“A UNESCO conference in 1964 attempted to define a book for library purposes as “a non-periodical printed publication of at least forty-nine pages, exclusive of cover pages.”[2] A single sheet within a codex book is a leaf, and each side of a leaf is a page. Writing or images can be printed or drawn on a book’s pages.”

“Using “leaves” and “pages” as if they were interchangeable. They’re not. Confusing leaves for pages when you’re requesting an estimate could result in a bid that’s way off. For example, a mechanically-bound book with 128 pages consists of 64 leaves (sheets.)”

Often when we get a book that is falling apart we describe it as:

“Loved to pieces.”

This is a true description most often with children’s books. I believe I still have my copy of Peter Rabbit which was read to me so often as an infant and toddler I had it memorized and could recite it as I turned the pages—pretending to “read” them as I did. Eventually the binding split then chipped and torn pages began separating from the binding. I “loved” that book. I still do. I hope I come across it before I have grandkids. It would certainly evoke the soft warm days of early childhood wedged between my parents in their bed on a Saturday morning or upon one of their laps in the rocking chair. It is, of course, worthless to anyone else.

Books that are simply worn out from overuse like library books or reference books I would not classify as “loved to pieces.”

What do we do at Wonder Book when books come in that are in pieces or incomplete or otherwise so damaged they are unsalable?

Salvage!

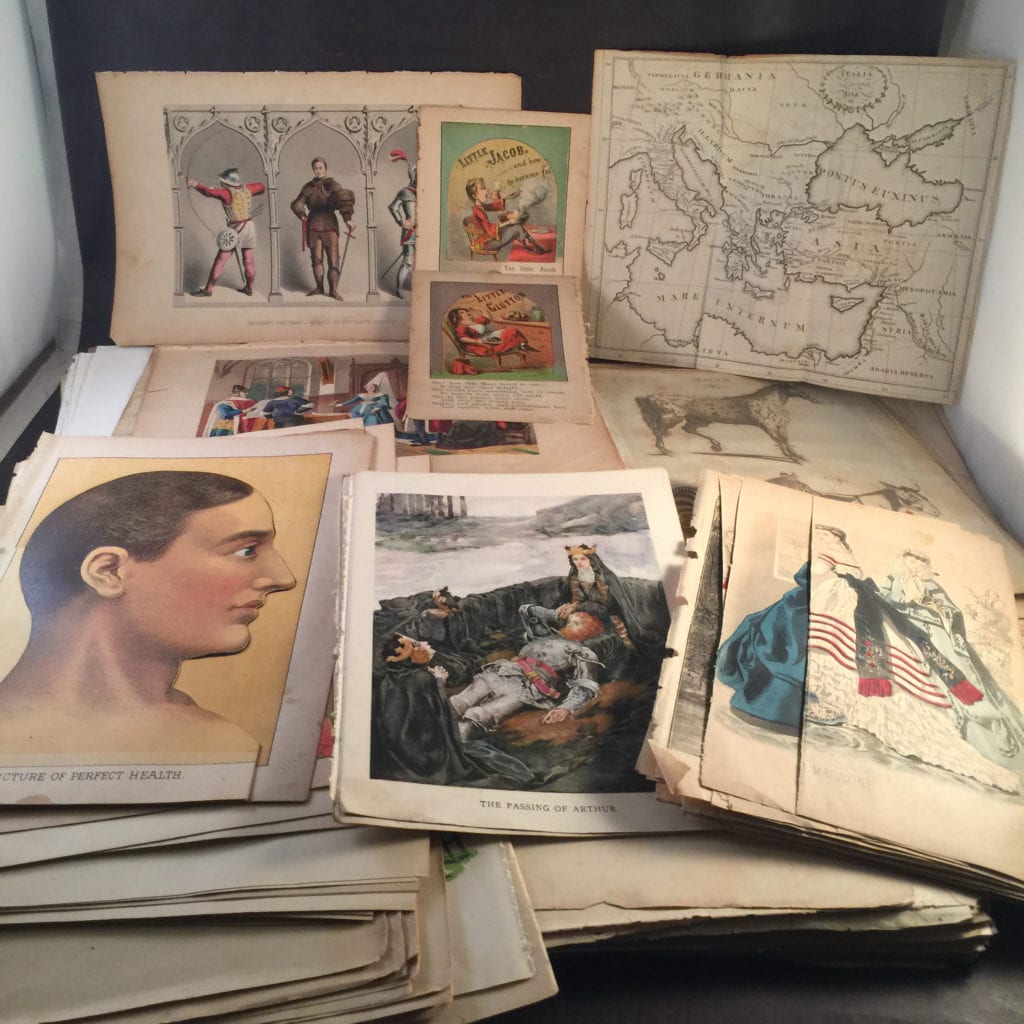

Our stores have 1000s of engravings, maps, illustrations, ephemera…carefully removed and “rescued” from books so broken there is nothing left but to recycle it for pulp paper—AFTER we’ve saved what we can. We call much of this “Bag and Hang.” We put these “leaves” in boxes and mark them to go to one of the stores. For example a box side marked: “WG B&H $2.95” would translate to:

WG—Wonder Book Gaithersburg

B&H—Bag and hang—these items should be placed in bags for their protection and pinned up to a blank wall or bookcase end cap for display.

