The road is long

— The Hollies

With many a winding turn

That leads us to who knows where

Who knows where

But I’m strong

Strong enough to carry him

He ain’t heavy, he’s my brother

So on we go

His welfare is of my concern

No burden is he to bear

We’ll get there

For I know

He would not encumber me

He ain’t heavy, he’s my brother

I never thought I’d own these books again. I’d selected many of them carefully over the years. Some were gifts chosen to inspire him or supplement a current subject which he had indicated was of interest to him. Some were simply his—left at home with Mom and Dad and stored with me for a couple decades after they died. I’d returned them to him as they resurfaced. But most were strangers. Books he’d gotten for himself in his own life—outside of family.

I’d been in dozens of houses like this to pick up books, but this was the first time I’d been in one where the pictures attached with magnets to the refrigerator included images of me.

“Hi, Chuck.”

I’d known that voice my whole life. Tony is my second oldest brother.

”Hey, Tone. What’s up?”

He was never one to call without a reason.

“It’s Jim. He’s pretty sick.”

Jimmie was the brother nearest in age to me. But still a full decade older.

“He’s pretty sick…” That could mean many things. I said nothing.

“He’s got cancer.” That could mean many things. I said nothing.

“He had a biopsy last week. I flew in yesterday to go to his doctor with him and hear the results.”

Time compresses for me at times like this. As Tony spoke, my mind was reliving childhood scenes with my big brothers which had occurred more than two score years earlier. The two planes were co-existing. Both seemed equally real and unreal.

“The doctor said six to twelve months without treatment.”

Clearly implying, my mind leapt to the conclusion, that with treatment there would be more months. A horrible situation. But we had a cushion. Though the four brothers didn’t speak often and seldom visited, instantly the old family was one again.

My work and family were in the throes of a dreadful summer. It had been excruciatingly hot almost every day. Day after day in the high nineties or over a hundred and bone dry. Creeks stopped flowing and reservoirs became muddy puddles. Strong mandatory water restrictions had been in place for weeks. The gardens and lawns had surrendered far earlier than usual and there was no water to revive them. War rumors abounded overseas. The stock markets were plunging. A freak blow from my son’s soccer ball had ripped the bicep tendon from the bone on my left arm. It was to be surgically reattached, rendering me a one-armed bookseller for a long period of recuperation and rehabilitation. I am left-handed. So no writing for a while either. I was to be in an immobilizing cast for six weeks. Seemed like tough time to me…

And now, one of my three brothers had been handed a death sentence.

“With treatment,” I thought aloud.

Light at the end of the tunnel. Surely, it would rain again. Fall would come and cool things off. My arm would eventually heal and Jimmie’s disease could be cured.

Time heals things. It always heals things. We had time. Six to twelve months. Jimmie would go to specialists. Awful things would need to be done. I could see the script. I began calling him frequently. Asking if he’d seen a specialist yet.

“No. They’re working on it, but it’s August and they’re on vacation.” Jim’s voice was genteel. His manner cordial. An artist. A musician. A writer. A bachelor. Laid back would be an apt description. He was fond of saying he was “older than rock n’ roll.”

Finally, after three weeks and after Labor Day, he got his consultation. Coincidentally, he had become suddenly weak and a friend went with him for moral as well as physical support. It was she who called me.

“The liver specialist said there was nothing to be done. He called it a lethal tumor. He told Jim two months.” Her voice caught. I could feel the tears at the other end and I could feel tears at my end. “Afterward, he took me aside and said it would probably be more like one month.”

Those words had a physical impact upon me. The human reactions, all too common and melodramatic, struck me. Stone silence coincided with my reflection on the 2 score years of my conscious knowledge of my brother. Ancient times when he mentored and entertained a tiny me. His early glory days in rock and roll music. His long plateau as a hotel worker and bar sitter when the creative juices dried up. And for the last years, his intense study of theology.

“What should I do?” The question was reflective, rhetorical, but also an appeal to the stranger on the other end of the line.

“I don’t know. Would you like to speak with Jim?”

“Chucky!” It was his usual salutation. The inflection was as it always had been. But the voice was far away and fragile. It was a little sleepy, too. We spoke of many things but never touched on his death sentence.

“I’d like to come visit you soon,” I said, finishing up.

“Sure… I’d like that…” His words were stretching out further with each sentence. It was either fatigue or else his mind was drifting to other matters.

“He should come home with me I’m selfish. I want him with me,” said my oldest brother — Joe.

There had been a flurry of phone calls between the three ostensibly healthy brothers. The main thrust of the conversations, which were frequently punctuated by tears, was what should we do about our rapidly declining brother? He was a bachelor set in his ways and routines in a city five hundred miles from the closest of us. We wouldn’t drag him unwilling from there. None of us knew if his structure of Nashville friends could see him through this. We would debate our brother’s fate. Yet none of us pretended to know what was best. At some point in almost every conversation the finality of it all would cause one of us to seize up.

“I’ll have to call you back in a while,” one of us would choke out.

Finally, Jim seemed convinced that he should come live with Joe and his wife, Freddie.

“But I’m not ready yet. There are still things I want to do here.”

The doctor said this particular disease would weaken him and he would sleep more and more. He would sooner or later need Hospice care. There’s not much “later” in a thirty-day term.

“I’m going down there,” I said. “I want to see the situation. If he can be convinced to come back, I’ll bring him back. His cat and as much as of his stuff as he wants to Joe’s. We’ll fit as much as we can in my truck.”

My truck was a Suburban. Over the years I had a number of them. It was a great vehicle for hauling books and people. Two of the three rows of seats could be eliminated for a full load of cargo. Books of course. With all the seats in place, it could comfortably seat eight people. I loved my years of coaching soccer.

Joe, who lived sixty miles away, wanted to accompany me. We would drive the eleven hours together. Tony would fly in from the West coast again.

None of us knew what we would find.

The morning we were going to leave, Joe arrived two hours late. I had wanted an early start.

“Problems at home,” he said, then invoked the name of his son and daughter.

