Christmas Ghosts

(This Round and Round story about the weird bookshop takes place in the present—sort of…)

It was Christmas Eve.

Gray, cold, windy.

The last customer had just left. The bookseller had humored her.

‘Probably lonely,’ he thought. ‘No one to go home to. Like me. She wants the company of books on Christmas Eve. I don’t blame her.’

While he was waiting for her to finish, he puttered around the shop doing chores that didn’t really need to be done.

Mathilda the cat and Setanta the dog both followed his movements with the bit of expectation and, at the same time, disinterest that bored pets can evoke. Their eyes half closed, but their brows ready to rise in an instant. Mathilda was perched up on the counter. Setanta was curled on the floor five feet below her.

Finally, the woman came to the front. The bookseller hurried up and moved behind the counter to serve her. In her hands, she clutched a handful of old Josephine Tey paperbacks.

‘Her gift to herself,’ the bookseller thought.

She was mature, but not matronly. She wore a fitted woolen coat of a cut long, long out of style. Her silver hair was done up in the fashion worn three quarters of a century before.

He spread the half dozen paperbacks across the counter before him. He began writing the titles and prices on the lined paper receipt in the pad. He still did this for in-house purchases. The internet book sales were all automated and spit out of the printer each morning when he pressed the button. For customers who still came to the bookstore, he felt this was more personal.

‘Ah, Tey solves the mystery of Richard III in this one,’ he thought.

“Have you read Tey before?” he asked absently.

“Long ago. So long ago, it seems it was a different era,” she replied. Her voice was very precise. She sounded like Myrna Loy or some other actress from the 1930s.

“Eighteen twenty-nine,” he quoted the tally after mentally calculating the sales tax and adding it on.

“Oh my. Their cover prices are all between a half a dollar and two.”

“Well, new books cost ten times that nowadays. There are electric bills to pay. Mathilda and Setanta have great appetites.”

“I was not complaining. Just stating the facts.” She twisted a metal turn on her glossy black leather purse and reached in. She withdrew a small magenta petit point change bag. Opening it, she withdrew a ten, five, two ones, four quarters, two dimes, a nickel and four pennies. She laid each, one by one, on the counter between herself and the bookseller.

“Why, these quarters and dimes are silver. And your pennies are wheat cents. These bills are Silver Certificates. Do you collect old money?”

“Old money? Is there something wrong with it? I do not have occasion to spend money very often.”

The bookseller looked up. Her eyes engaged his. They were brilliant turquoise.

He was taken aback for a long moment before he broke from her gaze and looked down at the counter self-consciously.

“Not at all. But silver coins are worth many times their face value nowadays. Maybe twenty times. Four quarters and two dimes… these alone are worth over twenty dollars. You should save these. Do you have a credit card?”

“Save them for what? A credit card? No. I do not have occasion to spend money often.”

“Well, let’s see. The old paper money is just face value I think. All the bills are well used. Seventeen in bills plus one twenty-five plus four cents… Wait! One of these pennies is from 1909. The “S” below the date means it was minted in San Francisco. And on the back… well, I’ll be—”V D B” along the bottom edge. I collected Lincoln cents when I was a kid. This is a rare penny.”

He looked up and met her eyes. Now they were emerald green.

“Here,” he said. “We’ll just settle for seventeen dollars—paper. You keep the coins. They’ll just keep going up in value.”

“Well, I do not know why you are making this transaction so difficult. It is Christmas Eve. I just wanted something to read this evening until St. Nicholas comes.”

The bookseller chuckled. “I’d feel guilty if I took advantage…” He met her gaze. Her eyes were golden amber. “Ummm… I’ll just slip these in a bag.”

He tore off the top copy of the receipt and marked it “PAID.” The bottom copy he tore off and slipped into the cash box with four bills.

He noticed Mathilda had risen and was standing as if overseeing the transaction. Setanta had risen onto his hind legs and was resting his fore paws on the counter just inches from the woman. He had been staring raptly at the money and the books between the two people.

The woman picked up the coins one at a time and started to drop them into her small change purse. She stopped and then she put the coins back on the counter and squeezed the purse shut. The gold clasp made the soft “click” that only gold can make.

“It is Christmas Eve. I know booksellers seldom make money. Keep the change, and Merry Christmas.” She paused and made a soft inhalation. “I see you have a help wanted sign in your window. I have not worked for ages. But perhaps I should get back into the world again. Your sign looks quite worn and faded. How long have you been hiring?”

“Forever. There’s never enough help. And when someone good comes along, they seem to leave quickly—often under unusual circumstances. I’ll give you an application. You can fill it out at your leisure and bring it back. I need some information for the accountant—the government, you know. They want their taxes and records…”

“No, I don’t know. No one knows I exist.”

“Off the grid?” He chuckled.

She produced an old fountain pen from her clutch. She pulled off its cap and filled in the top line of the application. In a flowing calligraphic hand, she wrote, “Cassiania Calleopina.”

She turned the paper around and slid it toward the bookseller.

“I will return after the first of the year and discuss terms with you.”

She turned to leave. Stopped and looked back over her shoulder. Her eyes were arctic blue.

“Merry Christmas, Bookseller.”

“I hope St. Nicholas is kind to you this evening.”

“He usually spends a couple hours, and we discuss things of great import. Faith, hope and charity. I will have some warm caraway seed cookies for him. And we will sip some Napoleon Brandy. I will sip. He will pour himself a large measure into his snifter and drink til his cheeks glow red.”

“Does he wear a red and white suit?” the bookseller chuckled.

“Heavens, no! Those advertisers at Coca Cola dreamed up that outfit long ago. I do miss Life Magazine.”

“We have plenty here.”

“You have no idea how difficult it is to find 18th century brandy. For it to be Napoleon’s, you need to check for the bee embossed on the bottle. And Nick should not imbibe too much. He has many stops.”

“I believe most people leave him milk and cookies. And usually he doesn’t stay long. He just slips down the chim…”

“You could not chat with him unless you could speak Old Eastern Slavic. I suppose his hearty ‘Ho! Ho! Ho!’ is his way of communicating with the moderns.”

There was a pause between them. She squeezed the top of her purse with the thumb and fingers of both hands and twisted the catch. It made a soft “click.”

“Merry Christmas to you,” he said.

“Merry Christmas,” she replied softly. “I should go and start the cookies. He would be very disappointed if I did not provide them. It is a tradition that goes back many years.”

A book fell to the floor from the bookcase behind the bookseller. He turned and bent and picked it up noting it was a duodecimo Latin Text in an 18th century binding.

‘What a beautiful calf binding with two red spine labels,’ he thought. ‘I don’t recall seeing it before.’