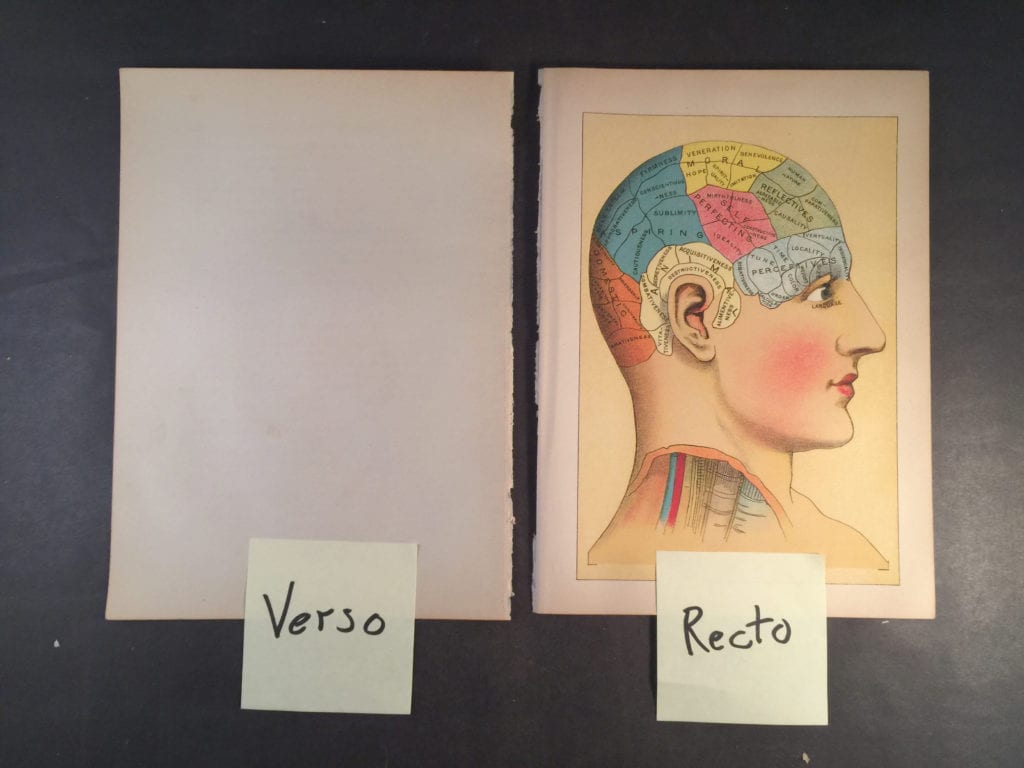

$2.95—the amount the items in that box should be stickered. Staff is trained to place stickers in an unobtrusive and non defacing way. Usually on back corner or “verso” of a plate. A plate often refers to illustrations bound into books using different paper and having an engraving or print only on one side of the page. The recto is (almost always) the side of the page with an image on it.

Easier to show than to explain:

We put very low prices on almost all of these salvaged illustrations in hopes that people will collect and/or display them at home or in their dorm rooms or as part of re-purposed artwork or crafting.

Customers can acquire some beautiful antique images executed via steel engravings or stone lithographs or copperplate or… They can be old or very old or sometimes very, very old.

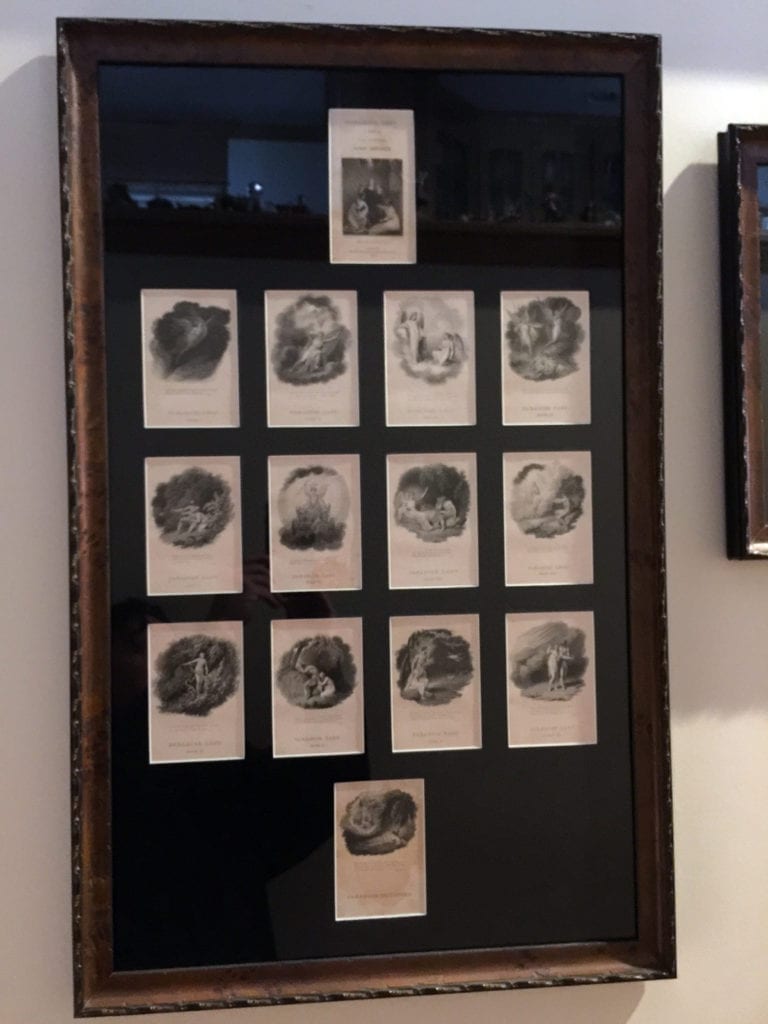

Many are “suitable for framing.” I’ve done it myself!

