(This novel length story was written about 15 years ago. It was sent to a couple publishers, rejected and shelved. Here we offer the first few chapters—revised a bit. If you would like to read more, let us know!)

Introduction

This book began as the third volume recording my experiences in the used and collectable book business. The first two books were essentially anecdotes strung together concerning the events and people I have dealt with over the last quarter century. Most often their stories concerned my purchase of books from individuals. People tend to let go of their personal libraries for one of four reasons: death, departure, divorce, downsizing. The “Four D’s” as my now deceased mentor and erstwhile partner, Carl Sickles, was wont to say. I rarely acquire people’s personal collections for their want of money.

My interactions with these people and their books have often been poignant, sometimes tragic and occasionally humorous.

The acquisition of the collection that caused me to pick up my pen and begin this memoir was interesting enough to record, as had been dozens of others, but it did not seem extraordinary. However, as I delved into these particular boxes of books, things soon got out of control.

The events I recorded in the first two books were true—or mostly true.

I’m not sure about this one. Though somehow I experienced all of the following, I am unsure as to whether all of what transpired was real or true.

The books are real. That I know. I still own them. Many of them are set aside still unread. Those that are in French will probably never be read by me. My comprehension of that language is painfully slow. Also, I’m not sure I want to risk being drawn in again. Those I’ve read, experienced and the small portion of them I recorded in the following pages were consuming, not only in time but spirit and emotion as well.

I’m not sure I can afford it. I’m not sure I could bear to go through it again.

Chapter 1

“If you don’t pick them up, we’re just going to dump them,” the voice at the other end of the telephone growled at me.

Books must never be thrown away, at least not until I’ve seen them.

“We need the space. If you come get ’em, you can have ’em.”

When the term “free” is used my attention becomes intently focused.

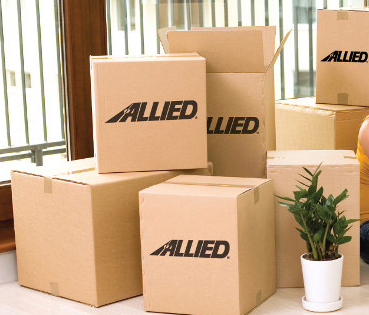

So the next day, Clint took the van and the “strong back du jour,” and three hours later there were sixty-seven Allied Moving Van and Storage boxes stacked on two pallets on a loading dock at our warehouse.

Clint was always big on small talk, which for him often turned into long talks. He had found out what facts the moving company knew. He relayed that story to me as the van was being unloaded.

The woman had gotten ill. The movers had been called to pack up her books and papers and have them stored while she moved in with her friend to recover. It was a lengthy illness, and she didn’t recover. The friend couldn’t handle sixty-seven big boxes in the apartment. The movers were stuck with them. The deceased pay no rent or storage fees. They had that motive to call us. Clint said they said they didn’t want to throw away all those books—that someone might be able to use them. The cynical side of me knew they would have lost time and money handling the stuff. They would have had to pay to dump the tonnage. I’ll give them the benefit of the doubt. Let’s say they needed the books to be gone, but they also wanted them to have a good home; a chance at further existence. Whatever their true motive or motives, we would conveniently make their burden disappear.

“They said she was a writer,” Clint confided in a gossipy tone. He continued telling her story, which I had paid a substantial hourly rate for him to learn, until I cut him off, and we both got back to work.

For some reason, this “free” collection was more intriguing than the dozens of evaluated and paid groups that were waiting to be gone through; sorted. So I dove right into this dead women’s collection.

No object is really “free.” Everything must be handled, displayed or stored. Every object must be moved or dusted. Whether it has inherent or sentimental value, or if it is simply “stuff,” every object is a burden. Whether you enjoy it or value it, everything you own robs your life of time and space. These “free” books had cost me two employees—three hours of payroll each. The van use had expended gas and wear on the vehicle. Now they were taking up warehouse floor space for which I was paying a per square foot rate.

Cynicism. It helps lower expectations.

I cut open the first of the neatly taped boxes.

Looking inside: “You get what you pay for,” I thought to myself.

It contained mostly home-recorded VHS videotapes. Each was labeled in a neat hand. “1983 French Open,” “1985 U.S. Open,” “1985 U.S. Open—Part III,” and so on. She had recorded hours and hours of professional tennis. To what end? The 1980s were a decade of fascination with home videotape. Movies, TV shows, birthdays, kids’ soccer games. Millions of people recorded way too many hours of stuff for future viewing. People would end up with hundreds of hours of tape on their shelves, only to discover they had neither the time nor the desire to watch again what they had already seen. The box also contained some tennis magazines, some newspaper sports pages with tennis headlines—it was all trash.