My nephew and niece. Perennial problem children. Joe was sixteen years older than me. A former Marine officer and pilot. A Naval Academy graduate. After a couple helicopters had been shot out from under him in Viet Nam he‘d given up his military career. He had a long tough road after he had last slammed into the jungle. Pieces of metal became permanent pieces of his body. He was a different brother after he’d returned from the other side of the world. The jobs he had selling steel and iron things to wholesalers paid the mortgage. But I knew he had aimed higher. Much higher.

He was more an uncle than a brother really. He had left home when I was still a baby. This would be our first adult journey of any consequence together.

“Got your bag?” I asked. Trying to move things along.

“Yep.”

He pulled a pillow and a blanket out of his old Cadillac.

“Need a hand?”

“Nope.”

He lifted a small cooler out of his trunk.

“I thought Marines always traveled light.” He handed me a full bag of groceries.

“I like to be prepared.”

“I thought that was the Boy Scouts.”

“Nope. We’re Semper Fidelis. Different motto entirely. Hold this.”

He handed me a massive black metal flashlight.

“Put it under the driver’s seat.”

“You think we’re gonna be hijacked?”

“Ha, ha.” His piercing blue, pilot eyes locked onto mine. No more nonsense from the civilian little brother.

He handed me a briefcase. “Turn the truck on.”

“Uh. Okay.”

He put the driver’s side rear window down a few inches and stuck a big plastic American flag bracket on it and raised the window up.

He handed me an empty cat carrier. “For Jim’s cat,” he explained.

A spacious storage area was filling up fast. Finally, he pulled a fairly large suitcase from his back seat.

“Are you ready?” he asked impatiently.

We drove out, the plastic flag flapping annoyingly behind my left ear. About ten minutes into the trip he unwrapped his cigar.

“Mind if I smoke?” The cigar was in his mouth and the match struck when he asked that question. The stogie lit, he shook the match out and pulled the ashtray open.

“Goddamn it!” he said. As he’d so often said the last thirty years when he was the least bit frustrated. If it wasn’t Goddammit it was Sonofabitch. It was full of pocket change. I’d never used it for cigarettes. I unlatched it and dumped the change into the coffee holder.

“I’ve never used it for ashes.”

It was an interesting trip. Bonding with the brother that had always been so distant. This would be the most time we’d ever spent alone together.

We exhausted the family reminiscences before too long. We finally began talking about Jim.

“Well, he’s coming back with us.”

Joe, the Naval Academy Grad, Marine helicopter pilot who’d been shot down twice flying twin rotor Sea Knights was exerting his Officer in Charge persona. Like Nam we would swoop in Deus ex Machina and extract the wounded to safety.

“What if he doesn’t want to?” I replied.

The conversations among the four brothers had not reached a consensus on this point. I was prepared for anything. Jim seemed certain that he was not ready to leave the home he’d occupied for fifteen years. Joe was equally adamant that Jim and his cat “Dude” (Deuteronomy) would be loaded in the Suburban and come back to finish living with him. Tony was leaning for keeping Jim with friends in Nashville.

He reminded me Joe and Freddie’s home in York would frequently go dysfunctional. I was undecided.

I hate, dread and avoid finality.

I thought this would be an exploratory trip. We would see Jim’s physical condition, his living conditions, and try to gauge how much support he could count on from his friends. I sensed there would be dilemmas for three of the four of us who were uncommitted.

When we arrived at his old bungalow in Nashville I gathered my emotions. I’d broken up a few times during the phone conversations and, not knowing what I’d find inside, I had to steel myself. I promised myself I would not betray my emotions.

We knocked and let ourselves in the front door. Jimmie was eight feet off to the right on a sofa. He looked like…something out of World War Two photos…a concentration camp victim. His face was skeletal and jaundiced. He looked like he weighed half as much as when I’d last seen him. His hair was unkempt and a dull gray.

Jim had always been dapper. He’d worn white silk scarves. He once had a pair of bright yellow boots.

“Like Tom Bombadil,” he had said back then.

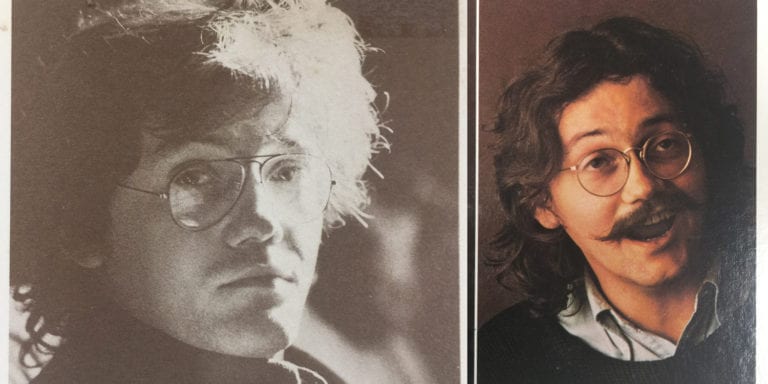

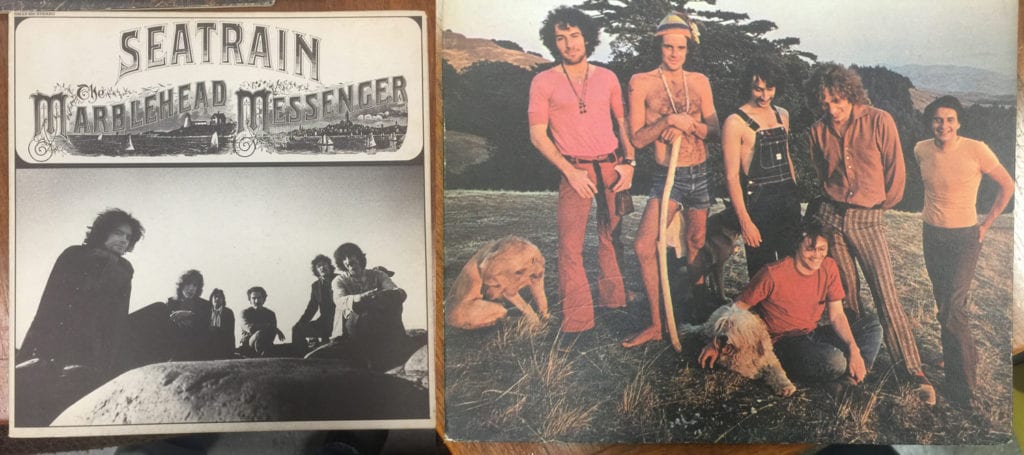

The photos on his record albums showed a handsome beautiful young man frozen in time.