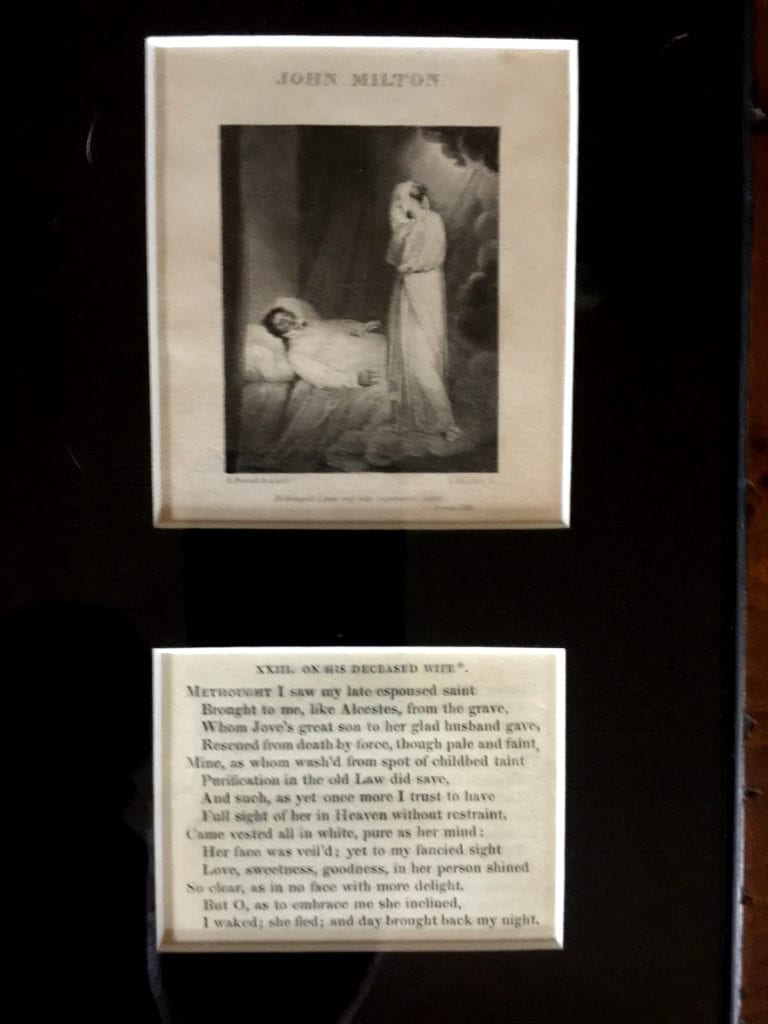

For my own use I salvaged miniature plates from a late 18th century set of John Milton’s works. The set was missing covers and pages and was battered and broken. Its only hope was for our Books By the Foot program. Removing the engravings would not harm the value of these whose next users would be designers staging them for appearances only.

I was thrilled to find there was a plate for Milton’s Sonnet XXIII—on his deceased wife. It is my favorite, and if I recall, I wept when my college professor, Gerda Teranow, recited it to our English lit class.

“…I waked; she fled; and day brought back my night.”

“…my night.”—Milton was blind he composed this poem.

The title of this story is “Leaves of Gold.” Here I am extolling the extremely low price we put on most salvaged images and maps and teasing the reader with the word “gold.”

Indeed, some leaves—salvaged pages—are worth far more than their weight in gold.

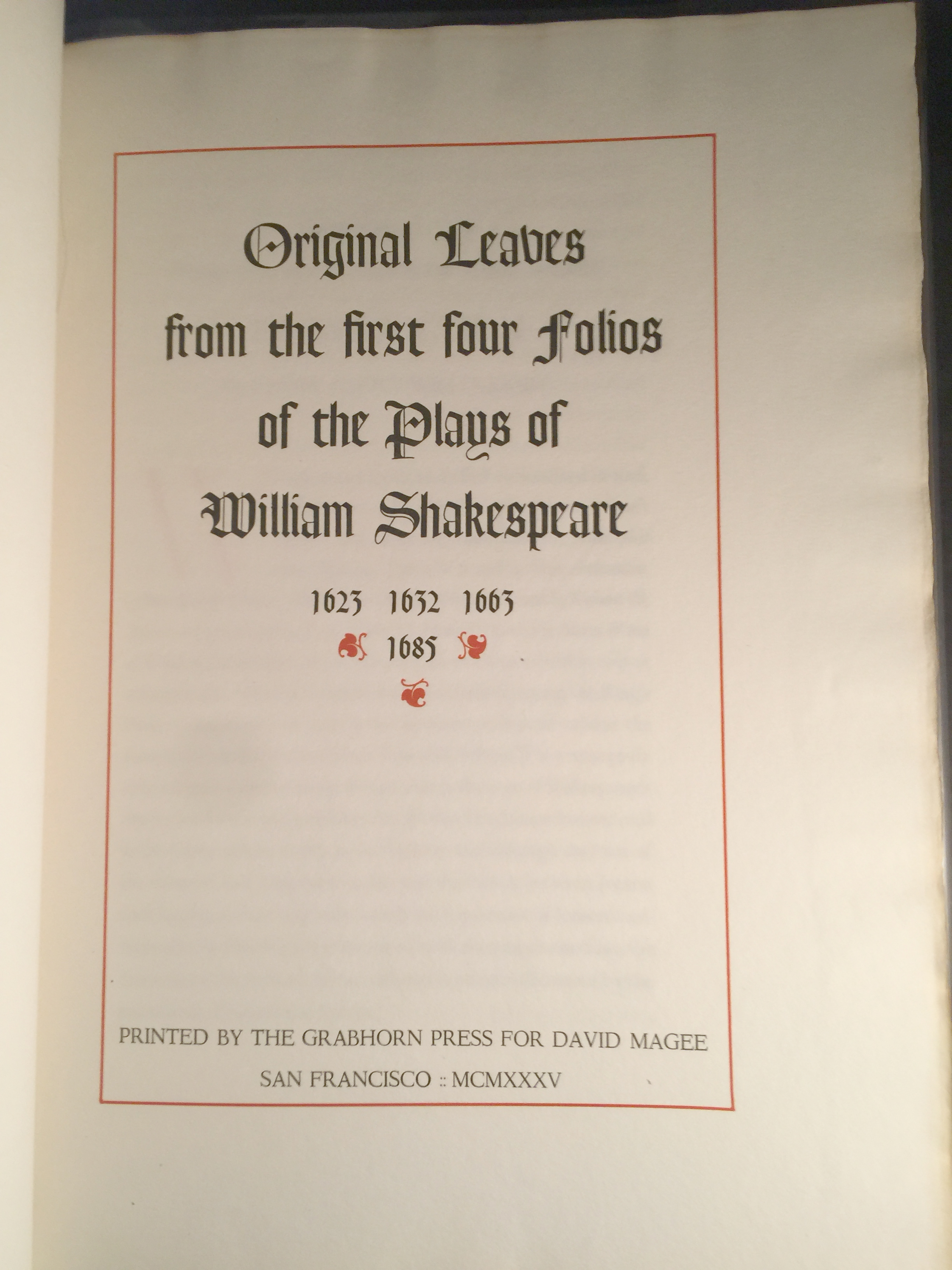

I’ve had a dream to own a First Folio of Shakespeare’s works published 1623. Not likely. The last one sold at Christie’s in 2016 for over $2.7 million dollars. But that was a bargain compared to a copy sold by Sotheby’s in 2006 for $5 million. The sale at Christie’s in 2016 also included the 3 later Folios (2nd 1632 $285,000, 3rd 1664 $531,000, 4th 1685 $69,000.)

