Arthur and Tristan and other Knights of the Roundtable. It was afflicted with some cataclysm. Perhaps in November 1099. Perhaps long before. The knights were able to ride out of the kingdom on white horses before the kingdom quickly sunk.

That was a big change. But it adds to the eternal magic of the place.

It was a great week.

I’m wrapping this up on Thursday evening. Friday, we get picked up from the hotel in St Ives. Duncan will drive us to Heathrow with a few stops along the way. We will spend the night at Heathrow and fly home on Saturday.

My son, Chuck, is out at the Minack Theatre. It looks stunning. I was too beat to go. We had driven so much today—every day—I just wanted to put my feet up and enjoy this room with a view at the hotel Pedn Olva.

That lighthouse aglow reflecting the sunset in the distance is the Virginia Woolf’s—as in To the Lighthouse.

We got so much done. It was a bit frenetic. But that was my choice. I’d rather experience ten different things than a leisurely three. Somehow, I feel I “own” something once I have seen it. It becomes a part of me. And with the internet, it is easy to “revisit” if you wish to go deeper.

Today began with a race to the south coast and Mount Saint Michael. It mimics Mont St Michel. It was built by the same order of monks. We had checked at the end of yesterday, and the ferries were running from 9:30 on. We timed it to arrive for the 9:30 ferry.

“The sign says no ferries today.”

We rushed up to the deepwater ferry launch, anyway. No ferry.

The sign in the beach sand had read there was no walking across the causeway this time of year either. We looked, and a few people were inching along the stone walkway to the island as the tide ebbed. Soon, the entire walkway was exposed. A few people walked across and got their feet wet as low waves washed over. More people joined the crowd. My son checked the phone and said it reported the causeway would be open at 9:55. Sure enough, the water stopped slopping over at that very minutes. Some limpets clung to the stones as we walked across.

It was a pretty amazing journey with all that beauty above and around you.

The legend goes that the giant Cormoran built Saint Michael’s Mount as his home and base to raid cattle and children from mainland communities. (Cormoran was later killed by a boy named Jack. a.k.a. Jack the Giant Killer.)

We climbed to the castle and walked through. From the parapet, you could see the Land’s End peninsula to the west and the Lizard peninsula to the east.

Beautiful.

From there, we headed west along the coast. The first stop was Mousehole—pronounced “moe zell.” Perhaps it was named for the narrow passage in the huge seawall into the safe harbor. Duncan knows every nook and cranny in Cornwall. He led us down an alley to the cottage of Dolly Pentreath—”one of the last speakers of the Cornish language as her native tongue.” She died in 1777. It seems counterintuitive that the language began to die out so long ago. I don’t know if politics was involved. Conquerors often try to cancel culture as a first step toward assimilation. I know the Irish language is very strong. In some parts of Ireland, it is the primary language. Welsh is strong. I think it is mandatory to teach it in schools. I’m not sure about Scottish Gaelic. I’m sure Breton is likely extinct. Certainly that lost bastion of Celtic culture, Galicia, in northwestern Spain is long gone. All the Celts kept getting pushed west. Until there was no further west to go. Now, Duncan told us, there are only 500 or so Cornish speakers left. Though many signs are bilingual—especially in the west. The most Cornish language remains in place names and on buildings, restaurants and products seeking to capture some of the magic of the mysterious long ago.

I went upstairs to the restaurant to have a couple of beers and some food. In England, you typically order at the bar and pay right away. I’m so spaced out that I squirted a little ketchup on my gnocchi instead of the triple fried chips. Interesting…

I’m reading what Du Maurier wrote about searching for Arthurian sites in the 40s through the 60s with her husband. They counted on place names that might connect to historical incidents or names. Avalled could have been Avalon… Then they would start digging. Kind of fanciful. But it reads like they both had a lot of fun. I’m glad I brought that book along. It was a serendipitous find, as are most find in a used bookstore… or warehouse.

From Mousehole, we continued west. We meandered back down to the sea at Lamorna, where a mermaid is said to dwell. There are so many inlets with cliffs towering above each side and small sand beaches pouring out to sea.