The next box was better. Mostly paperbacks but good titles. There was relatively hard-to-get literature in translation like Borges, Kundera, Mahfouz. There were a number of translated Egyptian and Arab novels and poetry in softcover by authors I’ve never seen before. Many were printed by Middle Eastern publishers I’ve never heard of before. There were a few hardback first editions of these once-collectible hyper-modern authors whose value had been killed by the internet. You can exclude Borges from that list. He is a favorite of mine, and his value has held up well. There were also some well-worn Italian glamour magazines—in Italian. Corners of some pages were turned down. Was she marking a “look” she had thought of incorporating for herself? Hair, dress, makeup?

Another box yielded binders and wire spiral bound notebooks. Mostly notes for classes she was taking. But upon closer inspection, some were for classes she was teaching. One notebook contained a translation of a Simenon detective novel from the French in her hand.

As I opened more boxes, I found myself becoming more intrigued by the person than the books. I started coming to work very early just to spend time unpacking and spreading her story upon the sorting tables.

The boxes were mostly mixed. A box seldom contained more than half books. She had studied ballet. There were books on how to dance. Books on the history of dance. Notes she had taken on dance. Books on choreography. Books I’d never seen before on Labanotation, a kind of ballet or dance annotation. And notebooks of unused and unusual graph paper. It was apparently used to compose ballet movements. I had never seen this before. Was she composing a ballet?

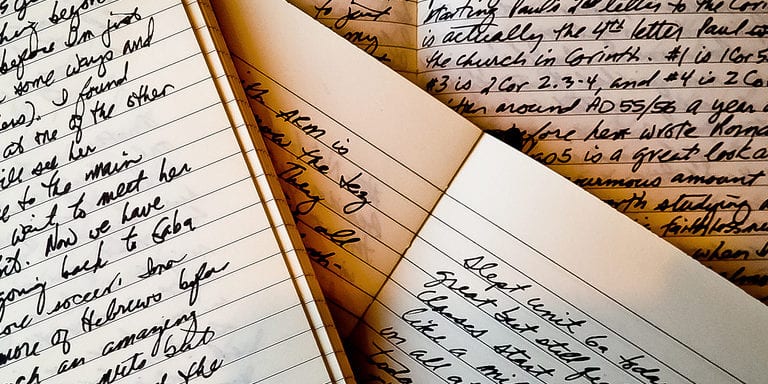

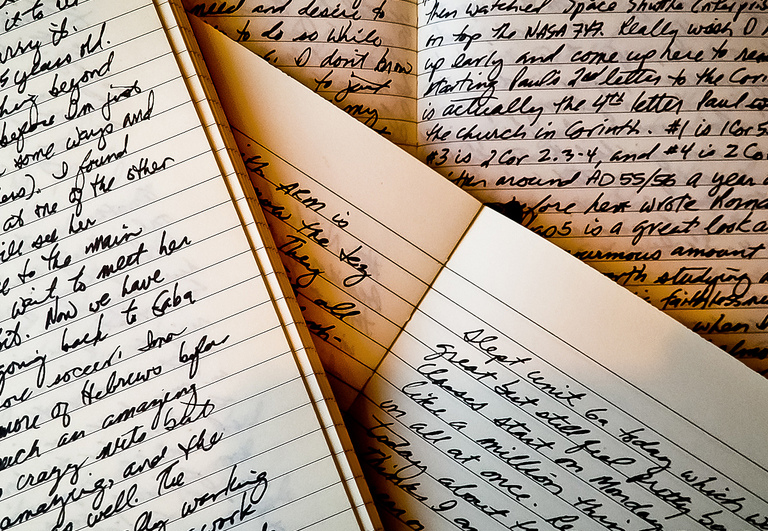

There were handwritten journals in many boxes. These journals contained poetry, diaries, prose, essays, notes, reminders. I leafed through them haphazardly. For some reason I couldn’t bring myself to throw away her creative writing. But neither could I sell them. I wasn’t interested in reading them. So I just began tossing personal things into a box to store them. When that box was filled, I started a second box. If a journal was blank or just seemed to be notes she’d taken, I saw no reason to save it with her creative writings. But I would flip through each of them pretty carefully just in case it might contain any of her creative work. She had started several novels, apparently. The journals had many different kinds of bindings. Some were just plain vinyl. Some were bound in decorative cloth. There were different sizes, different thicknesses. Many varieties. As if maybe she was thinking perhaps a style of journal would inspire her. Some were lined. Some were on fine linen paper. Some were in cheap composition books. I would flip through everything just in case. I pulled a black leatherette eight-and-a-half by eleven hardbound journal out and flipped it open to the first page.