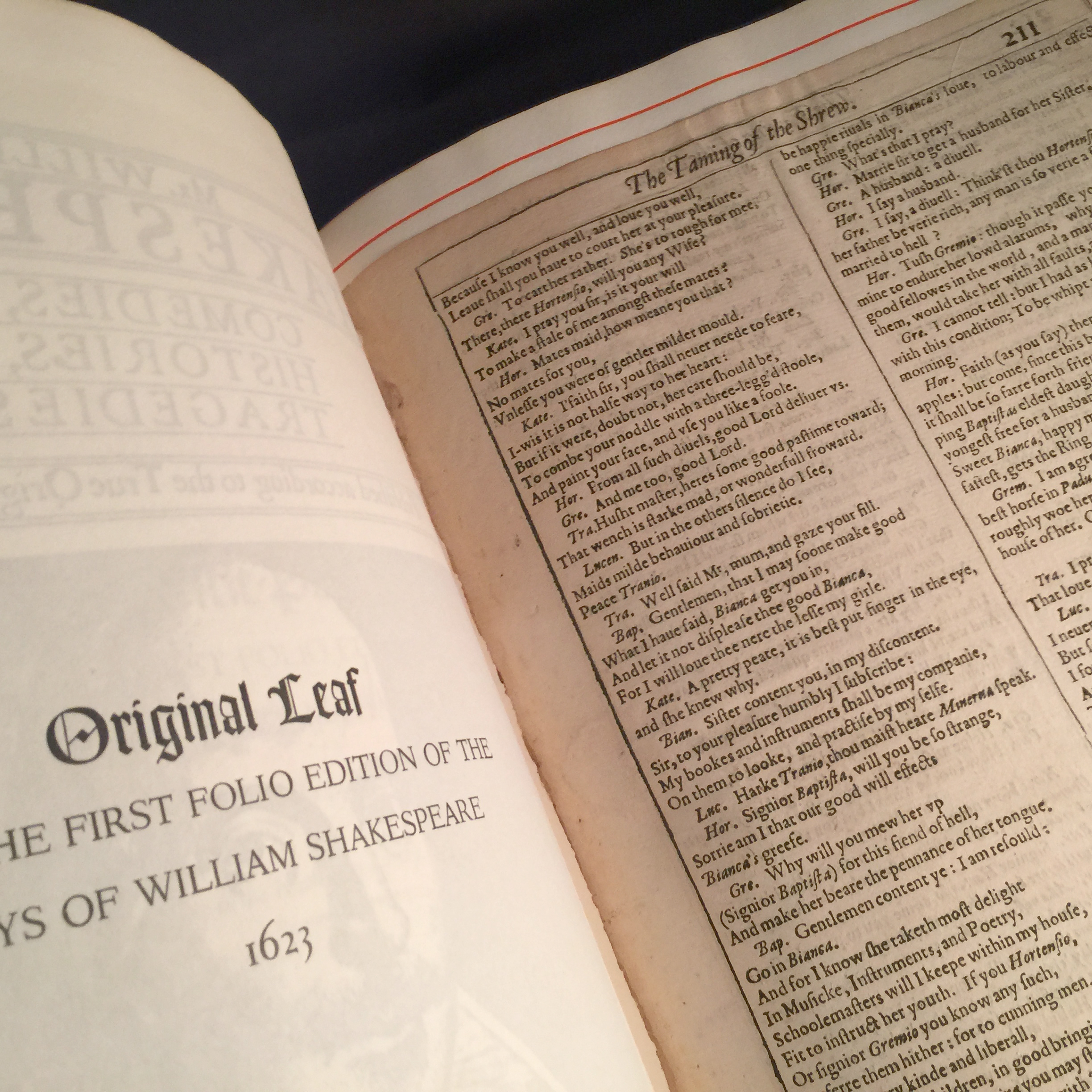

What’s the big deal about the First Folio? It was published some seven years after his death. A number of his works were published during his lifetime but most of those were flawed, or incomplete versions. Friends decided to help set the record straight and record all of his plays in versions they felt were the closest to how they had been written and performed. The two main compilers of the First Folio would know. They were members of the King’s Men—the troupe which performed Shakespeare’s plays. Without these two (Heminges and Condell), not only would have only 18 of his plays have survived in often dubious forms, but 18 others would not have survived at all. They added the following plays which had never been printed before:

Macbeth, The Tempest, Two Gentlemen of Verona, Measure for Measure, A Comedy of Errors, As You Like It, The Taming of the Shrew, All’s Well That Ends Well, Twelfth Night, Winter’s Tale, King John, Henry VI Part I, Henry VIII, Coriolanus, Timon of Athens, Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra, and Cymbeline.

No First Folio, no Macbeth.

So that’s a pretty important book!