(Strangely vinyl records have had a huge renaissance in recent years. And every once in a while my mind will be struck when I come across a Seatrain album while I’m sorting the mountains of LPs that come in.)

He was much worse than I imagined.

“Chucky! … Joe … Hey! … You made it,” his voice was thick and slow. He strained to be light and upbeat.

I stepped to the sofa and leaned over and embraced the frail body.

The bones of his shoulders and upper back stuck out like wooden trim on a Victorian house.

He was wearing a red and black checked bathrobe with a white T-shirt beneath.

The room was in disarray but not beyond what could be considered normal for a bachelor. His white long-haired cat was curled up next to him.

Tony appeared from the kitchen. All four of us were in the same room. A convention of all four brothers had seldom occurred in the last few decades since one by one they had moved on leaving me, the baby, to care for our aging parents. We’d gotten together after Dad died when I was 20. And after Mom died a year and a half (of suffering horribly) later.

The tiny room began to feel oppressive to me. Too much sadness and a prospect of extremely difficult decisions. I distracted myself by inspecting Jimmie’s books. I could always get lost in someone else’s book collection. I’m a terrible guest. I often go right to their bookcases after being introduced. There were a lot of familiar spines. I’d loaded him up pretty well over the years. Many times he would express a special interest in something, and I would ship some related titles off to him. There were plenty of his own books there too. A narrow five-shelf bamboo case was filled with Bible studies and Christian titles. For the last six years he’d taken a progressive course of advanced Bible study. He was no foxhole convert. Small medals of scholarly achievement were pinned to a bit of leather which hung on the wall above this bookcase.

“How was your drive?” Tony was at my shoulder looking at book spines next to me.

“It was fine,” I lied with an abrupt tone. “I’ll tell you another time. Did you know Jim looked this bad?” I added sotto voce.

“He had a bad weekend. When I was here two weeks ago he was still driving and eating.”

“How does he feel about leaving?”

“He keeps saying he’s not ready yet. He still has friends he wants to say goodbye to.”

“He doesn’t look like he could travel now.”

“Chucky…?” The short syllables were drawn out by the dying man’s hoarse voice behind me.

“Yeah, Jim.”

Joe says you found some Frostie root beer on the way.”

“Yeah. I haven’t had any for years and years.”

“That was always the best one.”

I agreed. As a child, I made a study of root beers. Hires, A&W, Dad’s were all fine. But Frostie, with a little Arctic elf painted on the bottle and icicles sculpted in relief just below the neck, was the best of all.

I’d spotted some in bottles at a stop on the way south. I hadn’t seen a bottle of Frostie since I was growing up outside of Buffalo.

Tasting a Frostie after all these years gave me a Proustian moment. When I was a small child all bottles were returnable. I would scavenge the neighborhood for those discarded as litter. Small bottles were worth two cents. Quart bottles a nickel. I’d pull my wagon along the roadside peering in gutters and under shrubbery for hidden treasure. When I found my quota I’d pull up to the side porch of the little slat wood neighborhood store Boekel’s and line the bottles up on it. Green, clear and brown glass. Thick and heavy. Some showed wear and scratches from repeated use. Nehi, Coca Cola, Royal Crown, Crush, Vernor’s, Pepsi. I would go around and enter the front door and tell Mr. Boekel of my booty. He’d go through a side door to make an accounting. While he was gone I’d shop. I knew to the penny the figure he would arrive at. I would place candy bars, a soda, maybe some potato chips on the crowded wooden sales counter. I would exhaust my funds to the last penny. Large pretzels sticks pulled from a tall round glass humidor with the printed tin top were two cents each: Double Bubble or Bazooka bubble gum were one cent each. Fire balls also cost a penny.

Mr. Boekel would return to find my purchases laid before him. He’d go through the ritual of counting the coins into my hand. He would sometimes grumpily comment on the mud or ants that had been attached to the assets I’d traded him. He would total up my purchase and I would count the exact same coins back to his hand.

A lifetime of pennies and nickels and dimes. My mom would often send me over there to get her cigarettes. She smoked Larks. Happy sounding things—Larks—song birds and fresh air… She’d give me a quarter for the pack of 20 and an extra nickel so I could get a Milky Way or something.

Touching a Frostie root beer bottle brought that childhood ritual back to me.

I opened a bottle and handed it to him. He took a sip and smiled.

We conversed for a bit on the shared ancient memory of Boekel’s store and brand name kids’ foods and drinks. Some were extinct, but many were extant.

The next few days were stressful. The four brothers debated Jim’s fate without actually mentioning the finality for every decision we would make. Jim seemed to grow weaker by the hour. But he kept repeating, “it’s not time,” almost as a mantra. He didn’t want to shed twenty-year roots in this southern city. It would signify an ending, I surmised. Moving on to a place from which he would not return.

We went to see his doctor. Not the specialist who called his tumor “lethal,” but the internist who had held out some hope initially and who had, I believe, dropped the ball by not getting Jim into the specialist’s office immediately so he could make the best use of any time left to him.

He was affable when we were ushered in. Six men in a small examining room. Jimmie seemed even more shrunken surrounded by five big men. Three brothers, the doctor and Jim’s best Nashville friend. I asked leading questions about his prognosis and the course the disease would take over the next weeks. I wanted Jim, and all the rest of us, to be fully informed about the momentous terminal decisions that soon must be made.

“Well, Jim,” the doctor spoke with a soft Tennessee drawl, “as horrible as it is, this breed of cancer is somewhat merciful. There’s not a great deal of pain and, I believe, you’ll be able to manage it with the prescriptions I’ve given you. Your liver will lose its ability to filter toxins from the blood. You’ll lose more and more energy. You’ll sleep more. Your cogitative processes may become affected. Eventually, you’ll need hospice care. Eventually, you’ll doze off and not wake up.”

…”Not wake up.”…

This must be like a bad dream to…my big…now little brother…Jimmie was shrunken and slumped.

