Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.

(Try to listen to the song below while you read the first paragraphs following.)

I’ve listened to the 1971 song—”And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda”—a hundred times… or a thousand. Currently, it pops up on my Pandora folk “stations” pretty often. It is a very evocative song. But I never understood its scope until I visited Gallipoli on January 30, 2024—nearly 109 years after the battle.

I’ve always loved “Waltzing Matilda”—Australia’s most famous “bush ballad.” It is a light and happy song.

“And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda”… is a much darker sequel.

I’m writing this on a tour of Turkey. Just a week, squeezing in as much history and culture and geography as the tour company can.

The bus left the Artisan Hotel in European Istanbul early on Tuesday, January 30th. We headed south first along the western coast of the Bosporus. Then the coast of the Sea of Marmora. Then down the long, long thin Peninsula of Gallipoli along the coast of the Dardanelles.

In ancient times, that body of water was known as the Hellespont.

It is the only sea road from the Mediterranean Sea to the Black Sea—the Dardanelles—the Sea of Marmara—the Bosporus.

That path also separates Europe from Asia.

I was curious about the history of the World War 1 campaign for control of that water road.

Gallipoli.

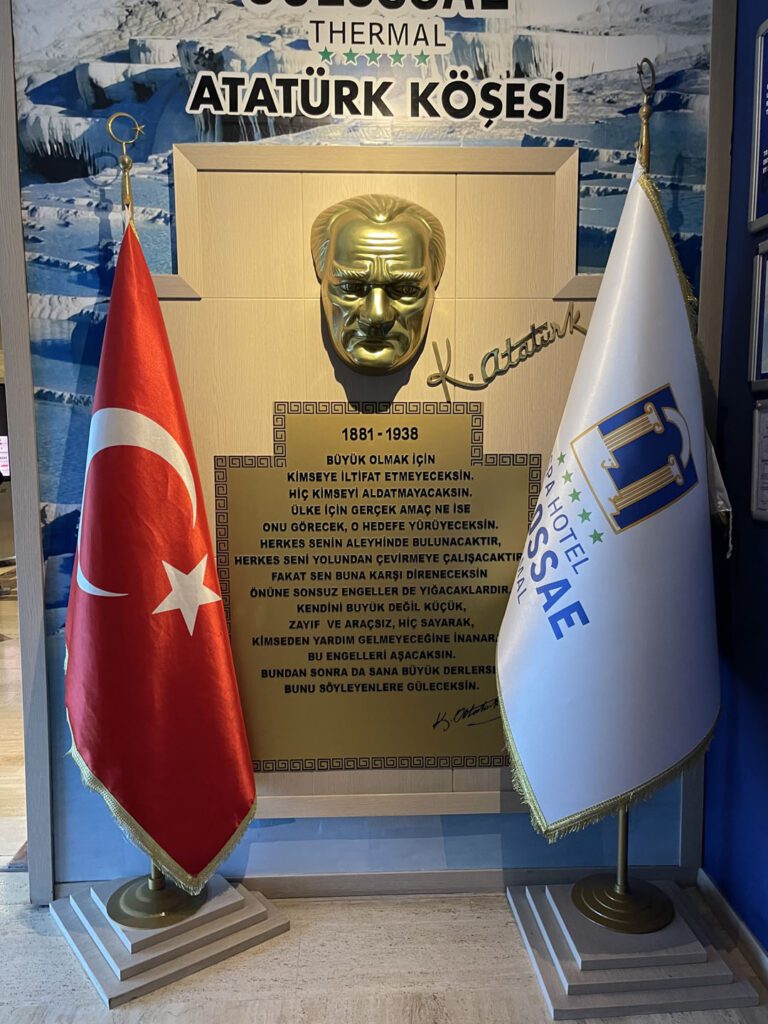

We got toward the end the end of the peninsula, and the guide’s voice narrated some of the history. Taner is Turkish. The Battle of Gallipoli is a defining event in the history of the Turkish state. A man named Kemal was a successful Turkish commander there. Later, he changed his name to Ataturk when he transformed the ancient Ottoman caliphate into a modern western secular democracy. (His images are everywhere in Turkey. Many are nearly shrines. This bronze bust was on a wall in a hotel we stayed. I sat at a nearby table having a beer while waiting to go to dinner. Several young mothers, independent of one another, came and caressed his face gently—as if in adoration. He’s been dead for nearly 90 years.)

The first stop was ANZAC Cove. I write this just after midnight February 1st, but I believe that in my mind I can stand at ANZAC Cove anytime my mind wishes until the day I die.

Gallipoli defines the futility of war. The Brits sent their colonial boys from Australia and New Zealand and India and New Foundland—the French were there too—to fight “Johnny Turk” in a sideshow to World War 1. The Ottoman Turks had joined the war on the German side. While the trench warfare was horrifically killing both sides in Western Europe between France and Germany, it was thought that a great advantage was to be had if the Entente forces (Great Britain, France and Russia) controlled the sea route to the Black Sea and Russia. Russia was an ally, after all.

Tragic miscalculations on both sides made the Gallipoli Campaign a slaughterhouse, killing or wounding 350,000 to half a million on both sides.