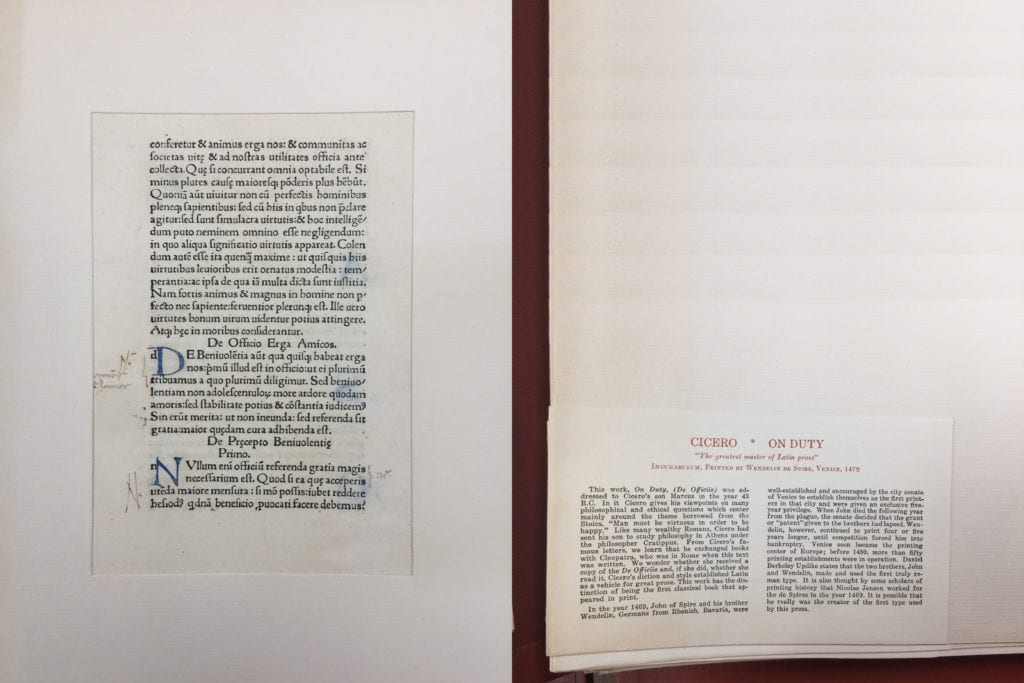

This is where we enter the world of rare leaves and leaf books. Some years ago I was offered a publication which included one original “leaf” from each of the first four folios. It was expensive, but I felt this would be about as close as I could get to Shakespeare and so I shakily wrote a check. I’m glad I did. It is one of my favorite “books.” I look at it often and (gently, with clean hands) touch the original pages and feel a connection to Shakespeare nearly 400 years ago.

What’s the story behind these salvaged pages? Likely booksellers had come across incomplete and/or heavily damaged copies of the first four folios sometime before this was put together in 1935. No one would purchase bits and pieces of these books. So they came up with the idea of offering a chance to own one page of each of the first folios. I have seen and acquired complete plays extracted from defective later folios bound separately. I imagine a complete play rescued from the First Folio would be extremely expensive.

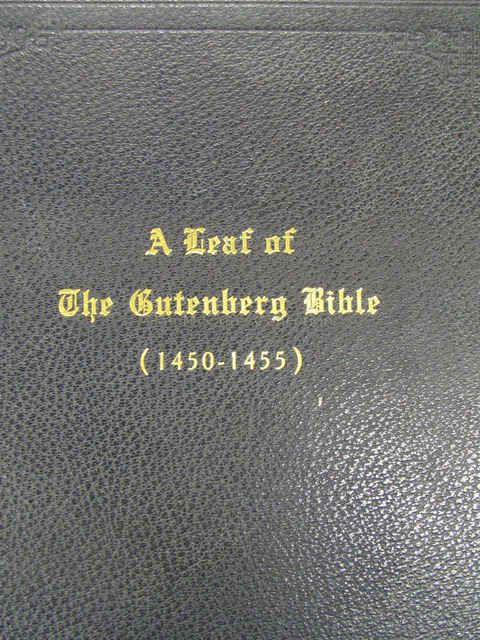

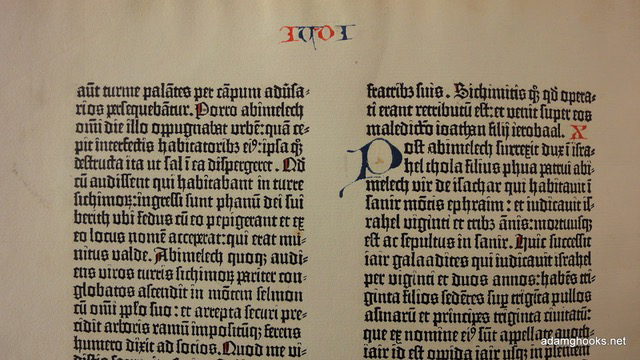

What else is on my bucket list? Well, the Gutenberg Bible of course. I regret passing on the single page I was offered nearly 10 years ago. It was unaffordable to me. Today I could pick one up now for a mere $90,000 via Via Libri—the fine online book search engine. That’s a bit of money for a single printed page! (Search “Gutenberg Noble Fragment” as “Keywords”.) So, I’ll likely never own even a single piece the first Western book printed using the movable-type printing press. That achievement changed the dissemination of knowledge and reading forever.

So, I’ve become a bit of a leaf collector. When I see a rare bit of something offered for sale that is unattainable in its complete book form I’m sometimes willing to settle for a single page—a leaf.