I bet he’s hoping to wake and find his distant brothers distant and he and Deuteronomy curled up on the couch watching a good movie.

But we were here. And he must decide if he wants to stay and face the end game alone. He could trust his care to friends and strangers with only periodic visits by family. None of us could move here for an indefinite month or two.

“Would Jim be too ill to travel?” I asked, hoping the doctor would help make the decision for us.

“At some point hospice care will be necessary. At that point, travel will be out of the question.”

Time was becoming more finite in that cramped office. If he left Nashville, he probably would never come back to his home. If he did not leave early enough, he might not be able to leave when he wanted or needed to.

Jimmie and time were shrinking before my eyes.

After we left the doctor’s office, Jim asked us to drive him around his hometown and we obliged. He pointed sights and told us their stories but had no strength to leave the car to get out and visit them.

We returned to his bungalow joking and reminiscing. All of us avoided bringing up the decision.

The next morning in preparation for the inevitable—hospice delivered oxygen. They hooked things up and Jim began to suck on the mask. That afternoon he went into a deep sleep. Tony, Joe and I decided to go out to dinner. Nashville food is fantastic. Southern cooking and hospitality are wonderful. Over “meat and threes” we rehashed the pros and cons.

It was an impossible decision. Joe was getting angry and drunk. Tony was becoming defensive. Their childhood rivalry was reheating under the stress. Joe lit a cigar despite the no smoking signs surrounding us.

“Come on, Joe, put it out. You can smoke when we leave.”

“I’ll do what I do when I goddamn well please. Where I want to and when I want to.” It was his Marine mode.

It got uglier. Brothers fighting as only brothers can. Finally, I could no longer stand it.

“I’m leaving tomorrow. If Jimmie wants to come, fine. If not, I’ll come back whenever he’s ready.”

When we got back to Jim’s bungalow it was decided that I would stay the night in case he needed help. Tony and Joe went to the hotel. Jim was sleeping deeply. His chest would heave for deep breaths. The oxygen regulator, with its clear plastic tube looping around his neck and into his nostrils, breathed too, only at a different cadence.

I walked around his little bungalow. He’d been very satisfied there for nearly twenty years. He’d rub shoulders with the music industry. Old friends would recognize him and they’d chat in a bar.

There were his records. 10 or 12 had his songs on them. I pulled some familiar books off the shelves and looked inside. They were books he’d had in my childhood home in Buffalo. He’d had the 3rd floor garret to himself in the old stucco house on Washington Highway in Amherst. I’d sneak up there sometimes and poach books or records to put on my shelves on the second floor. The oldest boy got that space until he moved out to college.

We’d moved away from that great house before I could take possession of that special bedroom and semi-private floor.

He had a lot of modern lit. A lot of poetry. History…good stuff.

“There’s some familiar Joyce…” I thought.

Jim had been something of a Joyce scholar at UB—the University of Buffalo. He’d given a lecture as an 18 or 19 year old. A thin limited edition was written and printed. I haven’t seen that book since I was a kid. Lost in a move I suppose. Jim didn’t seem to have one either.

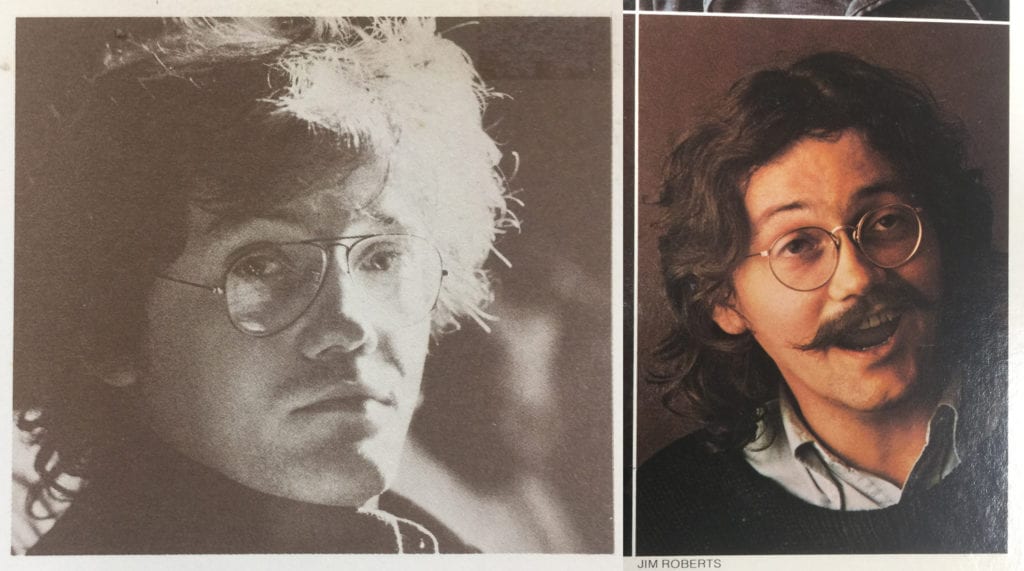

There’s his copies of Lord of the Rings! I flashed back to 1965. A ten year old sitting on his double bed whose metal springs sagged in the middle. Jim had stuck his head in the room.

“You might like these. They’re full of dragon spit and elven snot.”

He had tossed three beat up paperbacks onto my bed. The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, The Return of the King.

“Weird looking covers,” I remember thinking.

This is what they look like now:

Those books changed my life. I reread those Ballantine editions many times. Often by flashlight hiding under the covers late into the night. If Mom or Dad had caught me it would have been:

“Stop reading and go to sleep. Its a school night!”

Tolkien became the touchstone in my reading life, my book life and much of my personal philosophy.

Funny how a little block of paper can change the rest of your life.

He’d given me a lot of other books too over the years of my youth.

When I became a bookseller, I’d repaid the favor.

“Peter and I are working on a rock opera “The Dogs of Pompeii.”

There were a dozen or so books I’d sent him on Pompeii.

There were books on Nashville, Tennessee, the Natchez Trace…

They’d all come back to me now. Many of his books had been my books and now they would become my books once again.