“Well, you’ve seen enough beaches, haven’t you?”

On to a stone ring in a pasture demised by rock walls and barbed wire. It was a brilliant blue-skied day. All the distant haze had burned off. An older couple was lying in the grass just inside of the far side of the ring. Were they simply sunning themselves? I thought perhaps they were absorbing the special aura inside the circle. Cosmic rays or whatever. This circle is named the Merry Maidens. The legend goes that the girls had skipped church to go dance in the field. The devil spotted from the top of his hill (Devil’s Tor) and turned them to stone.

We pushed on to Land’s End. At the end of the peninsula, sheer cliffs drop to the sea. There’s an outcropping of jagged rocks a couple miles out with a lighthouse to guide ships away from death. Then… nothing but the Scilly Isles 28 miles out. A signpost has “New York 3147” painted on a board pointing to the west. There was another stone ring by the sign.

“No one seems to know about it.” Indeed, Duncan found us many intriguing places far off the beaten tracks.

Then a complex barrow grave where we stopped and ate pasties we’d gotten at a butcher shop in St Just. Duncan was right; they were the best in Cornwall.

The landscape out here is dotted with many tall brick Victorian-era smokestacks and decaying stone factory buildings. They’d been mining tin along here since they traded with the Phoenicians and perhaps before.

“They mined under the sea—up to a mile out.”

All that has healed over. The manmade structures are monuments to an incredibly hard life on the edge of the world and under it.

“All right. Let’s go stone hunting.”

Duncan took us out to remote farm fields where some of the best Stone Age monuments I’ve ever seen stood.

The ring at Men A Tor may have been for fertility. We passed a young woman walking the mile or so back to the road. She had a bag clutched to her and looked a bit sheepish as we passed.

Was she there for fertility or witchery or worship?

I noticed in the many stone walls demising farm fields there were large stones set in that had clearly been dressed. There must have been a complex of standing stones here. Sometime long after their magic had weakened, farmers must have harvested the big shaped stones to clear their fields and build their walls. The former monuments clearly stand out amongst the run of random rocks and boulders.

Maybe the magic was not completely gone.

“That farm over there just won’t sell. They say it’s haunted.”

Indeed, just off the lane we were walking down to return to the car, there was a nice complex of a stone farmhouse and outbuildings.

“That could be worth millions in the market today.”

I don’t know if I’d live up here on constantly windswept fields, the ocean in the distance and the spirits of earth worship saturated in the ground everywhere. I wouldn’t live long, I think. Likely madness would take me before long.

From there, he drove through maze-like routes, mostly on single-lane roads with hedgerows high and close on either side. Behind the thin layer of vegetation (often closely shaved gorse abloom in golden yellow) are high walls of thin stone. Duncan said tests show some are thousands of years old. Woe be to any rear-view mirror that brushes the edge. One year on a golf trip, we found that out, and the little car was returned with a mirror hanging down the side door by a couple wires. I guess the walls keep the winds off the road and give the farmers every inch of their field. They also mean the roads can’t be widened.

“Sometimes they move the walls back…”

Dolmens, quoits, menhirs, village complexes, fogous… it was amazing. My kind of stuff. In abundance.

We headed back. Duncan pulled off a few more times for interesting sights.