(Dear Reader, I will quote her journal and diary entries for your convenience.)

“The times I have taken a man…”

I closed it quickly and tossed it in with the others and forced my mind to continue plowing through more of her boxes.

She had taught advanced French. Her course outlines were handwritten in spiral bound notebooks.

As more journals appeared, I ascertained they began spanning several decades. Some she had dated in her hand. Others I could estimate their vintage by their bindings. I’ve been handling books long enough now that I can usually tell the age of one within a few years by its binding, the style of its cover and/or the paper.

One morning, I opened a journal from the 1990s, probably the mid 1990s.

“When I was seventeen, I loved a boy…”

I couldn’t hold myself back this time. I sat down upon one of her unopened boxes and began to read:

We were a group of friends. Eleven of us. Six girls, five boys. We were the readers and writers in our dismal school. But Michael and I grew closer as our junior year progressed. He would show me his poems. The tension was there, but he would never take my hand or put his arm around me. Weeks and months passed and summer came. Various members of our group would go to a movie or congregate at one another’s homes. When it was just the girls, we would talk about “the boys.” There were other boys too. But I never said that there was one I wanted in particular. I would only tell my diary, my Vest, about him. But nothing happened. He would not cross that threshold that boys are supposed to. Especially in those long ago days. So I would fantasize in my diary. Writing silly girl words like, ‘Dear Vestibule, today Michael’s eyes met mine and held them.’ I was sure he liked me more than the others. But we were a pack. There was no indication that any of us would pair off. He told me he had shown no one else his writings. That buoyed my hopes and confidence substantially. I wished that he would write about me one time and show it to me so I would know how he felt. I loved his words.

Silly stuff.

But it was wonderful to feel so much. That is what age seems to have robbed from me. That fire that burned so brightly only occasionally ignites now. I smolder constantly hoping for one more love that will save my life.

That summer a plan began to develop, and Vest and I began to plot. It was a huge risk, and I have no idea how I would have made it work had I not had the dialog with my diary. For my diary was a sounding board. I could write out the what ifs. I could use logic and forethought to curb my emotions. I must do this right. For if he said no, I do not know what I would have done.

I wonder where the diary is now. My “Vest.” Maybe it is in mom’s attic. That is probably where the yearbooks are, too. All the old school stuff. Ancient history.

I remember his birthday was coming in a few weeks. I had no money or job, but I desperately wanted to give him something no one else could. I bounced ideas around in my diary. I could make him something. Sew him something. Knit him something. Draw him something. Write him something. But I felt I was so inadequate at those things. I could cook him something. No, that would be too transitory.

I wanted this gift to be something lasting. Something memorable.

I remember when my brilliant idea struck me. There was a grass-covered earthen dam where the eleven of us, or parts thereof, would often go. We would read plays there. Acting them out. Or we would recite poems aloud. Or we would bring food and picnic. Chris and Eric were learning guitar, and their attempts at folk songs would not torture us in such an open space. I remember Sylvia lost an heirloom ring there once, and we all scoured the grass for hours with no luck. We looked again and again on subsequent days. Her parents were furious. Sylvia was so beautiful, and I always felt plain in her blonde Scandinavian presence. But Michael wanted me I was sure, or he would want me. We would sometimes gather to watch sunsets on the dam. Our backs to Lake Westring and talk of truth and beauty and blue jeans and music.

It was there one evening that I got the idea; at sunset. Later, I wrote in my Vest. I would give Michael the sunrise. None of us had seen the sunrise at the dam.

Silliness!

Oh, but it was so serious and real then. I wrote him a note inviting him. A birthday card, designed and drawn in my best hand.

But Vest and I had not planned entirely. I remember waking with a start in the middle of the night a few days before. How would I get there? What could I tell my parents? How could I get the car before dawn? What excuse could I possibly have? I laugh as I write this now, but in some ways I feel the need right now to cry as well.