It had been a surreal week. He was only in his midfifties. I’d visited him a year before. He’d been the dashing figure he’d always been. Earring in one ear. Thomas Jefferson ponytail. White silk scarf trailing behind him. Orvis blue blazer perfect for any time any place. He was always far ahead of the fashion trends.

He’d always had beautiful girlfriends.

I recalled my parents reluctantly letting me visit him for a couple weeks one summer. I was 15. Seatrain was recording in Marblehead Massachusetts.

He was living with Chrissy. A stunning woman. Stunning!

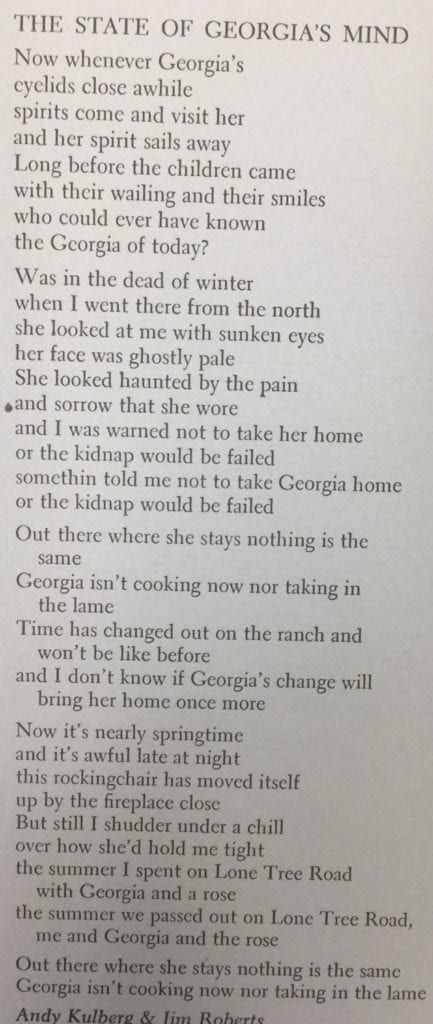

“Her hair was like a hurricane! Her eyes like forest pools. Her words were few and fine and fair. I fell just like a fool!”—Gramercy—Jim Roberts

They lived in a little colonial clapboard saltbox painted dark red. The huge fireplace which doubled for cooking in ancient days was nearly big enough to walk into.

He’d take me to rehearsals and to parties every night. I meet exotic followers of rock stars. Guys in suede jackets with hundreds of tassels. Girls in macramé tops and nothing underneath. I remember one was named “Rainbow.” I never saw those kind of folks in the suburban wasteland of Rockville, MD.

“They’re going to shoot the album cover tomorrow at dawn. Do you want to get up and go?”

They had concerts every few nights. Rehearsals every afternoon.

He’d take me to other concerts as well.

“Kris [Kristofferson], this is my brother Chuck.”

“That’s James Taylor!”

“He’s pretty busy right now. I’ll try to introduce you later.”

We’d go to the beach. He had a little MG convertible we’d somehow squeeze three people into.

“There’s George [Martin.] He doesn’t like to be bugged when he’s with his family.”

He was making a lot of money and spending it.

“Do you want to fly to New York with me? I have to meet with my agent. You can fly home from there.”

On the plane he handed me a magazine. It was the latest issue of Playboy.

“Check the ‘Girls of California.'”

There was Chrissy—with her sister.

Yikes! I was red faced.

Jimmie just laughed. Rock and Roll.

In Manhattan we took a cab to his manager/agent’s offices.

Grossman-Glotzer.

While they met I wandered around the place. Pictures of Bob Dylan, The Band, Janis Joplin, Peter Paul & Mary and others they represented hung from the walls.

There was a sample record room and I was told I could some pick out to take.

I snagged Todd Rundgren, Gordon Lightfoot, Jesse Winchester…and some others who never quite made and whose names have disappeared from my memory. But if I SAW their albums again…they would come to life I’m sure.

Then I was on a plane home to the dreary suburbs that sterile landscape of early 70s Rockville Maryland.

We’d see him when they’d perform nearby. The Cellar Door in Georgetown. Colleges and universities in the area. They made it to The Kennedy Center. I did too.

“That’s my brother!”

We didn’t make it to Carnegie Hall—but he did.

So long ago. But those memories of being a witness at the heights—courtesy of Jimmie—could be recalled any time.

I’d entertained a lot of friends in high school and college with stories of my brother’s accomplishments.

“Damn it, Jimmie. Why did you guys break up?” I thought.

Egos and planned solo careers grounded Seatrain. After a fourth mostly uninspired LP they all went separate ways.

Things didn’t really pan out for any of the boys…

Back to 2002…

I felt he might die that night he looked so ill. I took some of his medicine to knock me out. I could not have slept otherwise on his sad rumpled couch with those dreadful mechanical and organic rhythms beating in the background.

I woke in a strange room, into the strange morning light, into the strange sounds from the bedroom. I took him some Gatorade and Boost.

When the time seemed right I sat on the edge of his bed and said, “Jim, I’ve got to go back today. You’re welcome to come. I don’t know what you should do. Joe and Freddie will take good care of you, I’m sure. But I’ll come back and get you any time if you don’t want to leave with us today. But you’ve seen how fast this thing is going. If you wait too long you might not be able to go, even if you want to.”

He said nothing. Just stared at the wall behind my head. He massaged the long white fur on the back of Deuteronomy’s neck.

“Dude,” he whispered to her.

Joe and Tony arrived mid-morning to find me packing myself into the truck.

“It’s a long drive,” I said. “I want to get on the road as soon as possible.”

“Is he going?”

“I don’t know.”

They disappeared inside. A car pulled up behind me and a vision from my youth climbed out.

Larry Atamanuik had been the drummer when Seatrain, the rock group had reached its height. They were going to be the next Beatles. Even Rolling Stone had said so. George Martin who had produced the Beatles (many said he “was” the Beatles) came to the US to accomplish this. They’d scraped the sky but never quite left the atmosphere. I’d followed them as a very young teen in person, in print and on vinyl. I led Larry inside to visit Jim and left them alone to reminisce and make peace. I was still a fan. Of both of them.

After Larry left, Joe and Tony came out to the Suburban.

“He’s gonna go,” Joe said excitedly. “He said it’s time.”