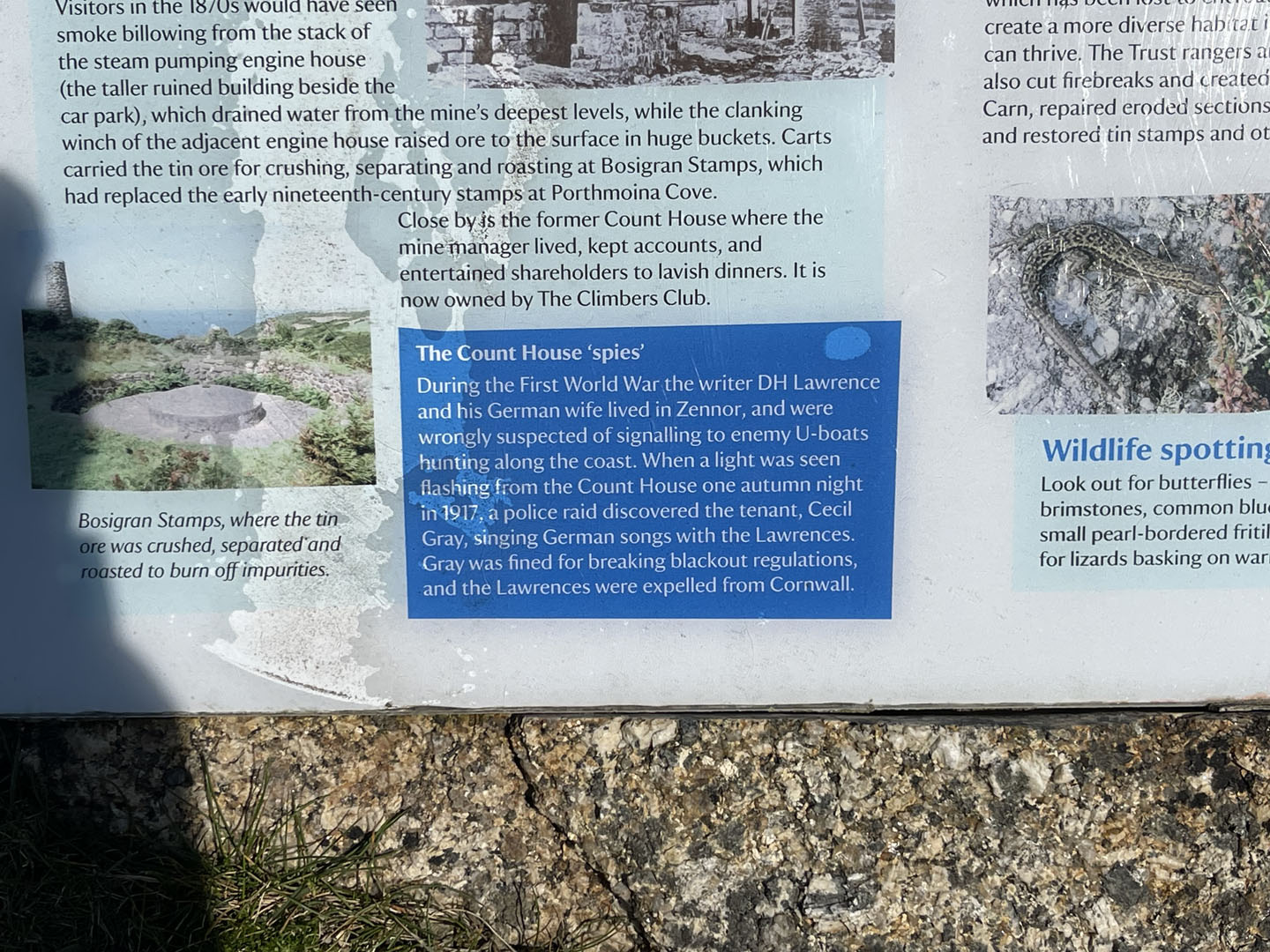

“D.H. Lawrence visited here with his German wife during the war. Someone overheard German singing, and the police were called. It was thought they may have been signaling U Boats. The Lawrences were expelled.”

It is Friday morning. Duncan is driving us up to Heathrow. There will be a few stops on the way. I’ve got to wrap this story up on the fly.

Back to Wednesday morning.