Boys from half a world away were cast onto anonymous shores on a nondescript peninsula jutting into the eastern Aegean.

(I write this after midnight—Thursday morning. February 1st. The Aegean Sea waves and winds battering the shore below my hotel room.)

It was cold—39 degrees—windy, wet and gray.

We stopped at the cove where the ANZAC (Australia and New Zealand) forces landed in 1915.

And the band played Waltzing Matilda

When the ship pulled away from the quay

And amid all the tears, flag waving and cheers

We sailed off for Gallipoli

Most of the lads had no idea why they were fighting here so far from home and so far from England.

And how well I remember that terrible day, how our blood stained the sand and the water

And of how in that hell that they called Suvla Bay, we were butchered like lambs at the slaughter

Johnny Turk he was waiting, he’d primed himself well, he showered us with bullets

And he rained us with shell, and in five minutes flat, he’d blown us all straight to hell

Nearly blew us right back to Australia

But the band played Waltzing Matilda, when we stopped to bury our slain

We buried ours, and the Turks buried theirs, then we started all over again

“You’ll come a waltzing Matilda with me…”

And we drove past small cemeteries with rows of small stone markers.

Tears welled, and a few spilled. The icy wind off the Aegean bit hard wherever I turned.

Boys lie dead all around beneath the cold wind swept ground.

Dead over a century now. Small low stones row after row.

So far from home.

And those that were left, well we tried to survive, in that mad world of blood, death and fire

And for ten weary weeks I kept myself alive, though around me the corpses piled higher

Then a big Turkish shell knocked me arse over head, and when I woke up in my hospital bed

And saw what it had done, well I wished I was dead: never knew there was worse things than dyin’

For I’ll go no more waltzing Matilda, all around the green bush far and free

To hang tent and pegs, a man needs both legs-no more waltzing Matilda for me

Many of the trenches remain. Boys fought boys only 8 yards apart. Close enough to see the color of each other’s eyes.

And so now every April, I sit on me porch, and I watch the parades pass before me

And I see my old comrades, how proudly they march, reviving old dreams of past glories

And the old men march slowly, old bones stiff and sore, the forgotten heroes of a forgotten war

And the young people ask, what are they marching for? …and I ask myself the same question

The war resulted in the 90% reduction of the Ottoman Empire.

There were nearly 10 million dead in the War to End All Wars.

Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

Who’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda with me?

And their ghosts may be heard as they march by the billabong

So who’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda with me?

It is said that in many wars, the slaughter would be far different if the combatants were old men—officers and politicians—rather than the young,

There are many small graveyards along the road and likely many more out of sight.

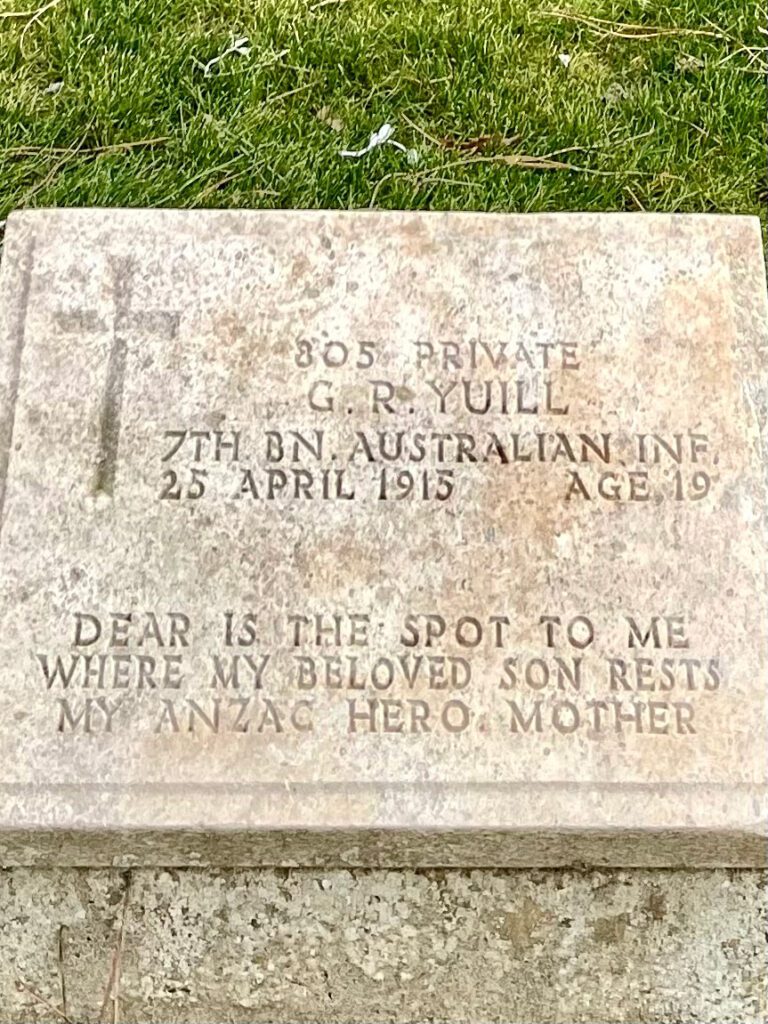

Square headstones for the Entente Alliance (France, United Kingdom, Russia, United States, Italy and Japan.)