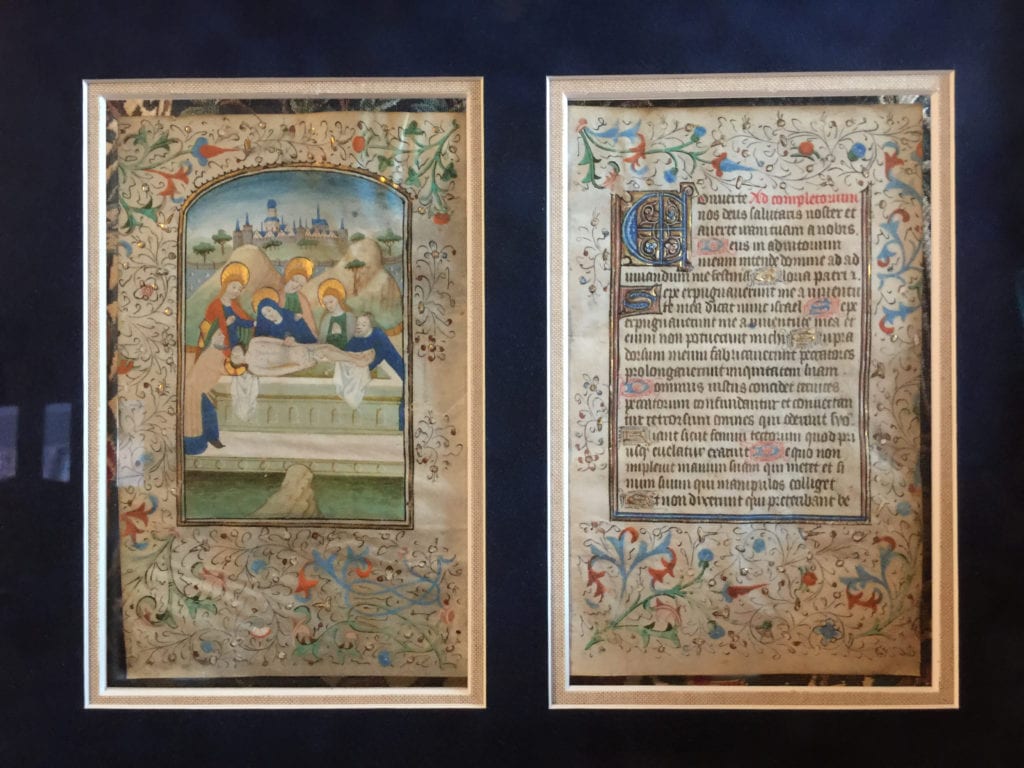

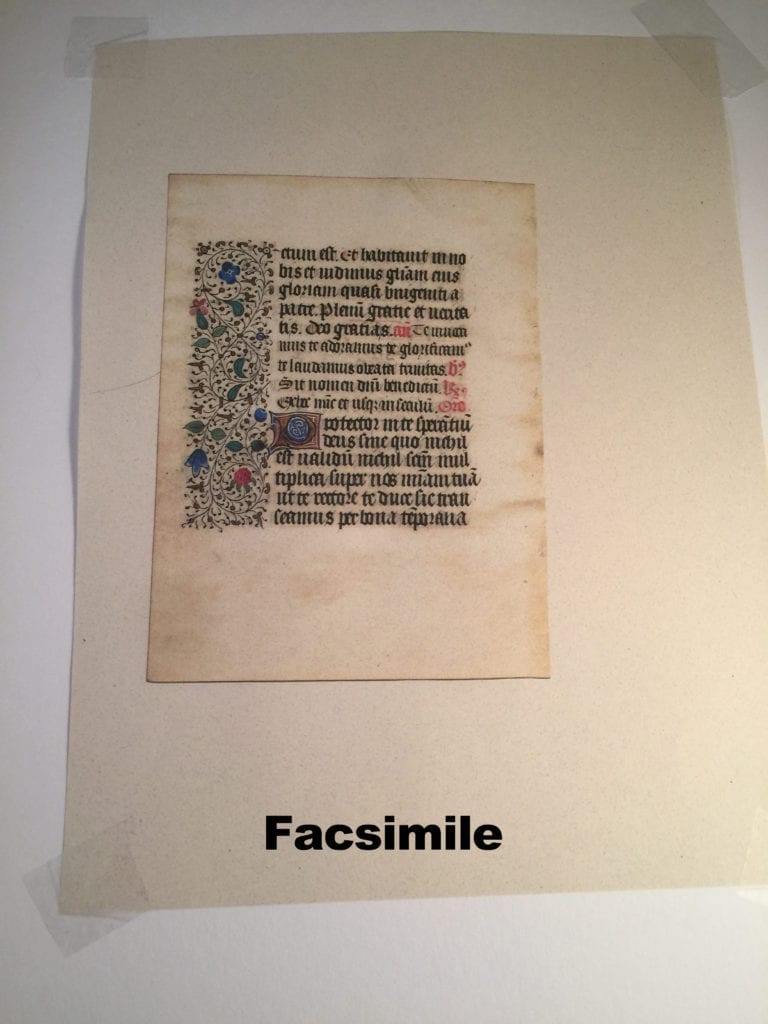

I’ve acquired some leaves from ancient illuminated manuscripts. These can transport me further back in time. They are beautiful bits of artwork drawn and painted (or illuminated) by hand. Those that speak most to my heart were done by monks in Europe before Gutenberg and his movable-type printing press. These are often executed on leaves of vellum. Wealthy patrons would commission these “books.” Often they were religious in nature—prayer books, devotionals, books of hours.

This leads us to some dirty business. “Book breaking.” That is the intentional destruction of a complete book for its parts. To me there is something unholy about this practice. There have always been those willing to cut out valuable pages or prints from complete books in libraries. This is out-and-out theft. The willingness to destroy a complete book because a print or map or specialist bookseller feels the value of the parts might outweigh the value of the whole is not the kind of thing I’d be willing to touch. Even if you own the book in question and are completely within your rights to cut it up…well, that’s not something I’d be part of (or knowingly acquire.)

Here’s what Wikipedia has to say about Book Breaking:

Bookbreaking is the longstanding practice of removing pages (especially those containing maps or illustrations) from books, especially from rare books. Bookbreaking is most often motivated by a market situation in which the maps or illustrations in a book will have more value sold separately than the value of the intact book. Often this happens because book collectors judge minor defects in an old book so harshly as to make them seemingly unsaleable. This widespread practice probably peaked in the 1970s or 1980s, because the price for old engravings and especially for old maps was outstripping that of rare books. However—in part because so many rare, illustrated books were “broken” in this manner—the price of the intact books has now risen the point where an old book is typically worth more intact. Book collectors have also become more sophisticated in understanding minor condition problems.

“Leaf removal”—it is not funny:

We’ve had a few thieves at the bookstores over the years. Fortunately most book lovers are upright and respectable and honest. A couple years ago we discovered someone was removing autographed pages from books in our open stock at one of the stores. Customers began bringing books to the counter and telling us:

“This book is labeled ‘Autographed’ but I don’t see a signature.”

Upon close inspection it was clear someone with a razor or box cutter had sliced out the signed page. I recall with regret a nice copy of Robert McCloskey’s Make Way For Ducklings had its front endpaper cut out. That was a $350 book. After the thievery that book was only a reading copy—worth only a few dollars. Other books began appearing with signed pages excised including The Art of the Deal by Donald Trump. It was signed on the title page. With the title page stolen the book was practically worthless. So, we began putting somewhat valuable autographed books either locked in our glass cases or close to the sales counter where we could keep an eye on them. I hope whoever was doing this has shame at some point and doesn’t profit from their actions. The thefts seem to have ended due to the measures we took.