Duncan, our Cornish guide with Tour Cornwall, picked us up in Padstow. We had three nights in that seaside town. The estuary it rises above has many sandbars. The largest is called the Doom Bar. I’ve had Doom Bar beers and ales before. Most memorably in the 16th-century inn that Cap, Jim, Bob and I stayed at in Scotland in the fall of 2019. Little did we suspect that would be our last golf foursome together. We’d played at St Andrews and then moved below the Firth of Forth. The inn was in Aberlady or Gullane. The little bar cozied near the foot of the crooked steps. It was woody and warm and close. They had Doom Bar on tap. Was it a cask ale there? I think so. In England, that’s what I seek out. One night after a long, long walk over green rises and falls on the links by the shores of the Firth, the other three foursomes we were traveling with joined us and played a stupid golf game the innkeeper tempted us into. Whoever was “up” would climb atop a barstool and stand on its precarious, cushioned seat. (Really!) He’d be handed a putter. A ball would be set on the next barstool. The golfer, standing four feet above the floor, would attempt to “putt” the ball down to and across the floor. A wooden contraption, a kind of teeter-totter, was the target. If you hit your ball true and at the perfect pace, it would go up the wood and across the fulcrum. Up, up slowing til the teeter was overbalanced, and it would totter down, your ball rolling slowly out the other side for a kind of hole in one. Too slow, you roll backward. Too fast, and you go flying. Nobody “won” despite numerous attempts. Nor did anyone break a leg, which I suspected would be my doom if I did such a foolish thing. I, instead, recorded videos of the stunt while sipping a Doom Bar and wondering at the youthful exuberance of my companions, some of whom were in their 70s even back then.

Duncan is whipping along the one-lane roads which are the dominant pathways in much of the country. At least out in the country where we wanted to be taken to places of interest to us.

“You can tell a good Cornish driver by their skill at backing up.”

About a dozen times a day, we have found ourselves stymied by an oncoming vehicle. The roads are often not much wider than the width of one vehicle. Somehow, a nonverbal agreement was made as to whom would back up until the road widened enough so the other could pass by.

The first stop was a mining pit amphitheater where John Wesley preached a number of times between the 1760s and the 1780s. Gwennap Pit.

Let your light shine to all… miss no opportunity to do good.

John Wesley

One sermon attracted 32,000 attendees here. The pit comfortably accommodates only about 2,000.

We get a lot of books by and about Wesley. Most are quite old, but I think he is being sought again nowadays by people looking for something to hold on to. I was raised Methodist but protested enough, so my dad stopped making me go to church by the time I was 12 or 13. My “rock and roll” brother, Jim, spent the last few years of his life studying Methodist and Bible gospel. He was proud of his pins of achievement and hung them on a piece of leather hanging on his wall.

There are many Methodist churches in Cornwall. Most are severe buildings. Unornamented. No steeples or towers. A lot are being converted to dwellings. Duncan said he looked into buying a couple, but they had covenants that must be adhered to. No drinking, for example.

Whipping around the roads is the only way to get anywhere. Like Ireland, a Cornwall country mile is the equivalent of maybe four US miles. But that is what we wanted. A whirlwind. And Duncan can drive. It is like an amusement park ride sometimes. But we are packing in a lot of sights each day.

A normal person wouldn’t tour so frenetically.

From there, we crossed the peninsula to Trebah Garden. We’ve been to a number of grand gardens. They are associated with country houses. Usually. Some of the houses have been pulled down. Others converted to condos.

A remarkable one was the Lost Gardens of Heligan. These are spectacular. They had “gone to sleep”* in World War One when the 20 gardeners went to war and never returned. The gardens were abandoned (slept) for 80 years until a visionary stumbled upon them, looking for land to buy for pigs. They were vastly overgrown. Now they are restored.

* “Gone to sleep” is a Cornish euphemism for dying. A gravestone may read:

Mary Roberts

Went to Sleep

April 20, 1898

Heligan has been excavated over the last 25 years. They’ve attempted to bring back all its former features using the same plants that were cultivated before it slept.

The kitchen gardens were evocative. The gardeners had scratched their names on the wall of the “thunder box” (toilet), perhaps predicting they’d never return.

All the gardens we visited were a high point. So many things were in bloom. It tested my memory from the days when I made formal gardens and had hundreds of varieties. A couple things still stump me. I’ll wake in the middle of some night with an epiphany when some locked door in my brain creaks open. “That was a…”

Cornwall has a nearly subtropical climate despite the cold and windy conditions. Palm trees… It is cool and wet much of the year. Often cold but never freezing.

Grand gardens were a status symbol for squires and lords to have on their sprawling estates. They would try to outdo one another, sending plant hunters all over the world to bring back exotic discoveries.

It was a perfect time to visit the gardens. Rhododendrons as big as trees bloomed in electric colors, as did azaleas and camellias.