“If we leave soon, we won’t get in too far after midnight,” I said. “Let’s move things along so he won’t change his mind.”

I began converting the truck into an ambulance.

We quickly hauled out the few things he wanted to take.

Dude, blessedly, was amenable to getting into the cat carrier.

The trip back through Tennessee and through the full length of Virginia was dreamlike. Driving east away from the sunset into the night.

Jim perked up. He sat upright during much of the daylight leg of the trip and didn’t use the oxygen tanks we’d loaded.

He called it: “My Last Road Trip.”

He watched the forests and mountains rushing by.

He, Joe and I spoke for a few hours until first one, then the other, dropped off and I drove alone into the morning.

As I drove into the dark, I wondered if Jimmie was dreaming. What was he dreaming?

I stopped to take a break and composed an email.

Subject line: Jim’s Last Road Trip:

whenever jimmie’s eyes close awhile spirits come and visit and his spirit sails away. long before the illness came with its wasting and its pain who could ever have known the jimmie of today…

we stopped at a tennessee roadside gas station. joe ordered a couple bologna and cheese w/ mayo mustard to eat on the road (he left his “picnic” in jim’s fridge)

i bought glass bottles frostie blue, peach and grape (no frostie root beer was left!)

jim pinched the peach from behind (prob not the first time.) then asked for one of the sandwiches and a cigarette…prob not a good idea. what was i thinking? why not?

time will tell if we (jim and bros) made the right decision.

I entered the addresses of friends and relatives and pushed Send.

Georgia was my Grandmother’s name…

Then the sky darkened and the highway turned northeast and we paralleled Skyline Drive before crossing the Potomac and landing in Frederick…in the Wonder Book parking where we’d left Joe’s Cadillac. We separated there. Alarmingly Deuteronamy got out of her cage and started to bolt. Mercy let Joe catch her and gently put her back in her crate. It was very late or very early when I finally got home.

Once ensconced at Joe and Freddie’s home in York, PA, Jim rebounded. Under our sister-in-law’s care, he visibly brightened. He began taking some food and looking less fragile.

The specialist and the internist were wrong. He had more than one month in him. And that time was mostly quality time. Thanks to Freddie, more than likely. He slept a lot but he was alert and in good spirits when he was awake.

I visited my dying brother at my oldest brother’s home as often as often as I could with my left arm locked at a ninety-degree angle by the cast. I’d had my arm sliced open and a surgeon screwed my bicep muscle into the bone with platinum screws. It would take 6 weeks until the cast was removed. It would take months to recuperate fully. I learned to be a right-handed bookseller. Penciling in prices. Buying books brought to the store. Ringing up sales. Even lifting and unpacking boxes.

He’d ask me for books. Mostly poetry. I’d pull them off the shelves and deliver them when I’d visit.

I’d always wanted to write beautiful songs like him. I tried…hundreds of times. I still do

One of the last visits I came up with this. (Don’t read it as “poem.” It’s just a story.):

big brother on jordan’s bank

when i was a child

a fever gripped me

angelic fantasies capered

on the bedclothes

spreading below my chin

“you see them there?”

i cried in joy.

“there’s nothing there”

my mother fretted

“sure. to be sure.

i see them too” he said.

then i rested assured

that two worlds exist

and either held a place for me.

now, with a foot in each

it’s my turn to assure

the withered frame

“i see it too”

and somehow

help him divine

where his comfort is

until our father’s voice calls

him home for good

Two months after his Last Road Trip, he awoke one morning disoriented. He told Freddie he wanted to dress for church. It was not the Sabbath. He sought the shower awkwardly. Both hands braced against the hall walls. Halfway there he turned back to his bed. Crawling the last few yards. That afternoon a coma took him. Joe called me and I made the hour and a half drive to York from the Fredrick store. I was out of my cast. Still, my arm was not fully functional. But that night I sat on the edge of his bed and played my 1975 Martin D 28—I’d bought it new in college with the little bit of spending money I’d gotten after Dad died. I sang every song I knew. Some of the songs were his. I sang my best for him. Just us two. I don’t know if he knew I was there. Within a day or two it seemed he was “gone.” His bloodshot eyes gazed at something not in this world. Hospice came and attached tubes and wires. But for periodic animal groans, an occasionally arching of his spine, he was quiet and motionless. Toward the end, his breathing became husky and then rattling. Then sporadic. I hope he was not conscious of this passage—so ugly, inhumane, it was. But I would still sing to him and play guitar as best I could. I hoped wherever he was he might enjoy it.

Brothers and their wives stood vigil. I prayed for him. I prayed for me. I prayed my end would come like a light switch. Full on and, in a millisecond later, full off. A few days later Tony called me at work to say he was gone—in every way.

The next morning I sent this email to family and friends:

James Talmadge (Jim) Roberts passed away at 4pm Oct 29, 2002 in York, Pa at the home of Mr & Mrs Joseph T Roberts. He had a 3 month battle w/ liver cancer.

He was a consummate poet artist and musician.

He attended the Univ of New York at Buffalo in the 1960s where, as an undergrad, he gave lectures on James Joyce.

He then went to NY City w/ his childhood friend, Andy Kulberg, where they formed the rock group SEATRAIN. The groups 2nd and 3rd Capitol Records albums were bestsellers. They were produced by George Martin and were the first project Martin worked on after the Beatles broke up. Jim wrote many of their songs including the hit single 13 QUESTIONS which rose to number 5 on the Billboard Chart. The group toured throughout the US and overseas. They played the Fillmores and Carnegie Hall. Jim’s parents were proud to see him onstage at the Kennedy Center.

After the group disbanded Jim moved to Marin County, CA where he continued writing. He worked w/ numerous writers and musicians including Peter Rowan, Robert Creeley.

He spent the last 2 decades in Nashville where he continued writing and had songs recorded by groups like New Grass Revival. He also began an intense course of Bible study and received many scholarship medals from the Methodist Church.

When he became ill he moved to his brother’s home in York where he was given wonderful care during his last weeks. He was very philosophic and patient during this time. His family and friends were very fortunate to spend many wonderful hours w/ him there. Brothers, nieces and nephews were able to reminisce about his many family and professional adventures. Like the time Janis Joplin interrupted a call home demanding help w/ a song. Or the time he told me to call back because Bob Dylan had stopped by to play guitar.