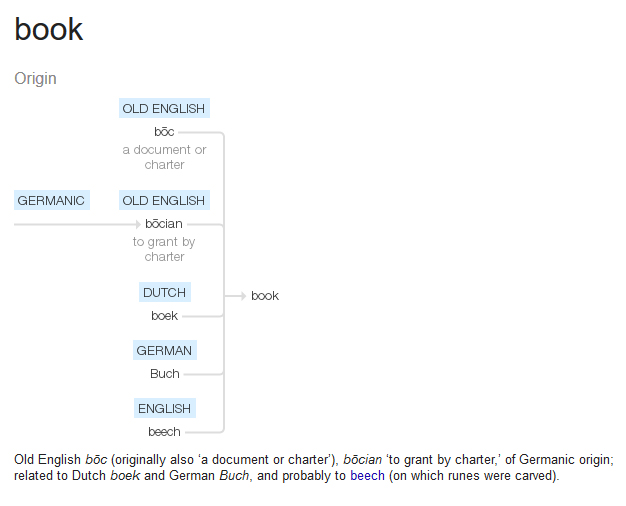

All this has gotten me to thinking. Why are pages called “leaves”? I don’t feel a stack of pieces of paper bound between the covers of a book look like a stack of leaves. Nor have I ever seen tree leaves stacked up in any manner evoking a “book.” There are etymological opinions that the word “book” is descended from the early or Proto-Germanic word for Beech tree. I’d like to think that maybe there’s an etymological link to tree and leaf (“book and “page.”) A romantic notion. Most likely the OED (Oxford English dictionary) has some etymological scholarship and opinions on those points. But if scholars can’t agree that “book” is descended from “beech” then I feel I can speculate (or dream) in my own amateurish way about trees and leaves.

For example Etymology Online states:

Old English boc “book, writing, written document,” generally referred (despite phonetic difficulties) to Proto-Germanic *bokiz “beech” (source also of German Buch “book” Buche “beech;” see beech,) the notion being of beechwood tablets on which runes were inscribed; but it may be from the tree itself (people still carve initials in them.)

Whereas another online sources muddies the waters (and covers their bets) thus:

Yikes! Is that hedging the etymological bet or what?

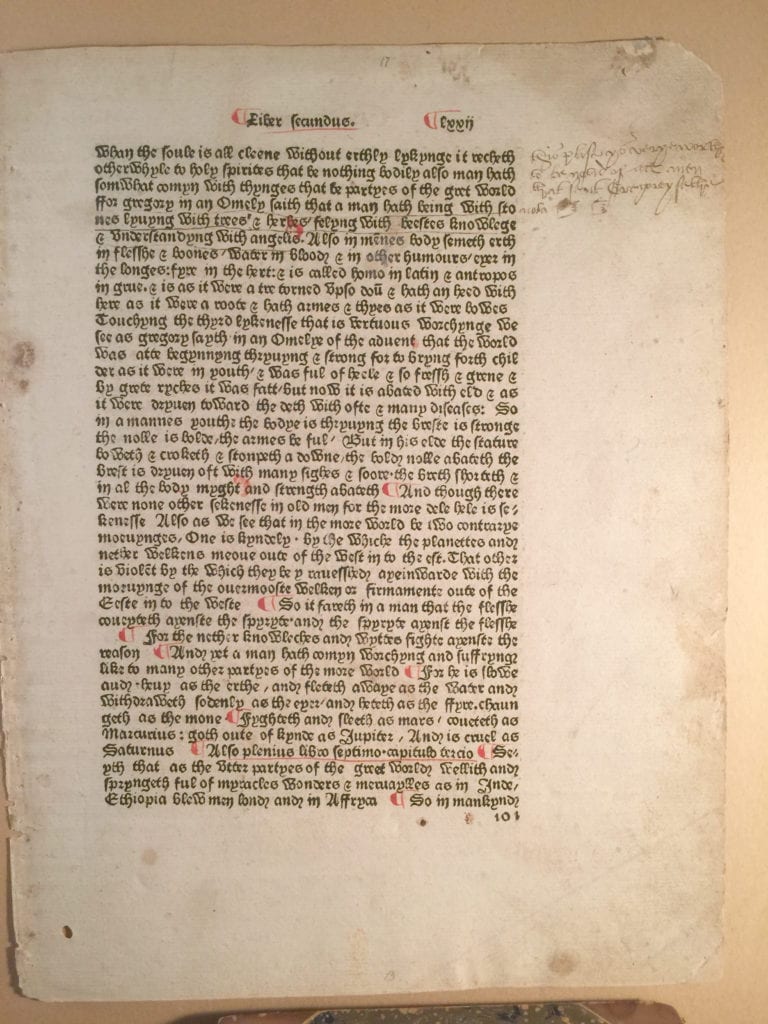

How many leaves have I collected? A bunch. Beside bound ones (or “Leaf Books”) I’ve also acquired some loose leaves. Here’s a Caxton leaf. William Caxton is thought to be the first to introduce a printing press in England. Complete Caxton books are virtually unattainable so I’ll just have to settle for this.