Rounded stones for the Central Powers Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria)—almost all were Turks buried on Gallipoli.

It was all very good to have read and studied Gallipoli in books, but standing on the shore looking out on ANZAC Cove, the history and tragedy are brought to life. Walking among the graves reading the dates—19, 23, 18, 27… years old. 109 years on, I can still feel the surprise, the shock, the horror, the pain—whatever one feels when life is unexpectedly ending—of thousands of young men smacked into the reality that some kinds of death in war are not glorious but rather they are dirty, wet, bloody.

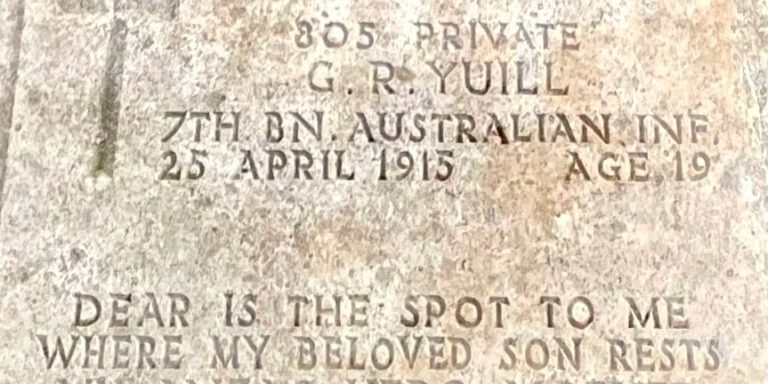

Most graves don’t bear heroic sentiments. Most just give a name, the beginning and ending date and the unit the soldier was a member of. That’s all that’s left of the youngster who came here from thousands of miles away seeking… what… glory?

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks

Wilfred Owen

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame, all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin,

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer,

Bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

To leave the peninsula, the big bus drove onto a ferry. The engine roared to life, and the boat pulled away from the quay. We were crossing the Dardanelles to the city of Canakkale.

Rather than sit on the bus during the crossing, I took the iron steps to the upper deck.

To the north was the Sea of Marmara. To the south, the Aegean.

The ferry had launched so as not to be in the way of any freighter or tanker passing north or south.

The guide said three thousand ships pass this way each day.

Though it was bitter cold and spitting icy rain and the wind was whipping so hard, I stayed outside on the upper deck. How often does one get to cross a body of water that has seen mariners pass through, likely since mankind first took to the sea in boats? I pulled my knit cap down tight—for warmth, but mostly to keep it from blowing off.

At some point, we left Europe for Asia.

(Our guide told us Turkey has an identity crisis. It straddles both Europe and Asia. But the West doesn’t consider it “Western.” The Middle East doesn’t consider it Middle Eastern. I suppose one could consider it both.)

When we docked, Taner, the guide, had the driver go through town. He wanted us to see the giant wooden horse that had been given to the city by the producers of the movie Troy.

For that was our next stop. The ruins of ancient Troy.

It was late afternoon by the time we pulled into the very rustic parking lot of the archaeological site. We disembarked onto the wet gravel.

The wind picked up even more, and the temperature dropped. Everyone bundled up and clustered around our guide, Taner. Each of us was issued a “Whisper” device. It is a small box about half the size of a cigarette pack. There’s a light strap to go around your neck and a couple feet of wire with an earpiece at its end. The device allows the guide to broadcast to our ears. He can speak in a low voice, and as long as you are within thirty feet or so, you can hear his every word.

And every breath.

Today, we heard his voice competing with nature. The wind whipping round was amplified through his microphone.

He led us onto the wooden boardwalk that weaves through the 11 or so layers of the ruins of “Troy” in the complex.

The wind picked up markedly. Taner’s words were crackling and hissing in the wind. It was so cold and wet with spitting rain. The late afternoon sun behind the clouds was dimming.

The wooden boardwalk was uneven and periodically presented steps down or up. I had to remind myself, ‘Don’t trip and fall here so far away from everything.’

There are eleven layers of cities on the site. Much of it looks like rubble to my eye. But some walls are identifiable.

Is this the ramp that the wooden horse was pushed up and into the walled city?

The boardwalk crosses crumbling ramparts and stone or mud-brick walls. Signs explained what you are seeing. Taner added data that made the drab stones even more intriguing.

I look across the plain beyond the wall to the west.

‘That’s the Aegean in the distance,’ I thought. ‘Is that the shore where Achilles, Menelaus, Odysseus and the other Greeks camped for ten years before they captured the city?’

A wide flat plain still lies between the citadel and shore.

Troy!

I have been to Troy.

As a kid, as a young man, as an older man, I never thought of Homer alive—seeable—touchable.

It was dusk by the time we got back to the parking lot.

(Yep, I bought a Trojan hoodie.)

Though they weren’t the grandest ancient ruins, it was “Troy.”

Treasures and been found there.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Priam’s_Treasure

Treasures lost.

Forever?