Somehow it worked. I cannot remember much then. The sun rose over the lake. No doubt the summer weather was fair. Somehow we offered and accepted a kiss. It simply happened. Then the sun was up, and we both had parents to return to. It was his first kiss he told me later in a phone call. He had called me near noon and asked:

“Did this morning really happen?”

That is how it should be. But I suppose it can only happen once. Truth. Beauty. That is all there is. He was beautiful and made me feel like my own blue heron…

The entry door to the warehouse has a chime to it. It sounded. I shuddered vigorously. Someone had arrived for the morning shift. I rose from where I was sitting. I rose from what I knew could become an obsession to begin my day’s work. I closed the ghostly diary and placed it in the box. I prepared for the work routine of problems, manual and mental labor, and the maximization of resources. But throughout that day, the dead woman’s life would appear to me, and my concentration would be broken. A couple of employees noticed it and asked me during the day if I was okay.

I wasn’t. I had held death, life, love, youth and age in my hands that morning, and I was anxious to discover more.

There was honesty in the dead woman’s words. Honesty is so fluid among the living. Hers was concrete. Permanent. She had nothing to hide. She had nothing to gain by deceiving me.

The next morning I arrived very early. I didn’t pick up where I’d left off. I don’t know why. Exploration? I opened more boxes. I was doing my job. But I was also immersing myself deeper in her life. Chronology leapt forward and backward from box to box. I found a photo of her as a child with a younger sister and brother on a couch. Then a photo of the same group twenty-five years later in 1970s attire.

The earlier photo was in black and white. Dated 1962. Julia, for that was her name, as I had discovered on correspondence in other boxes, was about seven or eight in this photo. She was the oldest. Her fair hair was cut short. Straight bangs half way up her forehead. A broad smile showed two front teeth missing. Her brother was four or five. Her sister about two years old. They were seated with their mother on a square cushioned vinyl couch. I imagined that old couch was a bright color. The 1960s. Her mother appeared to be short with almost elfin features. A father was not present. Perhaps he was taking the photo. The family group was seated closely. Almost on top of one another. The scene exuded the happiness of the very young and the happiness of a mother of the very young. The later photo was mid 1970s vintage. Soft faded colors. The brother’s hair was very long. It was brown and cut almost in a Prince Valiant style. Julia had long golden hair. Wavy and parted down the middle. It was over two feet long in this picture. It was so thick that it didn’t fall straight down along her neck. Rather, it angled out at nearly forty-five degrees until it reached the ends of her shoulders. Her sister, now about twenty, had long light brown hair pulled back tight looking straight. Her mother’s features had changed little in two decades. Julia, her brother and sister were now adults. They were seated as if they were reluctant to be there. It was probably a holiday, Thanksgiving or Christmas. The kids seemed to be anxious to go somewhere. Maybe they had friends waiting elsewhere. They barely touched. Spread out on a cloth sofa they were four separate people now. The brother’s arms were wrapped about his knees as if leaning forward to rise.

Julia was beautiful. She was leaning back. Her facial features were proportional. Her body was undefined because of the heavy clothes she wore and her brother’s forward lean. But she appeared lithe and fit. Her mother looked tired but satisfied. They were together one more time.

I put the photos down. I went to the box and looked for the black leatherette diary. The one I had closed two days before. The one whose first entry I had turned to and read those first words of her intimate entry.

“The times I’ve taken a man…”

That was an insight. Is that how they think? They “take” us. It was more than intriguing. After a lifetime of mystery—of wondering what women really feel—here I was being told in black and white.

This dead woman could open my eyes to mysteries and grant me epiphanies. Perhaps.

Then I had second thoughts. I shouldn’t look at what appears to be a diary. I value my privacy. I stopped and put it back.

After several weeks, Julia’s life was whittled down to about forty unopened boxes. Thinking about them becomes a metaphor. My life has had many compartments. Some doors are better left unopened. But the boxes are here, and they need to be sorted. I can salvage the impersonal pieces of Julia’s life and find new homes for them. There are now, however, four and a half boxes of personal pieces which I have segregated. What will I do with those?