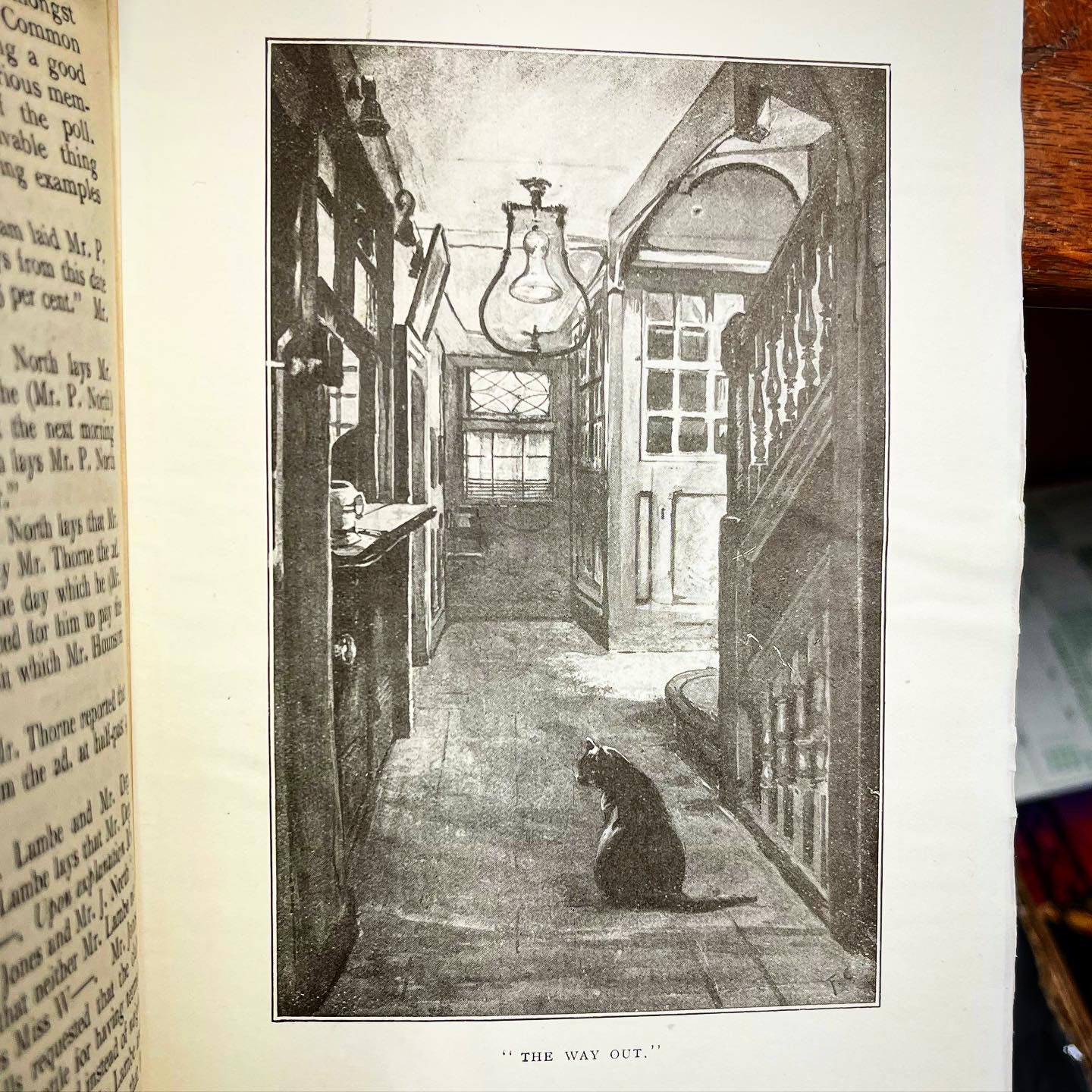

When he turned around, she was gone. The bell on the door hadn’t made a sound. He hurried to the door. Mathilda thumped to floor after him. Setanta’s claws scrabbled on the wooden floor behind them as well. He got to the door and pushed it open. The bell suspended above tinkled gingerly. He looked out. She couldn’t have crossed the porch already.

Nothing. No one. No car. No shadow. No silhouette out in the parking lot.

The fifty-three boxes of children’s books lined the porch railing. He had been putting out boxes of kids every Christmas Eve for decades now. Long ago, he had accidentally left 3 boxes of beautiful nearly new kids books outside after he had bought them from an odd little man. When he came back Christmas day, they were all gone.

Since then he had left as many boxes of nice kids books as he could outside on Christmas Eve. They were always gone by morning.

He looked up at the streetlight atop the tall pole in the center of the parking lot. At that instant, a large owl took flight from its apex.

Snowflakes were falling though the light cast by the bright bulb in the frosted glass globe suspended by a long wrought iron arm.

He stepped back inside pulling the door closed.

“Looks like we might have a white Christmas you two,” he said to the cat and dog seated and looking up at him expectantly.

He went back behind the counter and bent to reach under it.

“I have a present for each of you.”

Mathilda was up on the counter in a flash. Setanta was on his hind legs with his forepaws on the counter’s edge. He was a good five inches taller than the bookseller’s five foot eight inches.

He gently tossed a gray felt mouse to Mathilda. It was nearly the size of his fist.

“Mrs. Panthippe made this for you, Mathilda. She grew the catnip herself. She’s the one that collects Arts and Crafts press books, you know.”

Mathilda tossed it up in the air and batted it from one paw to another in her own private badminton match.

He set a 23 inch long braided rawhide strip before Setanta. It was as thick as his wrist.

“Mr. Melisanthe made this for you on his farm, Setanta. He’s the one that collects old editions of Christian mystic poetry. You fetched that late 17th century edition of St. John of the Cross for him last week. He says the rawhide is flavored like smoked turkey.”

Setanta knocked the toy to the floor and fell on it wedging it upright between his two front paws. He began gnawing on the end of it happily.

“Merry Christmas you two. And for me…” He turned and walked into his office. He returned with a bottle and a very old Waterford crystal tumbler.