Maybe…

Maybe it is just buried once more—perhaps in a Soviet-era Indiana Jones-like warehouse.

Everyone was cold, damp and windblown when we boarded the bus. Fortunately, we were only a short drive from where we were going to stay.

The hotel was on the water—the Dardanelles—a beautiful and modern place.

It was still very cold and windy. We had a late dinner. I hit the COVID wall of exhaustion. I went up and crashed onto the bed.

I had troubled dreams. My mind was churning. Outside, the rain and wind escalated very late to a roaring storm. The window in my room on the sixth floor began screaming with wind and rain. It woke me. I went to my shaving kit and got earplugs out so I could return to sleep.

All of the above was Tuesday, January 30.

This adventure actually began last Friday.

In Maryland. At home.

What with the COVID remnants, the suddenly bad back, the futile attempt to get caught up at work, I didn’t prepare for the trip beyond noting the time and date of my flight.

‘Turkey is warm, isn’t it? Dry too. Palm trees. Oranges. Sultana grapes and raisins,’ I thought.

I quickly looked at the weather for Istanbul on my phone. 50s. Not terrible.

I went through my mental overseas trip list.

Passport. Electricity adapter. Charging cables for the laptop and iPhone. Medicine.

I found some pants and socks. Hoodies warm enough? Raincoat? Why not? Something to read? Philip K Dick (K stands for Kindred. Died 1982. Age 53. Wrote all his pre-1970 works while on speed.) Time Out of Joint—might as well. I just started it.

Gather up the dogs and their stuff.

Turn off the well pump and the water heater. Open some taps to drain the pipes. (It could be a disaster if the power went off up here and the pipes froze while I was away.)

Set the cameras and the alarms.

Go to work.

Get as much done as possible.

Panic about leaving too late.

The airline texts, “Flight delayed until…”

Go back to the warehouse floor and work a couple of hours more.

I left the Frederick book warehouse about 3 p.m. on Friday. I wanted to allow extra time in case the traffic was bad to Dulles on a Friday afternoon.

The flight delay—flight times are now a very fungible data point.

I got to Dulles about 4:15.

At the Air France check-in, I asked a question I’ve never asked before.

“Can I pay for an upgrade?”

My snowplowing back injury seemed a lot better. I didn’t want to test its endurance with long flights to Paris and from Paris to Istanbul crunched up in economy.

When it hurts—it REALLY hurts.

“Yes,” I was told.

The price for business class was much less than I thought it would be. Still, it was a ton of money for a 6.5-7 hour flight.

“Ok. I’ll take it.”

I’m taking a weeklong tour of Turkey. A whirlwind tour. There will be long drives almost every day. Crazy long. I can deal with that. Or can I? The bus seats are cramped if two people share the bench. The seat in front of you nearly brushes your knees when it ISN’T being reclined.

How would my back react to hours seated, bouncing on roads, with little or no room for my legs and nowhere to stand and walk and stretch?

December was eaten up by the trip to Portugal and the onset of a nasty bout with COVID the week before Christmas. January was a slow recovery from COVID with a bad chronic cough lingering and tiredness/weakness hitting me whenever it felt like it. Three snowstorms in ten days in January trapping me on the mountain for at least a day each added to the drama. (And the absenteeism.) Injuring my back while plowing and salting was the coup de gras.

Could I handle the trip physically?

TROY!!!

I’ll take my chances. What’s the worst that could happen? I could die in some remote place in Asian Turkey. I could become immobile in some remote stop. I could be in pain and a burden to the traveling companions.

I seriously considered canceling.

That would cost money. It would be the fourth trip canceled in the past 6 months.

And I really wanted to go.

All my adult life, I’ve been able to “buck up” and power through obstacles—physically and mentally. Sometimes mind over matter is real, I believe.

I decided to go.

My back was almost better. My cough was almost gone. Maryland had heated up—75 degrees on Friday… unbelievable.