I’m now somehow attached to her. Duty? Responsibility? I am in possession of her life’s work. Or is it curiosity? I don’t know myself well enough to be certain of my motives. But no one else here at work will be going through these boxes. Her secrets are between me and her now. Because something makes me think I will find something important in these boxes. Certainly nothing rare or collectible. For there has been nothing to indicate she was ever anything but a scholar with little money. But perhaps there will be insights of great value to me and what’s left of my life. For although, from what I can ascertain so far, she achieved little by academic or financial standard, she did accomplish a great deal in many creative and scholarly fields. More importantly, thus far I’ve seen no indication she was dissatisfied or depressed which seems unusual for someone as introspective as she was.

A life of continuous and varied intellectual curiosity. A life of writing and thinking. A life of no whining or complaining that I’ve seen so far. Maybe I can learn the discipline.

There was over an hour before anyone else would be at work. As long as I opened no box of distractions I could probably sort one or two boxes in that time.

The first I opened contained calligraphy and lettering exercises in a style I’d never seen before. Some were finished works. There were about twenty sheets laid out on grids. Almost like crossword puzzles. A different letter in each block. Each letter was stylized differently. The letters spelled out words. The block between each word was filled with a miniature drawing. The drawings were stylized devices, mostly reflecting what could be architectural ornaments. The words formed verse. Brief poems, almost Haiku. They were lovely. She illuminated her own words. Was this her own invention? I read them until the door chime rang in the real day.

Chapter 2

One morning I found a small octavo brown leatherette volume. I flipped through it backwards to see if it was resaleable. It was blank until I got just to the front. Only about the first dozen pages were written upon.

It was an “Anything” book—a popular cheap line of blank books meant for words or drawings. There was lots of gold embossing on the front cover and spine to give it a valuable look. But written in pencil in the upper right-hand corner of the front free end paper is “198.” No dollar sign. And a letter code “O” beneath it. It was a bargain book in the days before barcodes. This dealer wasn’t even using pricing stickers. Come to think of it, neither was I about that time. The “O” was some book dealer’s code either signifying a wholesale cost or date received or a supplier. Maybe it came from Outlet—a big bargain book wholesaler in that era.

The endpapers were cream-colored paper, and Julia had entered her name, “August 1980” and “Essays” on the front free endpaper in blue ink.

The pages were white. Pretty high quality paper. Unlined and unpaginated. The essay on the first page was titled “On Friendship” in a very neat hand. There were no corrections. This makes me think she drafted elsewhere and copied it here.

Each of the first twelve pages had a different one-sheet essay. The verso of each page was blank.

“On Friendship.” “On Hope.” “On Waiting.” “On Focusing.” “On Tea.” “On Music.” “On Translation.” “On Men.” “On Willowy Curtains.” “On Summer Storms.” “On Being Alone.” “On Losing My Temper.” And finally, “On Sneezing.”

Then eighty or ninety blank sheets. I guessed she would have been in her mid twenties when she wrote these.

I thought back to my life in August 1980. I was in my early twenties. That month I remember vividly, for that it was the month before I opened my first store. In feverish preparation, I was working harder than I had ever before in my life. I would drive 150 miles daily to and from a farm in West Virginia filling my Ford F150 pickup truck with as many books as I could. I was guessing which books I could sell selected from hundreds of thousands—or millions—in the West Virginia farm hoard. For I knew next to nothing about buying and selling books. I knew even less about business. I was also learning how to build bookshelves as I went along. I was designing the layout of my store organically. I’d made no floor plan.

At the same time, not too far away geographically, Julia was being introspective. These were exercises for her, not only in personal philosophy, but in finished writing I was sure.

Therefore I felt no hesitation in reading these. These were meant to be read.

The first, “On Friendship,” was a little trite. She had clearly had a spat with someone and was writing a defense for this instance of conflict. But she expanded into her philosophy what friendship is and how to save strained friendships.

“On Hope” must have been written on a very hot day. She spoke of white linen trousers and the sun melting tar. And she has experienced a “blind urge—is that the animal in me or the saint—that, despite everything, still moves me from hope to hope.” She had detailed depression and depressing things. Yet she finished moving from hope to hope.

The next, “On Men,” was the only essay in this book with cross-outs and corrections. She changed “they” to “she” and “are” to “is.”

Now what do you think you’re gaining by peeking at this woman’s thoughts?

Any hope of an epiphany was dashed by the arrival of herself. My book muse.

I suppose I should explain, lest you think I’m crazy. I am a bookseller. Used, collectible and rare. I have been for over two decades. In the twenty-plus years of my overnight success story, critics and competitors have often wondered and queried:

“Where does he find those books? Why does he seem to flourish in a business which is notorious for the poverty of its professionals?”