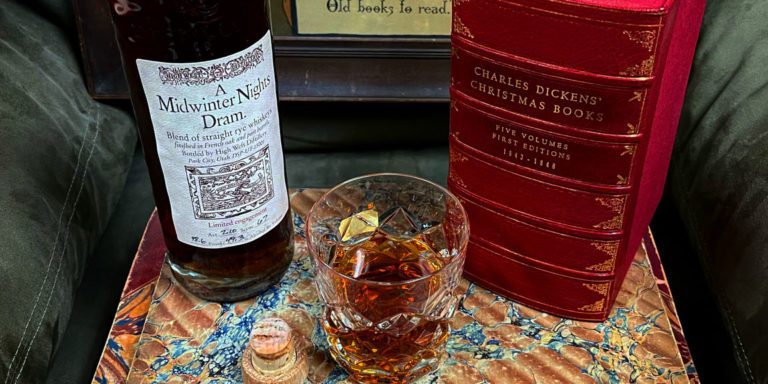

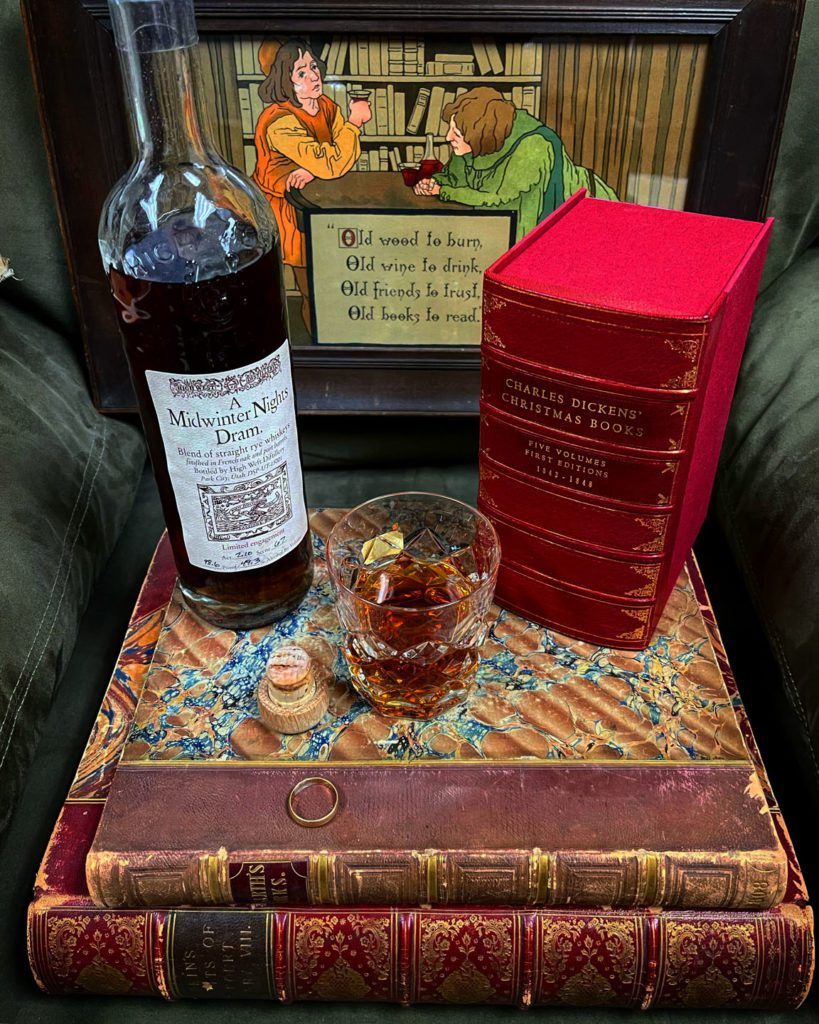

“A Midwinter’s Night Dram,” read the aged paper label in a kind of renaissance typography.

He poured two fingers of the amber liquid into the glass and set down the bottle and tapped the cork back into it s top.

“I can’t find this anymore since Ye Olde Spirits Shoppe closed. Jonathan died, you know. Loneliness after Carlotta passed away, I believe. All the other stores are either sold out or are asking $400 for a bottle.”

He took a little sip.

“Ahhhh… Who knows, it might be worth it, but I’m too cheap.”

He set the tumbler down on the counter with a soft crystal “clunk.”

He picked up the Milton and opened it. He turned to the title page. It wasn’t 18th century. It was 1666. The year of the Great Fire in London. And it was signed, “Joannes Miltonius.”

He looked all around as if suspecting someone else was present.

Then he let out a huge exhalation.

“Wow… just wow…”

He looked more closely.

“I don’t recall this work or this imprint. Perhaps it was lost in the fire… I will need to brush up on my Latin to parse this all out. The title page must have a hundred words on it.”

He lifted the crystal and took a sip. The rye was so smooth it virtually evaporated upon his palate.

“Wow…” he repeated, staring at the book.

There was a bit of string dangling from the top edge about halfway in the text block. He pulled on it gently and an old-fashioned Christmas gift tag slid out.

Holly and ivy were engraved and hand-colored in the top left corner. The words “Merry Christmas” were written across the center. That was all.

“Wow…”

He set it down gently on the counter.

“This is indeed a stellar night you two.”

He had turned all the store lights off except those above the front counter. That light only reached a dozen or so feet down each aisle before giving way to blackness.

He turned and went into his office. He plucked the golden ring from its place hung by a pin above his desk. He rolled the plain round perfection between his thumb and forefinger.

“It’s a good life here and now,” he said, returning to the counter. He lifted the tumbler and took another little sip. “But it is Christmas Eve. Let’s see where we go this time.”

He slipped it onto his finger and whispered “Priscilla.”