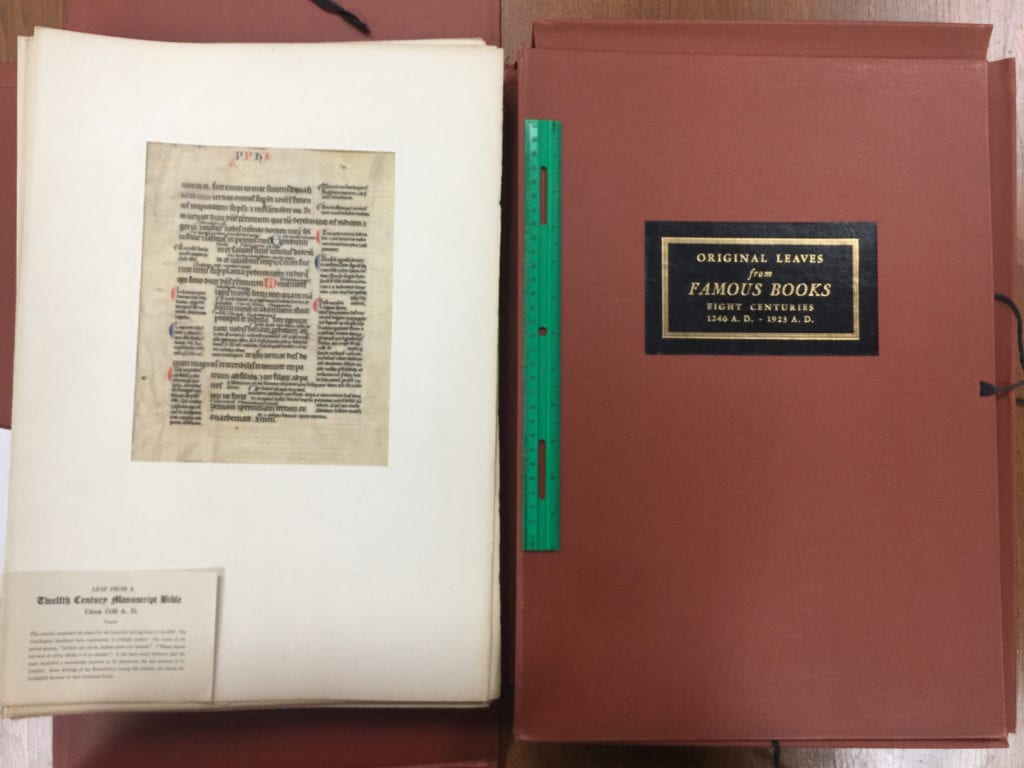

Recently my “leaf collection” was greatly enhanced by a windfall (hehe.) A colleague offered me two of Otto Ege’s leaf portfolios. Ege was controversial for creating these. Here’s what Wikipedia says about him:

Otto F. Ege (1888—1951)[1] was a teacher, lecturer, bookseller, and well-known book-breaker. He worked for many years at the Cleveland Institute of Art where he served as Chair of the Department of Teacher Training,[2] instructor of Lettering, Layout, and Typography,[2] and Dean.[1] He was also employed by the School of Library Science at Case Western Reserve University as a lecturer on the History of the Book,[1] and instructor of History and Art of the Book.[2]

Otto Ege’s greatest fame, however, came as a result of his book-breaking. Over a period of decades in the early 20th century, Ege systematically removed the pages of some 50 illuminated medieval manuscripts,[1] and divided them into 40 unique compilation boxes,[3] commonly referred to as “Otto Ege Portfolios.” These portfolios were in turn sold and distributed world wide.[3] Although strong profits were made from each sale, Ege defended his actions by stating, “Surely to allow a thousand people ‘to have and to hold’ an original manuscript leaf, and to get a thrill and understanding that comes only from actual and frequent contact with these art heritages, is justification enough for the scattering of fragments.”[4]

Over the last several years, Prof. Peter Stoicheff of the University of Saskatchewan has been working to locate all existing Ege Portfolios, and to foster co-operation from their respective owners in creating an “Ege Medieval Manuscript Database” with the ultimate goal being the digital reconstruction of the complete books.[5]

Ege’s personal collection, including 50 unbroken manuscript books, was in 2015 acquired by the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library (part of Yale University Library.)[6]

I’d feel bad if Ege broke any complete and valuable books for these. But he is long dead, and the damage is done. I’ll save them and preserve them together. Should Professor Stoicheff want to digitize my leaves for his “virtual” restoration, I’ll cooperate.

But it is exciting to be able to “leaf” through the History of the Book and The History of the Bible leaf by leaf. Touching pages nearly a thousand years old. Touching pages from printed books that I could never own myself.

The Ege History of the Book portfolio contains 40 different leaves. The earliest is from a 12th century Koran. The last from a 1923 Bremer edition of the Iliad and Odyssey. Other notable leaves are from the Nuremberg Chronicle, Kelmscott’s Beowulf, Dr. Johnson’s Dictionary, and…

The Ege Bible contains 60 leaves. Imagine what a huge wondrous stack of collectible books that would be if they could be had intact. The earliest is from a 12th century French manuscript Bible. The last is from Bruce Roger’s 1935 Oxford Lectern Bible.

But wait! The colleague who offered this to me warned me one of the Bible leaves was missing. I asked of he could get a facsimile made of a leaf from the same Bible.

That brings us to: “Leaf insertion”

My colleague was able to get a photocopy from another Ege portfolio. He inserted it into my portfolio. So my Ege Bible Portfolio is complete and intact except that one leaf is an obvious facsimile.

Inserting facsimile leaves into defective copies of books is one way to “recreate” a complete book.

But an original leaf from a defective copy of a book can in also some cases be inserted in another copy of that same book which is missing that page. This can be a valuable match only if both books are identical editions. There have been scandals where, say, a first edition title page from an incomplete book is removed and inserted into a complete copy of a later printing—replacing that later printing’s title page. That results in an unhappy mismatch. That’s another good reason to work only with reputable booksellers.

Finally, leaf insertion—on steroids.

A colleague reminded me after this first came our about the lead insertion process called “grangerization.” This is named after the 19th century biographer James Granger. Someone can grangerize a book by inserting leaves of text or illustrations into a book in an effort to “enhance” the original work. The inserted pages in this case are related to the subject of the original work. So, say you want to enhance your copy of a book about George Washington. You could add images and text removed from different books. Some books were so grangerized they had to be rebound in multiple volumes because so much was added.

If you were to paperclip a book review into your own copy of a book, would that make you a grangerizer?

I dunno.

So if you find yourself in Maryland, stop by one of the three Wonder Book stores (or ALL three!) and browse our “leaf piles.”

Rest assured that no viable books have been damaged to provide these. Rather these leaves are “rescued” from books that most other booksellers would avoid or discard.

[…] And this blog? I’ll print it out and insert it in the current journal. In book jargon, that’s called “grangerization.” (See earlier blog) […]

[…] * A single sheet within a codex book is a leaf, and each side of a leaf is a page. A leaf book contains one or more pages removed from a defective copy of a rare or import book. — https://www.wonderbk.com/collections/breaking-and-leaves-of-gold/ […]