Gunnera, a giant form of rhubarb, grows here in a “forest” in which one could lose oneself.

The garden path leads down to the beach on the Helford River close to its mouth on the Atlantic. Here, many American landing craft were staged for the crossing to the beaches of Normandy for D-Day.

Since these gardens can be over 200 years old, some of the trees are enormous.

From there, we were headed south and west. We passed through the Cold War area of Goonhilly where huge early 1960s satellite dishes still stand. Think Telstar.

This is Duncan’s home region, where he grew up.

He paused by a stone hole in the side of a wild wooded lane along St Anthony’s Creek. “A wild man lived here in the early 20th century. People would bring him food. He was proper crazy. Scampered about on all fours.”

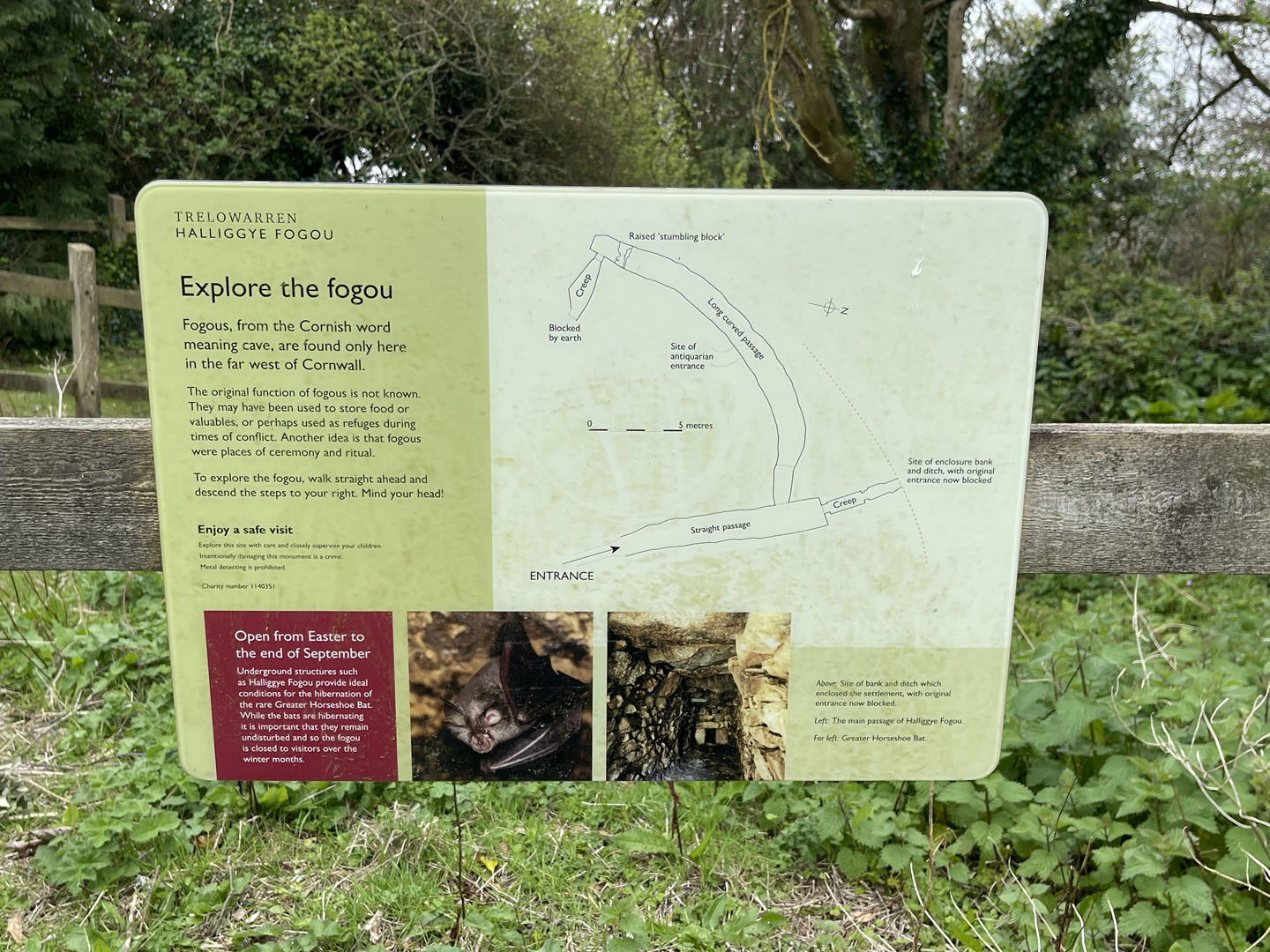

Our next goal was a remote stone age structure called a fogou (Fo Go.) I’d told him I like megalithic stuff. We parked next to a remote farm field and walked the Halliggye Path to a mysterious hill structure. It was about 50 feet high and nearly conical. Not nearly big enough to be a hill fort, its purpose is unknown. Observation? Worship? Stairway to Heaven? We couldn’t find the fogou. We were giving up when my son found it on his phone.

“We need to drive around the farm field.”

The way led down a dirt road—more of a path. A couple of spots were flooded. I cautioned not to risk it. We were far from anything remotely civilized. If we got stuck, we would be doomed. But the phone got us to it, and we climbed between rails on a fence to get in. A sign said it was open, but an iron gate disputed that. Perhaps the rare bats are still hibernating. Still, you could see down about 60 feet of a stone-lined chamber may be ten feet beneath the surface.

It goes much further than this.

I thought it was an early passage tomb like I’d seen in Ireland, but the sign said its purpose was a mystery.

From there, we headed to The Lizard. That is a peninsula and a town that extends from the far southwestern part of the Cornwall Peninsula. Its tip is the southernmost point of the island of Great Britain. No one knows why it is named The Lizard. The town is quaint. I hoped there would be a marker on the house where Tolkien holidayed. He wrote a story there called “The Lost Road.” That foreshadows The Lord of the Rings. I recalled he spent time in Cornwall from the exhibition I made a special trip to the Morgan Library to see in 2019. He also painted there, and Duncan drove us to a remote outlook, which he parsed as a location. Sickert and others certainly painted from that rock.