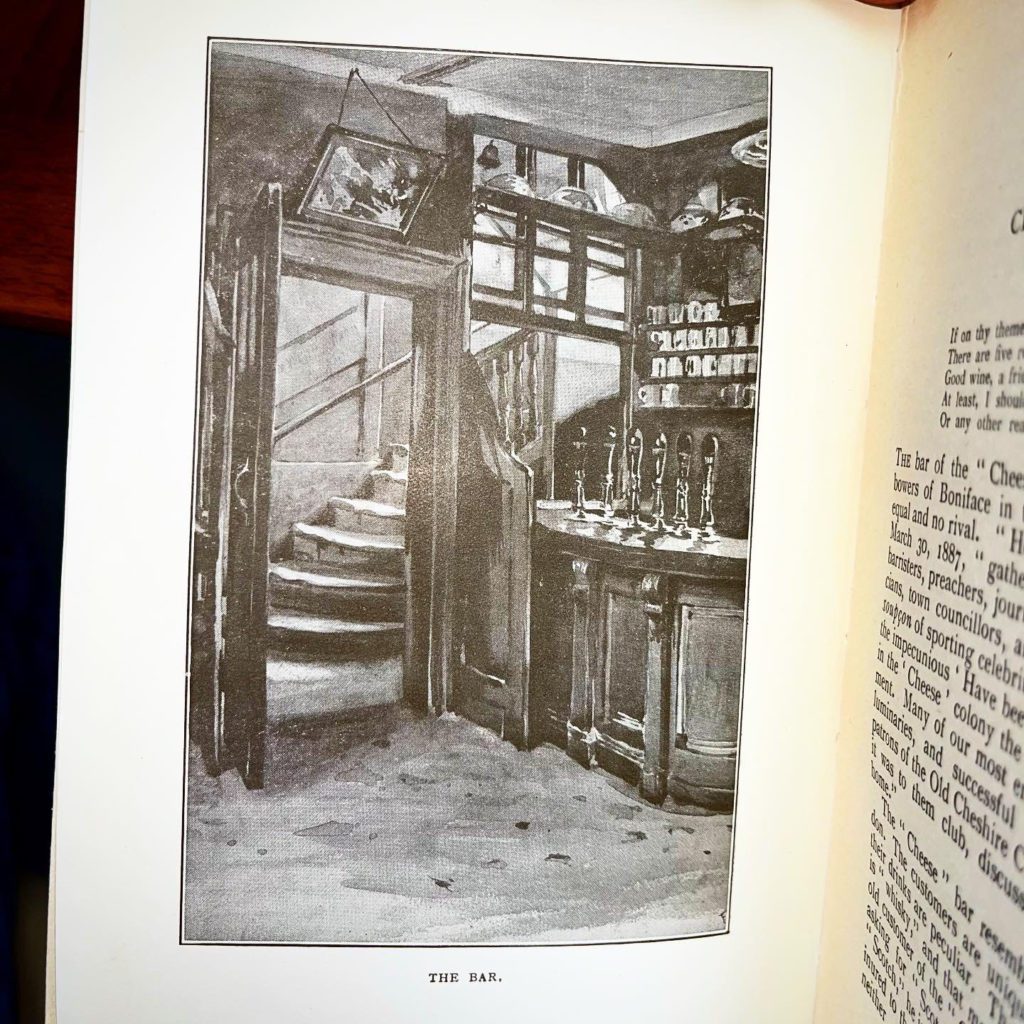

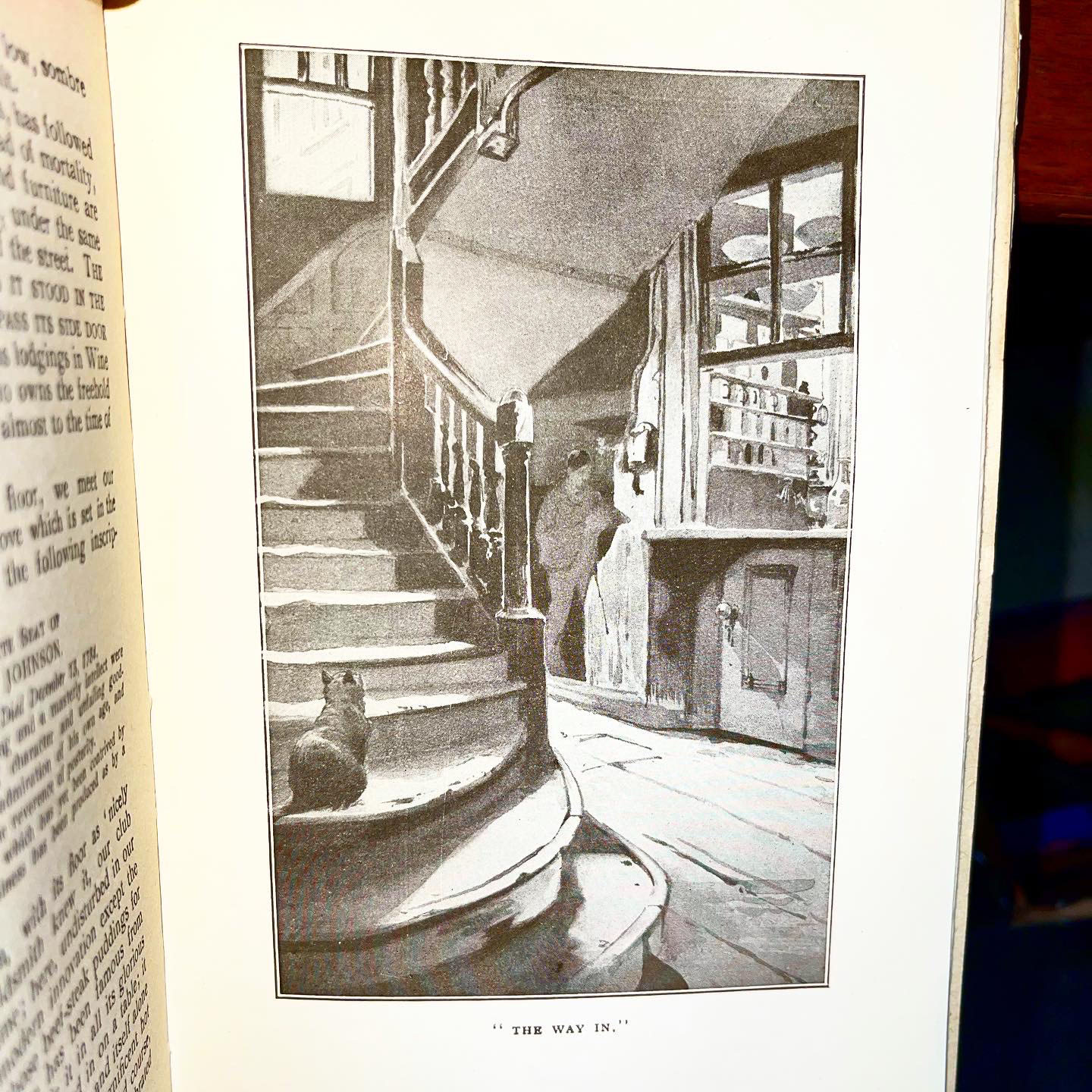

When he opened his eyes, he was in the Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese on Fleet Street in London. He was seated in the corner across from the glowing embers in the little fireplace in the ancient bar. It looked just the same as it had when he’d visited only a couple years before.

It also looked the same as it had several centuries before.

He was between two men. A large pewter goblet of ale was before each of them. On his left was a burly man wearing a white powdered wig. His face was scrofulous.

“Dr. Johnson…” he whispered in awe.

“Sir! HAVE we been introduced?!”

“Don’t be such a stickler, Sam,” said the other man seated on his right.

The bookseller turned and was only inches from the long goatee, long nose and bushy eyebrows of Charles Dickens.

“It is very well for you to write about all manner of rabble, Charles,” Johnson blustered. “That does not mean I must endure sitting next to one in my own corner of this ancient establishment. Why, I am told others have sat here quaffing the excellent ale in this room long before I was born.”

“Rabble? I am a keen observer of all manner of men. I would say this fellow looks decidedly bookish, Doctor.”