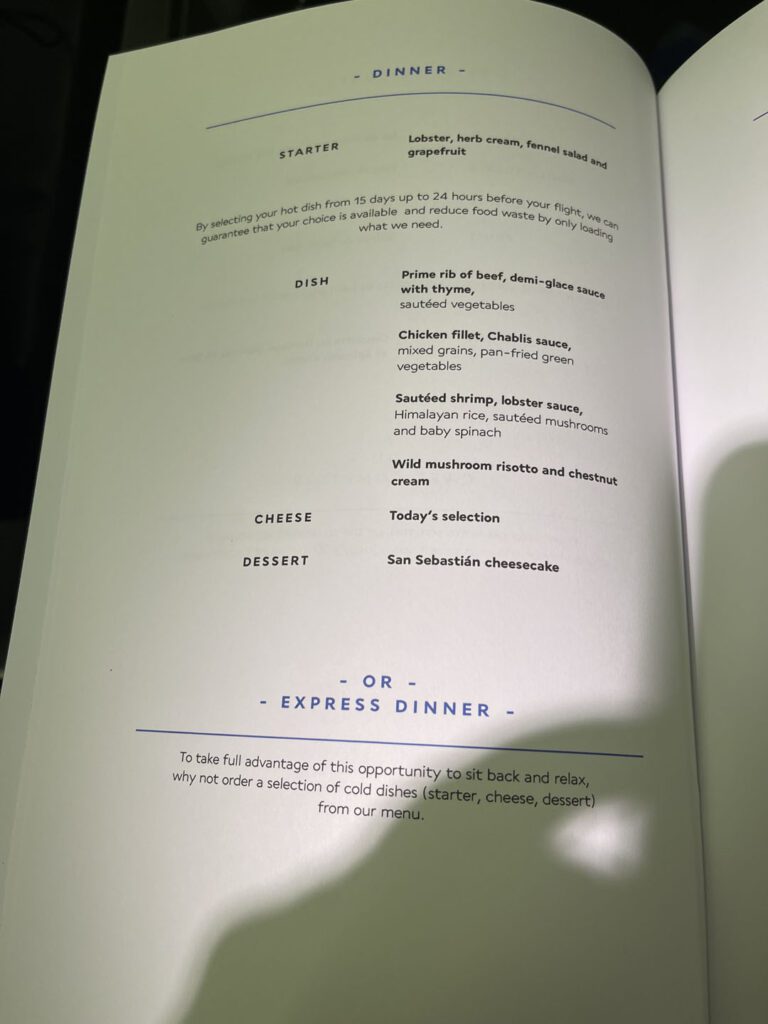

I flew in luxury from Dulles to de Gaulle. My seat could recline into a kind of narrow bed.

Champagne (real) flowed from the moment I sat down. Fancy food was offered.

I partook of a little and then shut down—reclining completely and pulling the blanket over me. I felt good at the 8 a.m. landing in Paris.

It was the usual “comedy” getting to the right gate in that vast airport. I won’t bore you with the minutiae—except for the last half hour when our gate changed three times.

Really.

At least they were close to each other.

Flying from Paris to Istanbul.

Charles de Gaulle was the usual disaster. After delays (now to be expected rather than unusual), the flight from Dulles finally took off nearly three hours late.

Delays cause the “margin of error” to become thinner. The 4 hours planned in Paris to navigate de Gaulle were whittled down to 2.

I’ve nearly missed connections in Paris a number of times recently. The French have a quirk of putting transfer passengers through screenings even though you were screened to get there and you’re not staying in France or even the EU. You’re just going to hop on a plane and skedaddle elsewhere as quickly as possible.

But, no, France wants to check you out even though you’ve been controlled since the second you got into the building. (And since you passed through the security gauntlet and qualified to be boarded back in the US.

To make a long story short—I went to two terminals, four gates and had me and my knapsack screened twice.

Long lines at the inside of the airport scanning stations—as usual. After being sent to Terminal F, I was told after standing in line to be screened that my flight was at Terminal… some other letter. The two guys who gave contradicting advice could have been twins—and they were dressed identically.

Fortunately, I didn’t have to run. I got to the correct gate with about 45 minutes til boarding was to begin.

The folly ended with three gate changes in the final 15 minutes. Fortunately, those gates were close to one another. It was funny to watch my fellow passengers move as a herd a few hundred steps when the sign changed.

So many people are so anxious to board they line up at their numbered queue 45 minutes in advance. There they stand and wait to be the first in their group. First or last, they’re going to end up in their reserved seat.

Well, the first ended up last. Then the new firsts ended up…

Next stop Asia. Or close to it. I don’t know if the airport is on the Asian side or the European side of the Bosporus.

We are coming up on the Alps. Snow-covered jagged peaks as far as I can see from 35,000 feet up. The sun, far to the south, is pouring in the porthole like window next to me. The warmth feels good and makes me sleepier.

I’m tired. I’ve nodded off a few times in the first hour of the flight from Paris to Istanbul. It will be about 5 p.m. there. I think my body will feel like it is 9 a.m.

Should I caffeinate or try to write?

So often I long for time to write. But right now, blessed with downtime and a captive in the window seat with two sleeping humans to my left, I’m just too drained to do anything.

There’s no TV on this plane.

Finally, we are descending to Istanbul.

Descending through an endless blanket of white clouds, which turned to slate gray the lower we got.

Then I could see the sea below. It was even a darker gray and choppy, as if in random turmoil, as if it was at war with itself.

What body of water was it? I don’t know. No TV means no way to track your flight.

It took quite a while to find my transfer driver. He or she is supposed to be holding a sign somewhere outside the arrivals.

Now I’m in bed at the Artisan Hotel.

There was no question of going out on Saturday night.

It was dark, windy and raining hard when my transfer dropped me off.

I opted for a couple of Turkish beers and a traditional Turkish/Muslim dish called Byzantine-style Tharid. It is said the Prophet liked Tharid.

It was good. I was seated the hotel bar, and two American women joined. They had been on the same shuttle with me. We chatted until I was toast and went to bed.

I awoke early on Sunday, but my body thought better of it and curled itself up to sleep some more.

It was nearly 11 a.m. before I really woke up, showered, had breakfast and ventured out.

I never sleep that late.

Istanbul.

It is Sunday, late morning here. 3 a.m. at home.