He was predeceased by his parents Joseph Thomas and Mary Gertrude. He is survived by brothers Joseph T. III, Alton O, Charles E. And his brothers’ children Joseph T. IV, Arthur Gerard, Kristin M, Sean J, Geoffrey, Gregory, Charles E T, Joseph T R. And numerous grand neices and nephews.

Some days later Nashville had this to offer:

Gifted poet, lyricist embraced God, bellman’s life

“Only nature has a right to grieve perpetually, for she only is innocent. Soon the ice will melt, and the blackbirds sing along the river which he frequented, as pleasantly as ever. The same everlasting serenity will appear in this face of God, and we will not be sorrowful, if he is not.”

— Henry David Thoreau, upon the death of his brother.

On Oct. 29, Nashville lost one of her most beautiful minds when noted lyricist, Bible scholar and bell captain extraordinaire James Talmadge Roberts lost a sudden three-month battle with cancer. He shared his last days with his brother Joseph and his family in York, Pa. Just as he lived his previous 58 years, at the end he was philosophical, poetic and patient.

When the popular Northeastern band Blues Project split up in 1968, bassist/flutist Andy Kulberg and drummer Roy Blumenfeld moved to the West Coast and teamed up with fiddle player Richard Greene to form Seatrain, possibly one of the most diverse musical acts of the time. Their four exceptional albums combined elements of rock, country and classical music, accented with a hint of psychedelia. The eclectic group of musicians had its own lyricist, a young and talented Jim Roberts.

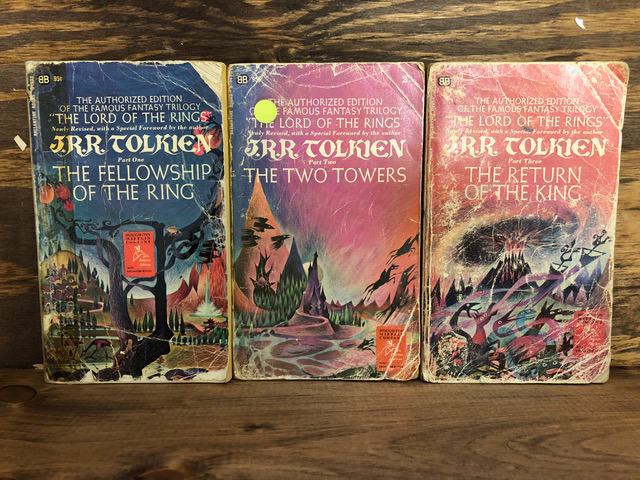

Roberts attended the University of New York at Buffalo during the restless 1960s, where, as an undergraduate, he became an authority on James Joyce, author of Ulysses. He then followed Kulberg, a childhood friend, to New York City and began writing songs. The duo created several thoughtful and artful classics such as Song of Job, 13 Questions, Out Where The Hills and As I Lay Losing.

Seatrain recorded its first self-titled album in 1969. After the band had toured America and received great reviews, Capitol Records quickly signed the band. The second LP, also titled Seatrain, was recorded in London in 1970, followed by Marblehead Messenger, a project that former Beatles producer George Martin abandoned before its completion the next year. These two albums received much critical acclaim, but fell victim to commercial indifference.

Consequently, the group’s final album, Watch, released in 1973, was its only Warner Brothers production. By the time the group disbanded a year later, Seatrain had played hundreds of venues, ranging from the Boston Tea Party to The Fillmore to Carnegie Hall.

Roberts came to Nashville almost two decades ago and continued to write songs, working with the New Grass Revival for a time. Meanwhile, the lyricist began an intense study of the Bible, earning many scholarship awards from the United Methodist Church.

He had a small apartment on 19th Avenue South with a patio overlooking Music Row, where he often entertained friends with his mandolin and romantic tales of worldly adventures. But eventually, he was no longer able to count on the music business for a living, evidenced by the framed royalty check he once received from BMI for the amount of one cent.

On Aug. 20, 1998, Roberts began working as a bellman for the historic Union Station hotel. This man, who often collaborated with Bob Dylan and once even told his mother that he had to call her back because Janis Joplin needed help with a song, could have become cynical. But Jim Roberts embraced his new job as a second career, demonstrating to all who knew him that he was much more than simply a gifted poet.

Before long, he became bell captain of the Wyndham International property. His affection for the abandoned train depot-turned-hotel, motivated by his inherent graciousness, was infectious. His writing skills soon crept into his new occupation when he wrote the self-guided tour brochure Union Station uses today.

Then on July 29 of this year, Roberts complained of a stomachache to co-workers Leroy Clay and Howard Muldrow, telling them he would see a doctor in the morning. At 11 p.m. that evening, he completed his final shift at his beloved hotel. To remember his colleague, Clay quietly saved the last work schedule that listed his dying friend’s name.

“That young man lectured Job until Job’s poor heart near broke, and from the whirlin’ wind, God Himself spoke,

“Sayin’, ‘Who’re these who claim to know my workings and all my ways? Job has proved his faith and shall live joyous days.’ Yes, Job lived joyful days. Oh, yes, he did.”

— From Song of Job by Jim Roberts & Andy Kulberg, 1970.

A couple weeks later, after the funeral and weeping and words and playing recordings of his songs, there was a resumption of normal life.

Then I flew to his home in Nashville. It must be cleared out so it may become someone else’s home. I was good at clearing houses. I did it for a living. The task fell to me.

And there I found myself before his books once again. Far more successful with letters than I, still, no book here bore his name upon its spine. Songs and poems and a trunk full of manuscripts. For many, many years his muse had abandoned him. Maybe.

He never expressed regret about that. Occasionally, he’d begin a project with fits and starts. Mostly he lived and worked at a job he would have scoffed at in his glory days. But he had learned. It’s trite certainly:

“It’s not what you do, but who you are.”

But the talent. The blank pages he could have filled. He should have filled.