Johnson leaned in and squinted at the bookseller his bulbous and deeply pocked nose far too close for the bookseller’s comfort. Then he rose and went to the small fireplace. He turned and raised the tails of his coat to warm his backside.

“Perhaps. Perhaps. Well, explain yourself, sir! How came you to drop in between Dickens and myself? We were discussing neologues that perhaps should be added to my dictionary and suddenly… Well, there you are!”

The bookseller put his right thumb and first two fingers on the ring and slowly turned on his left ring finger.

“I didn’t know neologue was a word,” he offered meekly.

“Sir, if I say it is a word—then it IS a word!”

“Sam, let him be. He is no rabble,” Dickens sided with the newcomer. “But tell me how DID you come to be here?”

“I’ve visited Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese many times over the years. I’ve often wondered what it would be like to be here among great authors. But may I ask how you two come to be here at the same time? You… your lives never crossed paths, ummmm… chronologically.”

Dickens had produced a folded sheet of paper from a vest pocket and was scribbling frantically with a short pencil.

“Well, sir, we are here together because we are dead! And it IS Christmas. We walk abroad at such times and naturally this is a place that draws us.” Johnson stopped abruptly and looked down at the seated Dickens. “Why are you always scribbling and stuffing notes in to your pockets, sir?! I find it very distracting. Are you spying on me? Stealing my thoughts for your own work?”

“Why, no, Sam. I like to record things and people that interest me. And, indeed, I have worked many, many conversations and characters I have noted thusly in public into my work. One should always write what one knows, and I know people. And London. As for our visitor here, he is certainly not the first to have joined us. We have even had some who wear clothing similar to his—though not as shabby.”

“Are you not dead too, sir?” Johnson inquired full of curiosity.

“Not dead. At least not that I am aware of. It is this ring, you see.” The bookseller held up his left hand. The ring glowed warmly in the cozy firelight.

“It was given me by a… woman… a kind of muse, I think. When I put it on it takes me places. Once I found myself outside of the Globe Theatre on the night Mac… the Scottish Play was premiered. I don’t put it on often. Sometimes it takes me places I’d rather not see.”

“NOT dead, you say!?”

“Well, I have seen many things but never a magic ring.” Dickens changed the subject, ” I should like to write a story about a magic ring. Perhaps a Christmas story. But in my… ah… situation… I am, afraid there are no publishers in the afterlife. They all go to…”

“Sir! You have written plenty of Christmas stories already. And plenty of long books on London rabble. May I add, some VERY long.”

“I wish I had had time to finish Drood. You know, Sam, Drood was the only person to have ever…”

“Sir! Will you please stop scribbling! You are worse than that whoremonger Boswell! I cannot carry on a conversation with a man who is not paying attention to me.”

“Well, you could turn and face the fire, Sam,” he quipped. “And I AM paying attention. That is what I am recording. This has the makings of an interesting evening. And an interesting story.”

“THAT side of me is NOT cold, Charles!”

“Uhhh… someone has written a story about a magic ring,” the bookseller softly offered.

“Really! Never heard of such a thing.”

“Is it good? Do people buy the book?” Dickens was asking with a bit of authorly competitiveness in his tone.

“It is numerous books, and, oh, yes, it is very popular… ummm, where I come from, some say it is the best work of the 20th century. You’d like it, Mr. Dickens. It is very magical. I’m not sure Dr. Johnson would enjoy it though. Has Tolkien ever come here?” the bookseller asked hopefully.

“Talking!? That is all that goes on here, my dear sir! That and drinking. Which reminds me. Charles, I believe it is your round.”

“No. I am quite sure I purchased the last ales. And the two prior rounds as well. I have a note here…” He began fishing in various parts of his garments.

“Hellfire! You and your notes.”

“Tolkien. J.R.R. Tolkien. ‘Toll Keen.’ But he spent most his life in Oxford.”

“The philologist!” Johnson thought aloud. “I do believe he was here once. But he would not discuss words with me. He went on about dragons and elves and wizards. Dreary stuff. And I told him so.”

“Perhaps that is why he too has never returned,” Dickens said, hinting that Johnson had chased many spirits away.

“Well! You would not read anything like that. In fact, my dear fellow,” he addressed the bookseller with a false air of confidentiality. “Dickens here reads only his own work. I am sure he could not bear reading the greatest author of any century except his own. And that is because he believes HE is the great…”

“Why, Doctor, I take affront at that!”

“Gentlemen, gentlemen. Please. Let me get the next round… but I’m afraid I only have American money. And plastic.”

“What, sir, is ‘plastic’? It is not in my dictionary and is therefore not a word.”

“You may just start a tab with the Innkeeper. We all have tabs. Infinite tabs at that,” Dickens offered. He broke into a wide grin at his riposte—and perhaps the concept of free ale for eternity.

The bookseller rose and crossed to the bar which was only a few steps away.

“I’d like three pints of your finest, my dear fellow,” the bookseller addressed the whiskered man behind the bar.

He began pulling the handle back and forth pumping the cask ale into large pewter tankards.

“I do no belee I seen ye here afore, soor,” he said to the bookseller cordially.

“I’ve had many a pint here. Mostly in the 21st century.”

“You don’t say! The tavern is still here then?”

“Yes. And almost completely unchanged.”

“Aye, ‘s long as men are men they’ll ha’ thar ale.”

“Unfortunately, in my days, the beer most people like is pale and watery,” the bookseller complained.

He turned and carried the beer back to the low tables. He set them down carefully so as not spill a drop, though Johnson’s clothes were already quite stained and disheveled.

“What year is it?” he asked, sitting down.

“Sir. It is no year at all.”

“It is Christmas, my dear fellow. Christmas is timeless,” Dickens added.

“Well, how do you celebrate New Year’s Eve?”

“What did you say you did—back when you were alive?”

“I’m not dead yet. And I didn’t say.”

“Very well. Hmmph. The ring and all. What do you do when you are not quaffing bitter with dead writers?”

“I’m a bookseller.”

“Good! Hail fellow and well met!”

“Do you sell my books?” Dickens asked.

“Well, of course, and they are still quite popular. Classics. Some taught in school—or used to be. Although too many are not readers these days and opt for the movies and mini-series.”

“What. What! Speak English, sir! Not gibberish! Innkeeper, this fellow is ranting!”

“What is a ‘movies’?” Dickens asked seriously.

“Ummm… that is hard to explain. I suppose it is akin to a stage play… a play that is captured on film… ummm, captured like a painting in a gallery. But it is alive, and whole stories are told with it. Moving pictures! That’s it! The pictures move on a screen and tell a story. But it uses real people and voices and scenery. I suppose it would seem like magic to you two.”

“Pictures that move?! Indeed! Innkeeper, no more for him. He cannot hold his ale.”