I slept long and hard. My phone seems unsure of the time here. When I awoke, I swear it said 10:56.

“I missed breakfast!”

But I took a chance and went up, anyway. Maybe I could still get coffee. When I got up to the rooftop restaurant, the phone said it was just after 10. The place overlooks the Bosporus.

I’m looking at Asia from Europe with the Bosporus in between.

Istanbul—the city that is on two continents.

Istanbul.

5229 miles from Washington D.C.

Istanbul (Turkish: İstanbul) is the largest city in Turkey, serving as the country’s economic, cultural and historic hub. The city straddles the Bosporus Strait, lying in both Europe and Asia, and has a population of over 15 million residents, comprising 19% of the population of Turkey. Istanbul is the most populous European city and the world’s 15th largest city.

Wikipedia

I looked on the map for something to do on Sunday afternoon. Something close. I was still tired. I didn’t want to try to figure a way over to Asian Istanbul.

The Dolmabahce Palace was only a ten-minute walk—whatever it is.

The narrow flat area along the Bosporus shore had a lot of people. Is Sunday a holiday here?

I got in the long line. Way up ahead, I saw the prices.

150 Turkish Lira (about $4.50) for Turkish citizens.

1050 Turkish Lira ($34.50) for “Foreigners.”

WHAT??

After going through the Dolmabahce Palace (it was fine but no big deal), I headed for the adjacent Art Museum.

I thought the sign said “Modern” somewhere.

It was mostly 19th and early 20th century canvases.

Sultans, sultans everywhere.

The definition of “Modern” in this museum was mostly portraits of sultans and caliphs over the centuries. I don’t recall any 20th century canvases and certainly nothing beyond different kinds of representational art.

There were also a couple of small galleries devoted to women—many from harems.

Several galleries were devoted to “Victories and War.” Landscapes of battles mostly, but also some naval battles as well.

It was interesting. I like paintings, and all these were new to me… different.

It was clear that a priority would be finding cold weather things. Gloves, knit cap, scarf…

My phone said any retail stores would be up a steep hill. (Istanbul is said to be built on 7 hills—just like some other great cities.) The walk back to my hotel would be about a hundred stone steps up from the Bosporus. The same steps I had descended to get here.

Then I recalled walking past a soccer stadium to get to the palace—Beşiktaş (ba-sheik-shtas.) Turkey is soccer crazy, and this team is one of the big ones. I had sent images of it to my sons. One plays. The other referees still.

Would their team’s gift shop be open? It was only a dozen steps up after crossing the packed waterside street.

Success! I got Beşiktaş logoed gloves, scarf, knit cap and… a hoodie.

(It is Friday. February 2nd. 7 a.m. Exactly. A call to prayer is being sung somewhere outside the hotel. Turkey has a lot of mosques. Instead of steeples, towns and landscapes and small cities have minarets reaching for heaven. It is still dark. The muezzin’s song is broadcast for about 8 minutes before the quiet of morning returns.)

I left the stadium with my new cold-weather gear and went up the steps to the street that led to the hotel. I had to pause a couple of times. My stamina has not come back yet. Nursing myself back from COVID and hurting my back has caused a lot of down time.

Then it was Monday evening. My body is still in motion. We walked a lot in Istanbul. Almost 20,000 steps. In the rain and wind. Cold, cold rain.

Trial by fire… uh, no—ice.

Back in the hotel bar. 39 degrees and rain.

Most of the group went to a belly and folk dance show and dinner as an “optional” excursion.

I saw belly dancing in Morocco. Or was it Athens—in early 2023.

So I’m staying in. I’m glad because I’m exhausted. I’m still hitting a wall in the late afternoon. Either it is continuing COVID fatigue, or perhaps I haven’t regained my stamina.

I looked back on the first day of the “tour.”

You can bundle up only so much. And the umbrella doesn’t shield you against horizontal rain.

And my sneakers are not rainproof. Nor puddleproof.

When we got back to the hotel about 6, I immediately went to my room and took a long very hot shower. I let the water batter my core temperature back to “normal.”

Now I’m having an Efes beer and waiting for a burger. Well done. Comfort food.

I’ve had enough “adventuresome” eating since I arrived on Saturday morning. I just want something I can count on.

It is evening, and I’m trying to make sure the cold and stress and exhaustion doesn’t put me into relapse for the COVID cough or the excruciating backache.

Getting ill in a foreign land would be a nightmare.

I hadn’t expected the weather here to be so bitter. Of course I didn’t look into it properly.

That morning, the bus took us as far as it could go. It is not permitted in the Old City.

The marathon tour began in Hippodrome of Constantinople. The track that once existed here wasn’t used for runners though. Our guide said it was for chariot races. There are three pillars in the infield.

A stone Egyptian artifact—the Obelisk of Theodosius “imported” here in the 4th century A.D. by the eponymous Roman emperor.

A bronze twisty column called the Serpent Column. This was “liberated” from Delphi by Constantine.

Another stone obelisk still stands as well. It is called the Walled Obelisk.

All day, we marched behind our guide like ducks in the rain.