Duncan also found a reference that claimed the Lizard Point lighthouse may have inspired Tolkien’s Eye of Sauron.

I can see that—kinda.

We had the best pasty in Cornwall at Anne’s. I found a Lizard hoodie and a Lizard gin—my only purchases thus far.

A few more stops, and then Duncan gave a brief tour of St Ives, where we would spend the next two nights.

It is another picturesque town like Padstow, only this is on the ocean. It is incredibly beautiful.

My son booked the hotel, and we were given a room with a view. It is just above rocks upon which the waves crashed all night and day. In the distance, there is a lighthouse—as in Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse.

I awoke a couple of times in the night. The sounds of wind and waves don’t vary much. It is more of a constant humming roar. White noise. It was moonless or overcast, and there were no colors on the sea when I looked out the window. Just variations of gray and black. I wrote a little verse about it which is appended at the end.

The Beginning of the trip.

I worked hard at the warehouse on Saturday. The flight wasn’t until 10:45pm, so I got a full day in. Lord only knows what I’ll face when I return.

The flight to Heathrow was smooth. My health scare still loomed, but all the numbers seemed to have returned to normal. I test myself several times a day.

I slept fitfully on the plane, but I feel rested.

I am ready for Cornwall.

The magic land of Lyonesse.

King Arthur.

Tintagel.

Land’s End.

We are flying over Wales now. We passed over southern Ireland. The first point of contact from the west was Tralee, where I played golf with three buddies. Was it nine years ago? A seaside course. I recall a violent tide rushing into the River Lee. A few fishing boats struggled against it. They were somehow able to maintain their position against the swirling rolling waters rushing into the River Lee from Tralee Bay. I presume they were fishing.