“And sometimes people go to theaters, and these moving pictures are displayed on a large screen. The audience sits in seats in the dark and watches the story play out on the screen.”

“Are any of my stories told on screens?”

“Oh yes! Many! Why, A Christmas Carol has been made into many, many films—moving pictures—over the last century—er, my last century.”

“I say! I think I like that! Is there money for the author in these picture galleries?”

“Millions! That is if the author is alive or the heirs have kept up the copyright.”

“The right to copy?! Sir, my books are published by my order. No copying is permitted.”

“No, no copyright is a legal term. It is used to protect the author’s creation.”

“Well, I must be making a mint if Scrooge’s story is being made over and over.”

“Hrummph… what about my works?”

“Kinda hard to make a movie about a dictionary. But I’m sure Rasselas has been filmed by someone somewhere.”

“No millions for me, then?”

“You have a great reputation and occupy an important place in literary history. But I suppose it is Boswell’s Journals and his biography of you that accounts for most of your notoriety.”

“B, B, B, BOSWELL!!! He gets credit for my work!?”

“He wrote diaries and journals for decades. Many of them record your words and interactions and travels. Why, without Boswell, far fewer of your words and opinions would have been preserved.”

Johnson’s face became redder and redder. His nose more bulbous and veinous and bumpy.

“Sir, I published a great deal.”

“Indeed, you did, Dr. Johnson, but Boswell captured your genius in a day-to-day manner. Volumes of it!”

“Did they sell?”

“There were quite popular in the mid-20th century. Likely because of the circumstances in which there were discovered. In a trunk. In an attic. In Scotland. Just think, all that could have been lost had any relative over the centuries found them embarrassing to the family and destroyed them.”

“Hmmmppph! I imagine there is a great deal that would benefit mankind by their never seeing the light of day. “

“They are quite important works. They let us know many manners and conventions of your time.”

“And I’ll never see a tuppence.”

“Neither did he.”

“He just wrote down my words and became a famous author you say?”

“Well, there’s more to it than that.”

“Useful fellow for arranging trips and giving me a hand up into coaches. Could fetch some fine claret as well. And arrange gatherings.” He paused. “Dickens! You are scribbling again! Are you taking this down?”

“Yes. Perhaps I will be my own Boswell.”