The enormous Blue Mosque was next. You must remove your shoes to enter. That was problematic with all the rainwater. I didn’t want to squish around the vast carpet covering the floor of the mosque. With a tiny touch of acrobatics, I managed to cross the threshold and avoid a “hot foot.” I put my damp sneakers into a plastic bag supplied by our guide. It was beautiful—soaring heights. The “blue” is all the tiles on the walls. In keeping with the faith, there were no representational images of humans or animals. Lots of calligraphy and stylized flora as well as geometric shapes.

From there, we headed to the Hagia Sophia. Sophia is not a saint’s name. It means wisdom. It was a 6th century church that was converted into a mosque.

The remaining huge mosaics on the high dome are sadly covered with drapes so as not offend the mosque goers.

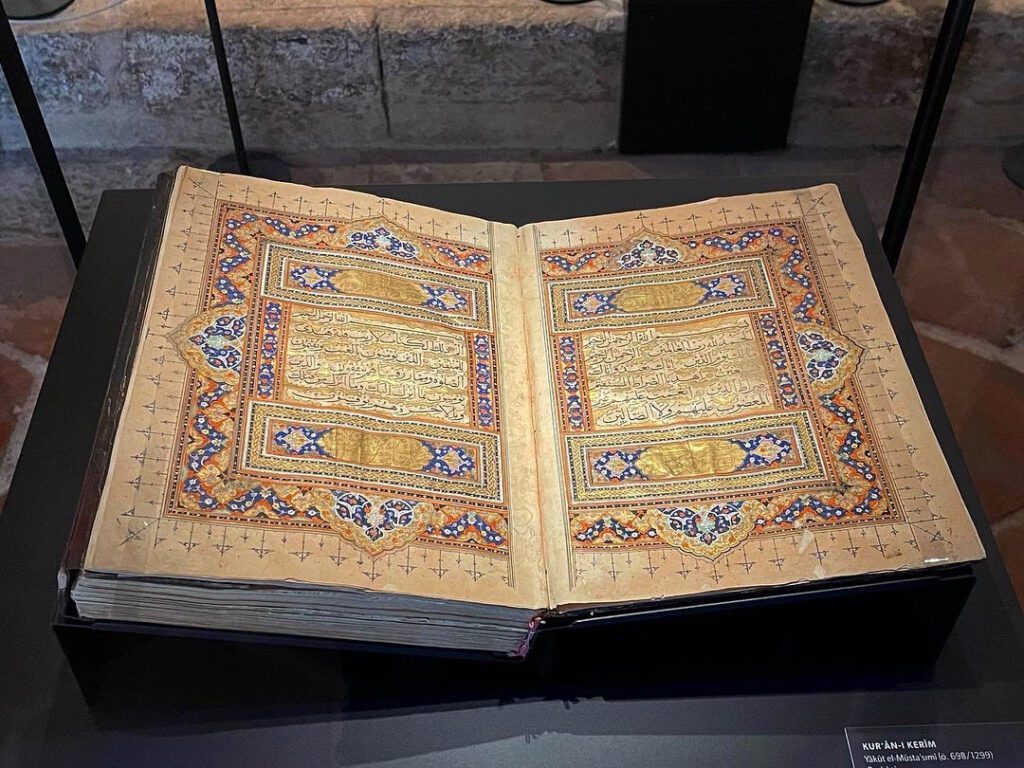

Then onto the sprawling palace museum Topkapi. It was the home and seat of government of the Ottoman Empire sultans from the 5th century to the 19th. Its buildings surround large courtyards. These buildings once housed the royal families and all the people who would support them. The kitchen, the armory, the library, the mint, harem, concubines, audience, privy chamber, etc.

Each of these has been converted into a different sort of gallery or exhibit. Of course I was drawn to the Manuscript and Calligraphy gallery.

The day was wearing on to two o’clock or so. The guide decided we should stop for lunch. I usually don’t bother with lunch, but Taner has a way of finding irresistible places. (I’m sure the owners are friends of his.) A signature dish was “Clay Pot Beef.” It comes tableside presented in a bowl of flames.

The waiter makes a show of “breaking” the pot with a small knife/sword—hitting it rhythmically like a percussion instrument. The top part eventually “breaks” off at a seam, and the waiter pours the stew-like mixture onto your plate.

The last stop was the sprawling Grand Bazaar. We were let loose for “free time” at “Gate 1” and told to meet back there in an hour and a half. I figured it was just another maze of shops, but this place was surreal. A bizarre bazaar.

It is one of the largest and oldest covered markets in the world, with 61 covered streets and over 4,000 shops on a total area of 30,700 m2, attracting between 250,000 and 400,000 visitors daily. In 2014, it was listed No.1 among the world’s most-visited tourist attractions with 91,250,000 annual visitors. The Grand Bazaar at Istanbul is often regarded as one of the first shopping malls of the world.

I started wandering and figured it would be easy to find my way back.

Nope.

I think my head was hitting the late afternoon COVID wall—when my cognitive skills begin to get short-circuited. Once I turned off the main drag, I was doomed.

The “streets” meander in a medieval grid (meaning no grid at all.) Shops repeat themselves time after time after time. None really stand out, so there are no landmarks to look for.