Now the screen says we are over Rhondda. I don’t recall ever visiting there, though I’ve been to Wales many times. One of the first record albums I bought with my saved up allowance—was it 25 cents a week?—was Cher’s All I Really Want To Do. She was cool then. Not the iconic parody she was to become. I remember kissing her face that filled the album jacket. It was my first romantic, chaste kiss. LOL. 11 or 12 years old. Of course, the Byrds’ Mr. Tambourine Man was purchased soon after. It was such a new sound. “The Bells of Rhymney” struck me on both albums for some reason. The churches carry on a dialogue amongst themselves. My brother, Jimmie, told me they were Welsh church bells.

Rhondda.

I’ve been to Wales many times, but I don’t think I have ever looked for the bells cited in the song.

Perhaps one day.

Bells Of Rhymney

Oh what will you give me?

Say the sad bells of Rhymney.

Is there hope for the future?

Cry the brown bells of Merthyr.

Who made the mine owner?

Say the black bells of Rhondda.

And who robbed the miner?

Cry the grim bells of Blaina.

They will plunder will-nilly,

Cry the bells of Caerphilly.

They have fangs, they have teeth,

Shout the loud bells of Neath.

Even God is uneasy,

Say the moist bells of Swansea.

And what will you give me?

Say the sad bells of Rhymney.

Throw the vandals in court,

Say the bells of Newport.

All will be well if, if, if,

Cry the green bells of Cardiff.

Why so worried, sisters why?

Sang the silver bells of Wye.

And what will you give me?

Say the sad bells of Rhymney?

Now we are passing over London just below. I love London. To me, it is infinite.

We were met just beyond customs at Heathrow. Customs nowadays is a breeze. It is all facial recognition in Dulles and Heathrow. You enter a small grocery-store-type checkout lane. There is a plexiglass gate in front and in back of you. You put your passport into a scanner. A TV screen rises or lowers to your face height. It somehow focuses on your face and snaps a picture. If everything matches, the gate in front of you opens, and you are through. You no longer need to talk to a human to have your passport stamped—unless there is a problem.

Our guide was holding a sign with our name written on it. My son and I have nearly identical names.

He led us to his car with Tour Cornwall emblazoned on its sides. Soon, we were heading south and west from London.

It is a long way to Cornwall. A long, LONG way.

The highway passed by Runnymede—where the Magna Carta was signed.

Duncan, our guide, asked if we wanted to see anything in particular.

“Typically, we take people to Stonehenge and Salisbury Cathedral. They’re pretty much on the way.”

I’ve seen Stonehenge a few times. That’s enough, unless it is dawn on a solstice or sunset on an equinox. But I hadn’t been to Salisbury since the kids were pretty little.

“Salisbury would be cool.”

It was. It is a soaring, evocative cathedral. In the chapter house, there is one of four copies of the Magna Carta. It is in a little closet-like structure to keep the light off it.

I have a fancy facsimile of the Magna Carta framed and hanging just inside my office.

From there, we headed to Glastonbury.

Chalk another thing off the bucket list. And it was all serendipitous!

There were Biblical connections with early Christian lore. Joseph of Arimathea, who donated the tomb for Christ, came to Glastonbury. Where he struck his staff into the earth, a thorn tree grew—for nearly 2000 years. The original Holy Thorn died a while back. Its replacement was vandalized a dozen years ago. Perhaps a Pagan or Druid—who abound in Glastonbury. That died. But there are supposed to be many grafted survivors around. The legend also states it only blooms on Christmas.

The ruined abbey in Glastonbury is aglow with spirituality. Arthurian connections abound.

The town is awash with another kind of spirituality. Pagan, Druid, Wicca. Its denizens look like a Grateful Dead show. Old hippies or younger ones trying to catch a past they weren’t born for. LOTS of them. The town’s economy is driven by these folks as well. A lot of the shops are about goddesses or supplies for wannabe goddesses.

Duncan dropped at the Chalice Well. It is a strange cavern-like place. Dark. Illuminated by hundreds of candles. Strange folk—were they witches and warlocks?—were bathing in pools or seated on stone benches. Very strange…

Up the hill is Glastonbury Tor. There is a tower atop a high anomalous hill. We climbed it for the view over a vast plain.

“I think this hill may be hollow. And the plain down there used to be flooded. That could have been where the Lady of the Lake was…”

I was exhausted when we finally got to our hotel in the picturesque town of Padstow.