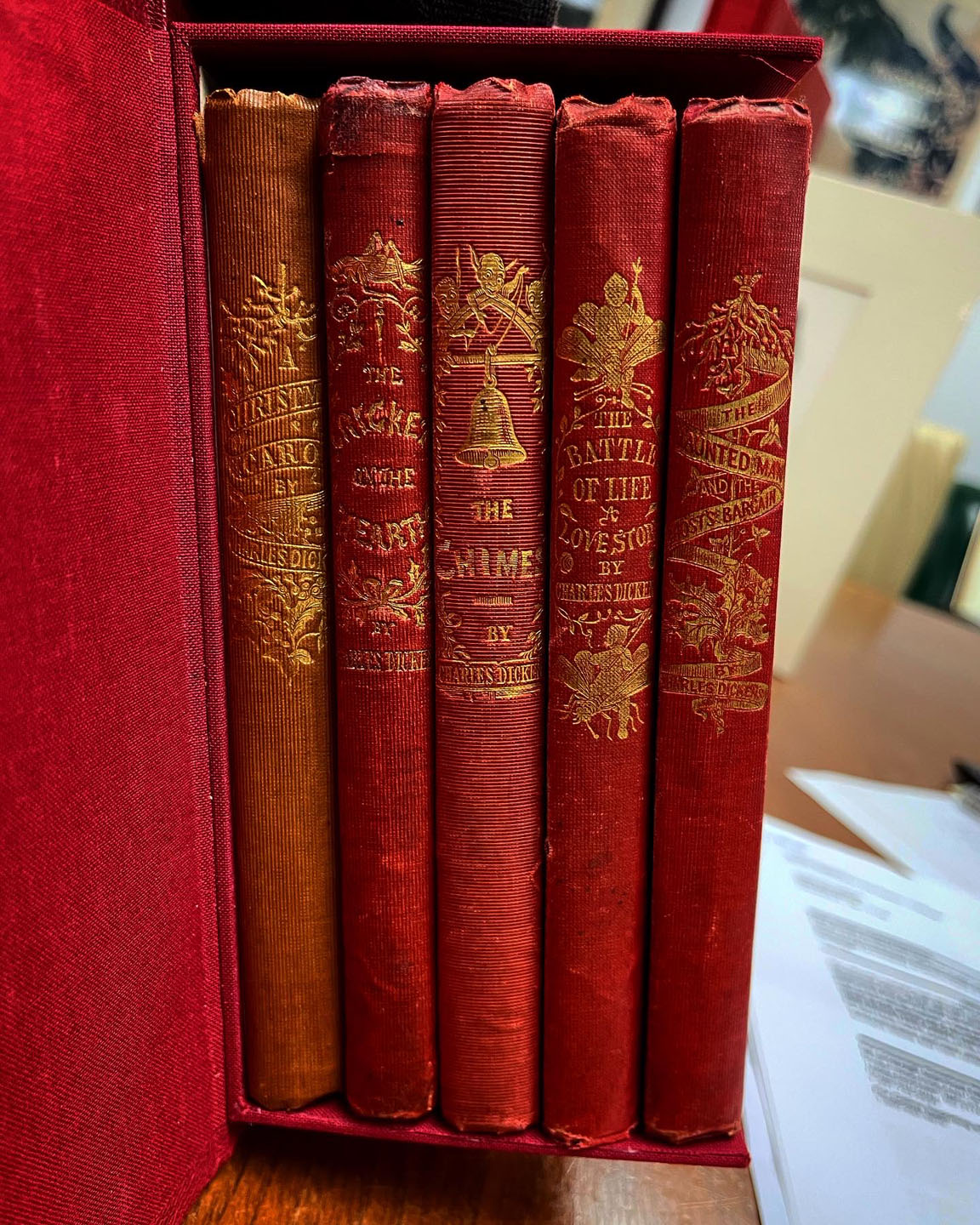

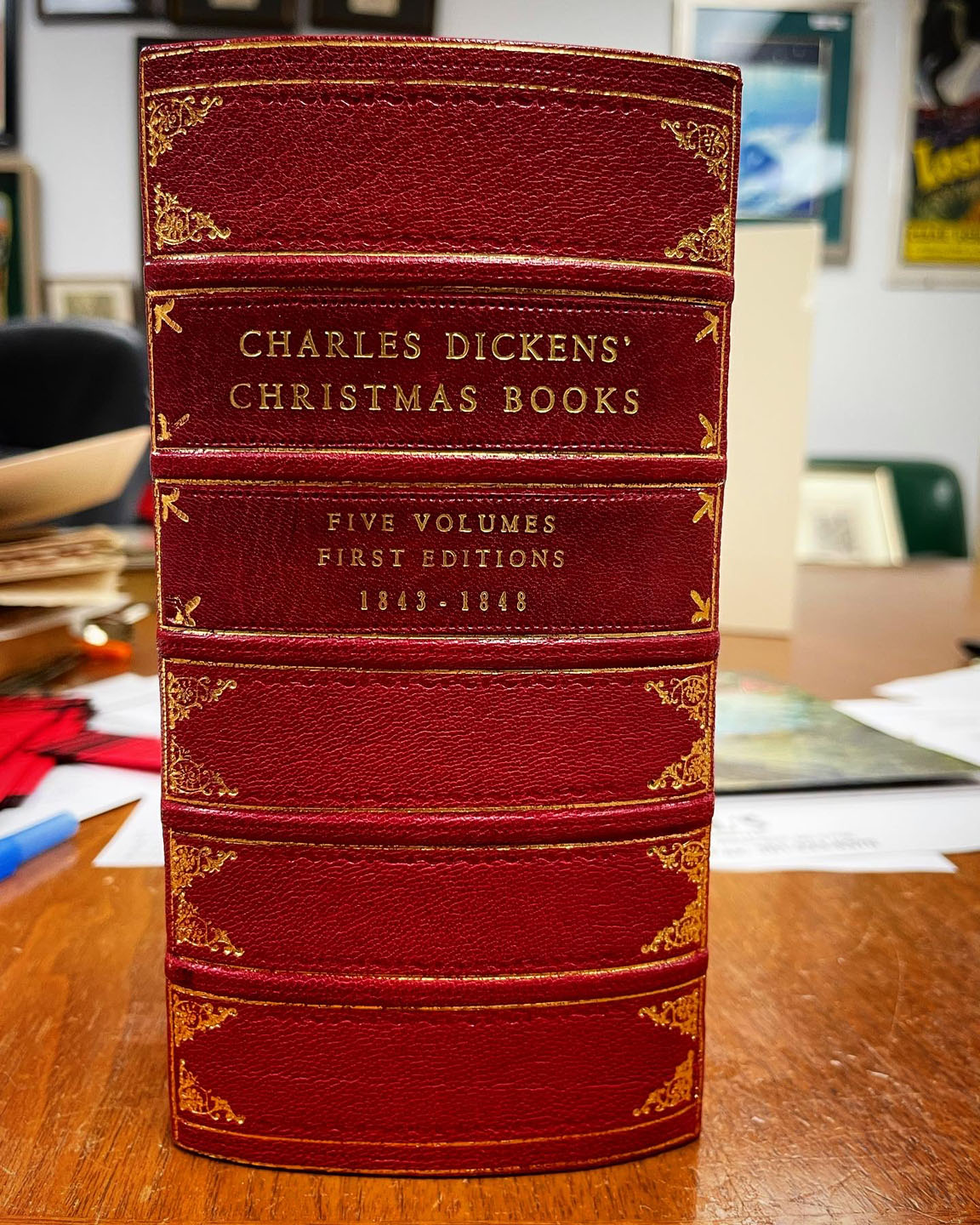

“Mr. Dickens, I have first editions of all your Christmas stories. I should very like to get them signed by you.”

“My dear fellow. Do drop by with them, and I will accommodate you in exchange for a flagon of our host’s best bitter.”

“I don’t know if I can find my way back.”

“Maybe when you are dead, sir!” Johnson guffawed at that and spluttered ale all over his cravat and coat.

There came some thumping and knocking and tap, tsp, tapping out in the hall which lead in (and out) from the entrance in the narrow alley.

A man was led in by a young woman. His eyes were milky with blindness. His hair was long and dark and parted in the middle. The young woman helped him to a seat across the room from the trio. She turned and departed demurely after whispering into the man’s ear.

“Yes, daughter. I will not,” he said toward her retreating figure.

“Milton,” Dickens confided quietly to the bookseller.

“No Latin today, if you please, John. Our guest here does not have any, I think. His speech is quite lazy. Poor syntax. I would say he has been taught by rabble. Street English. Alley English. HA! There I have coined another! Alley English! Ha! Ho! And he is not dead yet—so he claims. A seller of books from the distant future,” Johnson said by way of introduction.

“I’m not English. I’m American. And, yes, language has become quite casual in my time.” The bookseller paused. “Mr. Milton, I am quite honored to make your acquaintance.”

He started to rise as if to approach the man and perhaps shake his hand. Dickens caught hold of the tail of his coat—a rumpled tweed blazer with suede patches on the elbows. He gently tugged him back into his seat.

“He does not wish to be touched. Never has. Not since his wife died, and he was sought for arrest.”

“He is not dead yet? How can you tell? Does he not look dead? Do I look dead?” Milton asked flipping his long locks back over his shoulders.

The innkeeper approached him.

“I am jus’ setting a flagon afore ye, Mr. Milton soor.”

“John, you have never looked better. The prettiest writer in the English pantheon,” Dickens teased at his vanity.

“No, Mr. Milton, I am not dead—yet.”

“Why how came you here then—at this timeless place?”

“A ring brought me. I was given it, sir. By a muse, I believe. Though she has never admitted to it.”

“How did she look? Fair? Tall?” he asked excitedly.

“I’ve never seen her. She speaks to me when she is wont. Her accent is Irish, I believe. Though sometimes there’s a Welsh inflection to it.”

“Never seen her? How gave you this ring did she?”

“That’s a long story… ummm, but there are times I think I may have been in her presence…” the bookseller mumbled.

“Speak up, fellow. I am blind but not deaf. I find it hard enough to understand your speech when you actually annunciate.”

“Occasionally… I… I… encounter women—often at my bookshop. They always appear different—age and size and looks—But… but… their eyes. They change color. Green, turquoise, amber… I… I often suspect these women may be her—in disguise.”

“Her eyes change color. Are you sure? Dickens, how many ales has this fellow had?” Milton inquired.

“He is still on his first. He appears to be a talker and not a drinker.”

“And you have a ring she gave you, but you have never seen her.”

“It was left to me. Along with an ancient note written on vellum. It was in a script and language I couldn’t decipher. But as I stared at it, the lines shifted, and I was able to read them. The note said the ring was mine.”

“You are sure these women have eyes which change color?”

“Yes. Perhaps a dozen or more over the years. I don’t keep track.”

“This ring, may I hold it?”

“If I removed it, Mr. Milton, I believe I would disappear—back to my own time. But if you’d like, you can touch it upon my finger.”