I probably passed 25 spice shops that all looked similar to this.

I found an exterior perimeter—”Gate 16.” Was I close to Gate 1 or very far away?

‘The iPhone can direct me out,’ I thought.

Nope. No reception.

This could get dreary. I’ll be the lost guy that keeps everyone waiting.

I was too tired and frazzled to think clearly—methodically.

“Didn’t I just pass this restaurant?”

Finally, fortune smiled on me, and I saw a clutch of three fellow travelers. I just hoped they weren’t as lost as I.

“Do you know the way out?” I asked, casting all manly pride aside.

They did.

That ended Monday for all intents and purposes.

Tuesday was the above.

Wednesday

We are heading south to Pergamon. We are in some mountains and in some “new” tunnels under some of those mountains. Soon, we will hit the coast of the Aegean and perhaps be able to see Lesbos. Much of the scenery is snow covered.

Out of the last tunnel, we exit into groves of some of Turkey’s 185 million olive trees.

The bus makes a long descent toward the coast.

And there is Sappho’s island in the distance floating on the Aegean.

Finally, some blue skies.

Finally, there is no wind whipping the trees and flags. The Turkish flag—red with a white crescent moon one white star. The horns appear to be grabbing or about to engulf the white.

Even the Aegean is quite calm.

Though I slept a long time, the long bus journey makes me sleepy. Maybe because part of me still feels like it is the 3 a.m. hour it is in Maryland and not the 11 a.m. it is here.

We are passing through tens of thousands of olive trees.

It was a long drive, but we finally got to Bergama—the modern city of Pergamon. The guide knew a good family restaurant (well, of course!) The bus pulled up, and we poured out for lunch.

The proprietor displayed the various dishes on offer with pride.

I was going to skip lunch again but surrendered to the skewered lamb and beef kabob.

The owner presented us with his pride and joy Pistachio Baklava for desert and then entertained us with a few a cappella songs.

If I should fall in a foreign land…

Next, we went to the ruins of the Asclepieion.

The sky was clear today. Azure blue.

But the wind was even more brutal. Gusts would push me off my stride, and I would lean into the wind to regain my course. The ruins were extremely uneven. Precarious drops were everywhere.

This place was kind of ancient high-end spa in ancient times. Color therapy. Music therapy. Mineral spring-water therapy. Mud. Cupping. Hunger. Satiety…

All in the name of Asclepius—the god of health. His daughters—Hygieia, Iaso, Aceso, Aegle and Panacea were also health care workers.

There were underground rooms and passages built of stone.

Columns ruined and intact. An amphitheater curves into the slope of a hill.

We went down stone steps into a maze of rooms and arches and steps and doorways.

A woman just behind my right shoulder made a soft scream. A man had fallen next to me onto a large stone paver. He went down hard onto his knees and collapsed, prone, onto all fours. Several of us rushed to his side to assist him.

Should we help him up? Or is it better he stays down?

We were essentially in a large hole in the ground in the middle of nowhere. The rough path back to the bus parking was about a half mile.

Several of us got under his armpits and slowly raised him up. He stood unsteadily, saying, “I’m ok. I’m alright.” His wife at his side, they turned and headed up the steps to ground level.

There was a collective sigh of relief—inaudible as it was—and our group regrouped.

The guide continued his lecture. And then we were released to explore on our own.

“We will meet back on the bus at 2:30.”

I walked and climbed over the ruins. The winds were buffeting the stone hollows and walls.

Near any ledges or drops, I reset my feet to lean into the wind so I wouldn’t be blown over an edge.

The man who’d fallen wasn’t ok. We came upon him seated upon a stone.

A few younger men in the group started walking him out. It was a long rocky way.

Then they got under his legs as he sat and carried him a ways.

The guide had called a friend, and young Turkish men appeared. Different options were discussed, and then a man appeared on a low motorcycle. The victim was lifted onto the seat of the motorcycle. A young man on each side steadied the injured man. The bike crawled out of Asclepieion and into the parking lot where the bus was parked. He was seated there, his wife in a small panic, until it was clear he could not get back on the bus.

Eventually, an ambulance appeared.

And that’s where we waited—outside the hospital—until the guide returned and told us the man would remain there for X-rays and perhaps tomography.

Then we headed to our hotel in a very somber mood.

The man who’d fallen ended up with a broken bone around his knee. He chose to have the surgery in the modern-looking hospital in Bergama. We’ve heard it went well. He will fly from Bergama to Istanbul. There we may see him we are told. And, maybe, he will take his original flight back to the states on Sunday.

Sounds pretty optimistic…

Sounds like it would be a miracle.

Prayers are sent his way.

January 31

I awoke in blackness from a troubled dream

There is a storm raging outside

‘Where am I?’ I wondered.

Disoriented I tried to gather my wits.

‘Where am I?’ I worried.

Troy? The First World War?

No light seeped in from the battered window

I rose and my feet searched ahead

Tentative steps inched me forward

‘Just don’t fall.’

Cold brutal death outside

‘Help me find a way,’ I prayed.

Morning’s light is still far off

I can only wait, wonder and worry

and seek shelter from the storm

There are no comments to display.