For years I wondered the same things.

Then about six years ago, during a flurry of book ventures between myself and Irish booksellers and collectors, she made her presence known.

Part guardian angel, part chide, part book scout and, most of all, sarcastic—my book muse has apparently always been there. Silent until the revelation that it was she (according to her) who was responsible not for actually guiding the successes I have achieved, but rather making sure I am somehow made aware of unusual or golden opportunities I might otherwise overlook. She puts me in their way (or vice versa) where, if I’m not too dimwitted, I cannot miss them.

In my trade, at the level I deal in, there are dozens of doors I could open each week. Most would be mundane or fruitless. Most phone calls for house calls I am not able to return. The memo sheets get crumbled and tossed in the trash. Why some of the least intriguing leads have been pursued to dramatic or poignant conclusions has always been difficult to explain.

She is Irish, I think. Or was. Or always has been. For I am not sure what she is beyond invisible.

Ghost? Faerie? Conscience? Sometime corporeal being? Her voice I hear in my mind is sweet and lilting. Her brogue would always be melting were not her frequent verbal jabs so stiletto sharp.

Since that first revelation, she appears (or doesn’t actually appear) when it seems to please her. She will drop hints about actions I should take. Or she will gloat a bit, letting her role in a memorable event be known after the fact. Often it seems she arrives solely to give me grief. But once she’s left some nugget of information will arise from our dialog which will prove valuable information—sometimes financially—sometimes in other ways.

What she does or where she is when she is not here I don’t know for she’s never answered questions or offered information about herself. Maybe she hangs out in Tír na nÓg with her compatriots.

If she is not real—if she is just a figment of my imagination—a bit of madness, at least it is a gentle madness—a harmless companion who sometimes appears during the hundreds of solitary hours I spend among other people’s books.

Some doors are better left unopened. And besides, look about you. You have thousands of boxes about. There is your real work, she continued.

I was angered. Not only by her interruption, but at her opinion as to what I should be doing with my time.

‘Business!’ I thought back at her. ‘I work hard and you know it. I can learn something here and maybe make some sense out of my life. Julia has me writing again.’

Ahh, that would be your reams are fictional memoirs. You think Julia’s boxes might add twenty pages to your dusty piles.

‘I was thinking more. Much more.’

You’ll not find much value in this book collection. And distracting yourself with this woman’s life and loves will not boost profits.

‘Mankind should be my business sometimes,’ I countered. Knowing that even though it was over the top, the paraphrased English quote by Dickens would raise a bit of the ire in her.

Mankind? Or womankind? I wonder at all your motives here. She was beautiful to be sure.

‘Jealously,’ I thought?

Pish!… Don’t be ridiculous.

But the reply came a little too quickly and urgently.

‘Is it? Or are you having a problem with my becoming philosophically attached to another woman?’

I warn you, I can drop you like a hot potato.

There was still something tentative in her tone.

‘I want to write a book. One book. I’ve put off really trying so long. I need inspiration. If it’s possibly in these boxes, I’m going to go for it. I need inspiration.’

There was a few moments’ pause between us.

‘I need this,’ I continued. ‘You could help.’

I’m not that sort of muse. I know books, but not the creation of them.

‘You know me. Maybe you can branch out.’

I’ve no time or patience to be holding your pen.

‘It’s not that. A little encouragement sometimes. And maybe some of your challenging criticisms occasionally to keep me on track. I need to put some words to paper. You know books and authors and writing. And besides, you’re Irish, aren’t you? Creating literature is in your blood. Maybe, for just a while, you could be two muses at once. Just as maybe I can be a bookseller and book writer at the same time.’

Perhaps… She thought back to me in a far more sensitive tone than I thought her capable of. Perhaps. Then, she was too quickly gone.

Blood? Did I really mention her blood?! Does she have blood? I hope I hadn’t said something offensive.

Chapter 3

Of course, with these grand intentions to begin a book about Julia, problems immediately arose at work, as they so often do, and suddenly I had no time to read her works or begin writing about them.

The next day and the next were consumed by issues of such magnitude that they took precedence over my desire to create. When I was done working for the day, there was no energy left to pick up pen and paper.

Yet, like the thought of new and fervently beloved’s face which appears whenever the mind’s eye has any respite, I yearned for the red pen and yellow legal pad and time for creation. But I was denied again and again by circumstances beyond my control.