My son had found places to eat each night. Fancy places. This first night was a Rick Stein restaurant called Seafood. It was wonderful.

This melange includes winkles and whelks.

We got up early the next morning and headed out along the estuary. There were signs warning of quicksand—so don’t go wandering on the river bars. There were spots labeled “Sinking Sand” all over the warning sign. All the cartoons and bad movies I saw as a kid… I thought quicksand would be a regular thing in adult life.

Dog walking is a religion in Cornwall. Dog’s Welcome signs are everywhere, Shows. Cafes. Guesthouses. Everyone wants people to know that dogs are fine in here.

Walking along the estuary in Padstow most everyone was walking their dog or dogs.

“Good morning.”

“Good morning.”

“Good morning.”

…

Everyone we encountered gave us a friendly greeting.

Dogs were walked along country roads.

On cliff paths.

Everywhere there were dogs on leads.

Duncan picked us up at 9. We headed for a day of gem-like country churches and a country house (Pencarrow.) One of the lords there worked in MI5 during World War Two with Ian Fleming. Supposedly James Bond was modeled in part after him. His portrait did evoke a man with a secret life. The library was stunning. It was mostly collected by a woman, Lady Ascot.

I snapped this picture of her before I was warned nicely, “Sorry. No photos. Maybe things will get back to normal some day,” she apologized.

Then it was off to the cliffs. Duncan knows a back way to Tintagel.

We were at the end of a dirt road, and only a couple people were around.

“I think this is the best view of the island.”

We stood in awe. King Arthur. Merlin’s Cave.

We went down to the town and paid our fee. The modern route is a footbridge to the high island. It was a pretty tough hike—but not nearly the rough route before the bridge was built. On the top of Tintagel, there was magic at every turn. The views were eternal north, south and westward.

Tuesday, we were picked up by Tim Uff. He owns Tour Cornwall. He took us past Roche Rock. There was an iconic painting from around 1800 in Pencarrow House. The guide there said the hermit that lived atop it was a leper. That was why he would lower a basket for donations of food and water.

Our guides thought he was a hermit monk.

Perhaps he was a leprous hermit monk.

Tim walked through Heligan Gardens with us. Duncan joined us there.

Tim was great at identifying the plants and explaining the workings of the acres that had slept under decades of leaf mold.

Friday.

My deadline.

I’ve left out so much.

It’s been tough writing while bouncing and swaying. Two others in the car with me. I hope the writing isn’t too jerky.

We are heading from another great house. Lanhydrock. We are heading down to Foweys where du Maurier spent much of her life at Menabiliy.

There is also a hotel there that may have been the model for Toad Hall. “Poop. Poop.”

Here’s a list of some of the mythological creatures in Cornwall. I’m sure there are more, but these are the only ones I saw:

Witches. Mother’s Ivey’s Beach. She cursed the land where long ago a wealthy landowner spread fish upon the land as fertilizer rather than feed the poor. The curse lasts til this day.

Mythic creatures. The Beast of Bodmin. A phantom black cat big as a jaguar that terrifies the Bodmin Moor.

Giants. Cormoran. Who built Saint Michael’s Mount and ate cattle and children. Cormoran and another giant on Trencrom Hill were also responsible for the huge boulders in west Cornwall. They taunted and fought one another, constantly tossing boulders at each other. And then there was Bedruthan, who built the Bedruthan Steps as stepping stones to traverse the bay at Carnewas.

The Devil’s Tor. A tower atop a hill where the devil dances on the solstice, and woe to any girls dancing round the stone circle below it.

Mermaids.

Pysgies (think Pixies.)

Sea Night

In a room above the sea

Virginia Woolf’s lighthouse

blinks far in the distance

At night there is no color

Black and grays are framed

by the window beside the bed

Silvery sea foam

flies as waves blast

the invisible rocky shore below

The constant muted roar

breaches the thin glass

separating warmth and safety

from wind and wave without

I will stick to shore

The land does not move beneath my bed

Pull the bedclothes to my neck

and on the pillow rest my head

There are no comments to display.