“Touch? Touch? No, I do not like touching nor being touched. Not since she died—’My late espouse’d saint,'” Milton said choking back a sob.

“That is my favorite sonnet of all time Mr. Milton.

‘And such as yet once more I trust to have

Full sight of her in heaven without restraint,

Came vested all in white, pure as her mind:

Her face was veiled, yet to my fancied sight

Love, sweetness, goodness in her person shined

So clear, as in no face with more delight.

But O, as to embrace me she inclined,

I waked, she fled, and day brought back my night.'”

“Ah, you have a copy of my verse?”

“I have many copies of many of your books. In many editions—sadly only a few are first editions.”

“Does that matter to you?”

“Yes. First editions are a big deal to modern booksellers.”

“Big ‘deal’?”

“Ummm… They’re sometimes considered important and valuable. I just this evening came across a book of yours that I had never heard of before. It was printed in London in 1666. The title page was all in Latin, and I haven’t had time to parse it out. Perhaps the printing was lost in the fire?”

“Burned, yes. But not by accident. Some of my opinions on unlicensed printing and freedom of thought and expression were not popular. It was seized and destroyed—but for one copy. My own working copy.”

“You did not try to have it printed again?”

“No. I was warned. Threatened actually. I could not bear prison being blind and ill. I am glad you discovered that sole survivor. Perhaps you can have it printed in your own time. Is the press free when you live?”

“Free. But not free,” the bookseller said quietly.

“I do wish you would not mumble so.” Milton sipped his ale holding the pewter flagon with both hands. “Perhaps, perhaps—I should like to touch this ring. If it is really hers, I should… I have nothing that was hers. All gone. Taken away.”

The bookseller rose and crossed to the seated poet.

“I am taking you by the wrist, sir. Please extend your finger, and I shall put my ring finger to it.”

He did so. Milton did so. And the bookseller did so.

“Oh!! It is very hot!”

But he did not take his finger away. He pressed it more firmly.

“Oh!! It is she! I see her. Here before me.”

He raised his other hand high above his shoulder and stretched it as far as he could reach.

“Poor fellow,” Dickens spoke sotto voce.

“Can you not behold her? An angel with wings white as snow.”

“We see nothing, John. Perhaps the apparition is meant for your eyes alone,” Johnson spoke softly—for once sounding human and not a bluff fellow.

After a few moments, Milton removed his finger from the ring.

“She is gone. And I am blind anew.” He sighed deeply. “Thank you, sir,” he said to the bookseller.

“Can you tell me what she looked like, Mr. Milton?”

“A beauty of the heart and face and soul that only a real poet could describe,” Milton spoke softly, dreamily. “Her eyes were golden. No sky blue. No…”

“Well, sir! That ring of yours is quite a special object,” Johnson said.

“Indeed. I should like to write a Christmas story about it,” Dickens added.

“Let us talk about books and writing. I feel very merry this evening,” Milton said brightly. A smile spread across his face, and his blank white eyes opened wide. He raised the goblet to his lips and sipped deeply.

“Well, I know a bit about books but not writing,” the booksellers said.

“Talk about what you know my dear fellow. And if you ever start to write—write about what you know,” Dickens said, scribbling rapidly on a slip of paper. “And do drink up. You have come a long way, and your thirst should be whetted. You will find no other ale like this in eternity.”

“I am ready for another round. John, are you buying?” Johnson spoke all jolly. “He has never bought a round save his own in centuries,” he whispered close to the bookseller’s ear. His breath was quite malodorous.

“I shall, dear Samuel,” Milton said happily. “It is Christmas Eve, and we are all together. Four bookmen of different ages. Innkeeper. Four pints, and put it my score, if you please.” He turned his head in the direction of the other three. “Tell me, sir—you have not given us your name—what are books like in the far future.”

“They are much as when you all three were writing. Paper. Pages. Bindings—those are now mostly in paper covered boards. But occasionally they are bound in cloth—buckram or leather. Fine bookbinders even use vellum upon occasion.”

“Ah, that is grand to hear,” Dickens said.

“It would be a sad future if there were no books, sir!”

“A paradise lost,” Milton added and smiled coyly.

Johnson guffawed and ale spewed all over himself, Dickens and the bookseller. “I say, John! You must have the Christmas spirit with you this evening. I thought your sense of humor lost long, long ago.”

“It must have been the Christmas ghost that was just visited upon him,” Dickens added.

And the men conversed and laughed and drank. And drank. And drank.

When the tall clock out in the hallway chimed 11 times, the bookseller came to attention.

“It is nearly Christmas. I must get back to the shop! Merry Christmas to you all, fine fellows. Merry Christmas to us all and to all a good night!” He paused, holding the ring between his right thumb and forefinger. “God bless us every one.”

With that, he slipped off the ring and disappeared.

“He stole my line!” Dickens said faking effrontery.

“He left this ‘ere green paper ‘neath ‘is flagon,” the innkeeper said crossing the room to deliver three more ales and retrieving the bookseller’s empty. “There’s a number ’20’ on each corner—tho’ I’ve no idea whose portrait is upon it!”

“Charles! You have pilfered thousands of lines. Including many of mine.”

“And mine,” Milton added.

“Speaking of pilferage, my dear doctor, have we ever discussed certain similarities between Rasselas and Voltaire’s Candide?”

“Sir! Have you ever asked which came first, the chicken or the egg!?”

“Gentlemen, gentlemen, please. It is Christmas Eve, and I’ll be saying ‘last call’ ere long. Save yer battles for another evening and be of good cheer. Christmas comes here but once a year.”

The bookseller was back behind his sales counter. Long dark aisles of books stretched before him. The ring was held between his right thumb and forefinger. He set it down. It rolled on its edge a couple of inches and then toppled rattling round and round. It made that dull metal sound that only gold can make.

Mathilda thumped down from her perch, crossed the counter and rubbed a whiskered cheek against his hand.

Setanta scrabbled around from the front. He raised himself on his hind legs and set his front paws upon the counter. He had a thin volume in his mouth. He set that on the counter and then gave the bookseller’s ear a big wet lick.

“Well, I’m back.”

He picked up the book and was surprised it was perfectly dry. He wondered how the dog, who was quite a slobberer, could do this.

The bottle of A Midwinter’s Night Dram was before him as was the empty tumbler. He poured two fingers in and took a small sip.

“You can’t drink your dram and have it too,” he told the cat and dog. “But nothing lasts forever—except perhaps books.”

He picked up the book and opened it.

“Twas the night before Christmas

Not a creature was stirring

Not even a mouse…”

Mathilda gave a low rumbling growl.

The ring glowed softly between the bottle and the glass.

There are no comments to display.