An unavoidable business trip to Manhattan was approaching, and I had to redouble my daily work so I would feel comfortable about my absence. “Getaway” days are especially intense. I don’t know why my productivity skyrockets on these days. Maybe it’s the deadline—working as though there was a gun to my head. Suddenly it was time to go. I had to get on the road now or miss the best deals. I grabbed a box of Julia’s writings. It was no more than half full. Notebooks and folders I had culled were tossed in it haphazardly, left just as they were when I had separated them from the trash and the saleable weeks before. I put it on the passenger seat and soon I was flying up the highway toward the city which is the center of the known universe. I was headed for the Book Expo. Hundreds of publishers, vendors and book accessory sellers were arranged in twenty-five hundred booths. It would take a full day to stroll up and down each aisle on the two levels of the Javits Center. But I was going there only to buy books, so I focused on the booths of remainder dealers. The Internet was gobbling over forty thousand books a month, and I needed to get fodder to feed it. I looked for familiar faces at remainder house booths and asked:

“Anything for me?”

Then the wheeling and dealing started. Both parties knew their businesses. Boxes of dust jackets were set before me. Marked down selling prices were written on the backs or on stickers affixed to front of the sample dust wrappers…

“Yes.”

“No.”

“Five copies.”

“Fifty copies.”

“Two hundred copies.”

“I’ll pass on that one.”

“What if I took them all?”

The marked price was just a starting point. It was my job to find how low my counterpart can go.

I usually bought across the board and during some of these sessions, there was give and take between us. If their “lowest” selling prices seemed to start trending upward, I began passing on titles. If I was offered a great deal, I’d buy deep and often more than I wanted as a way of thanks, and hoping to encourage them to similarly cut pricing on subsequent titles.

After the show closed, I attended a couple cocktail parties and a dinner. Finally, I got back to my room. I opened the curtain. It was striking. My room was fifty-two stories above Broadway. The pit of the demolished World Trade Center lay directly below my ten-foot windows. It was softly and respectfully illuminated for all to see. Beyond it, the Hudson River cut a dark swath between the twinkling lights of downtown and the New Jersey cities on the other side. I stepped behind the big couch which was set just about a foot away from the window. I leaned back against it and tried to pick out landmarks. The couch was facing inward towards a huge flat screen TV hung up on the wall. I preferred to look the other way, so I swung the couch around, sat down and put my feet up on the windowsill. I watched the world.

It was nearly midnight. I knew this because on the far shore was a large clock that must be at least twenty feet in diameter. It was lit and beneath it in deep red letters glowed the word “Colgate.” I had gotten out several of Julia’s notebooks, but had no energy to open them. I put them next to me on the couch and rested my left hand upon them. I gazed out at tens of thousands of lights. So many different configurations. Some were high, rising to the tops of office buildings. Others ran horizontally down at street level. Some twinkled white, like stars in the sky. Others were less pale, less white. Then there were dozens of different colors. Some were bold and brazen. They seemed to go on forever. I wondered if that was California just beyond the horizon.

I wondered at mankind’s energy, creativity and desire to put this all together. I wondered how it all works and holds itself together.

I thought of living here. On top of the world. Not always. But more frequently.

Some soft lights of tug boats pushing barges up or down river moved across my tableau. Then a fifty-foot tourist cruise ship passed with its two decks brightly lit.

When I looked again, the clock’s hands were approaching 3:00 a.m. Over a hundred and eighty minutes had passed somehow. I had fallen asleep, I guess. I had been dreaming. I had dreamed my head had been upon a woman’s shoulder and my arm and shoulder pressed against her side. I had felt a warmth and contentment so long absent. I had tried to repress true consciousness, fearing she would disappear and empty night return. I dreamed I had dared to turn my eyes upward and had seen a beautiful profile softly illuminated by the thousands of lights outside.

Then the vision returned in real time. She was here now.

Was it Julia? She was staring straight ahead, unmoving. She did not mark my presence. I hoped to hold this intimacy in view. If I closed my eyes, she might not be there when they opened.

It was her. The golden curls reflected the city’s lights. She was as she appears in the only adult photo I had of her.

I opened my eyes, and the clock read 4:10 a.m. My head was on the armrest and the rest of my upper body was propped up upon tossed pillows. My eyes scanned back to this side of the Hudson and back into the room. Upon the broad window shelf before me laid a yellow legal pad and a red pen.

Exhaustion dissipated, and I began to write by the lights of the city.

There are no comments to display.