He had expressed regret about Chrissy. A love he’d chased away so long ago. She was beautiful. A model. A gentle spirit. Later he’d allowed himself to be stolen by a witch—a crazy person—who took what little he had left. Then there was a string of others. Some I’d met. Some he’d only told me about on phone calls. Perhaps Chrissy had been his muse.

I thought of the new songs he’d write and sing to me over the phone late nights occasionally. He would drunk dial sometimes—often at two in the morning. Other times he would just call and chat about what was going on in Nashville. One was called “I Don’t Talk About Her Anymore.” He sang that song often.

Those calls would often anger me.

“Do you know what time it is?!”

Now I thought, “He’ll never call again. I wish I’d see his number on my phone one more time. I wouldn’t get mad.”

I stood still before his books.

I remembered the high school kid in Amherst.

The lithe athlete with the crooked grin appeared before me. Close cropped hair in the style before his rebellion. A tight white T-shirt with dark Lincoln green paint spots upon it. A thick paintbrush in his hand. Facing off with our father, as he did so often. My eyes widened as they had when myself, as a small child, observed this scene and heard words and tones that were not familiar to my young ears. He’d been painting the dark green trim on the house of my youth.

By the time I was 7 he’d left for the Big Apple, then Marin County and fame and (temporary) fortune.

Then I saw the dapper young rock star. Oh, he was a beautiful man. Then the aging bellhop who still had plans.

Then I was back. A child again with three big brothers. The Marine pilot, the College Professor and the Rock and Roll Poet.

Oh, to be home again with the family intact. To the child that was me, the family intact was to be a permanent situation. But my brothers’ departures and my parents’ decline taught me the lessons of the impermanence of life quite early on.

The books I’m standing before. All alone and far from my home, I began pulling them from the shelves as I’d done so many times before at less personal venues. I assumed the booksellers pose—on my knees—and I put them in boxes with automatic motion. I fold the flaps over my brother’s books and seal them shut.

I sealed his trunk of letters and manuscripts and memories. I boxed up anything else I felt should be saved and not donated or tossed away. We’d given his TV, computer…to his Nashville. I let his friend—who had helped so much—have the pickup truck for $100. Jim had been so excited when I’d lent him the money to buy it. He hadn’t had his own wheels for many years.

I carried the boxes and trunk out and set them on the little porch where he’d spent 20 years of evenings and mornings.

I called back to the warehouse and arranged to have the cartons picked up by FedEx and delivered there. Some of my brother was going back to Frederick. To Maryland.

That evening, I accompanied two of his best friends around town. They took me to all his favorite haunts and we celebrated his life. Late that night I went to the airport. I had a Gibson up very dry at the airport bar. Silently toasted Nashville and his friends and Jim. Then I flew home. And picked up my bookselling and young boys raising life where I had left off.

Someday, I’ll go through his trunk and boxes and try to find somewhere for his papers to go. They should be saved. He was there at the beginning. New York with the Blues Project and then to San Francisco for the Summer of Love.

A few months later the family flew to San Francisco. Some years before Tony had found a great house on Dolores St not far from the Old Spanish Mission. We rented a boat and headed toward the Golden Gate. Jim’s glory days of writing, singing and fame had been around the Bay three decades before. We took it west along the Marin County coast.

“Out wear the hills roll down to where the sea rolls in…”

Abiding Jim’s wishes, we were there to commit his ashes to the waters where his dreams had come true. The captain idled the boat just outside San Francisco Bay. The mighty orange red bridge soared above us.

Tony opened the wooden box. We said a brief prayer. Internally, I kept repeating the Lord’s Prayer like a mantra. That has brought me comfort in tough times my whole life. Tony tipped the box. The gray white sandy dust that was my brother slowly poured out. It hissed upon hitting the sea. Briefly a small patch of seawater was stained grey white before all was gone.

I returned home and put off no longer reprocessing and reshelving the books that were my brother’s. I made a special effort of finding new homes for all but a few which stuck to me. Those abide with me still.

Every once in a while I’ll google Seatrain. It is cool some—many—people remember. One night while be driven to a son’s soccer game and interacting with professional rare bookselling colleagues on a chatline a challenge was made. What rock songs can you think of that were made of books? A dozen or so emails dropped in from around the country. I googled Book of Job and this VERY BOOKISH rock video appeared. Somebody remembered! All those decades later: link to Seatrain’s Book of Job video.

It’s a long, long road

From which there is no return

While we’re on the way to there

Why not share

And the load

Doesn’t weigh me down at all

He ain’t heavy he’s my brother

Addendum. I flew to San Francisco a few days after I started this story. Perhaps the planned trip triggered this story. I was going to visit Tony in the city and my son Chuck at Stanford. My other son Joey accompanied me. On the plane, Joey expressed interesting seeing Alcatraz.

“Sure,” I thought, “I can get an image of the Marin coast for this story on the boat ride out into the Bay.”

The tour boat left Fisherman’s Wharf at 1PM. I looked west. Marin County—where the hills roll to the sea was completely blanketed in fog. The fog was pouring south gobbling up the Golden Gate Bridge where 15 years earlier we had buried my brother. It was stunning.

I thought “Tir Nan Nog.”

“Jimmie, are you there? Are you greeting me?”

GANDALF: End? No, the journey doesn’t end here. Death is just another path, one that we all must take. The grey rain-curtain of this world rolls back, and all turns to silver glass, and then you see it.

— JRR Tolkien — Into the West

PIPPIN: What? Gandalf? See what?

GANDALF: White shores, and beyond, a far green country under a swift sunrise.

PIPPIN: Well, that isn’t so bad.

GANDALF: No. No, it isn’t.

The next day the Marin Coast was clear and I could the hills rolling down to the sea and the spot where I last left my brother – until I see him again…

[…] (about whom I wrote a blog some time back) said cavalierly: “You might like these. They’re full of Elven spit and Dragon […]

Yesterday morning after listening to Marble head Messenger ( those two George Martin produced albums are amongst my most cherished lps ) I decided to Google search your brother’s name and came upon your beautiful and moving account of his last days. It was great to finally know something of the man who penned such masterpieces as Song Of Job . Thank you

Thank you so much Alastair!

I am glad you found it.

I hope Seatrain gets rediscovered someday. They were wonderful.

I was so lucky to tag along for the ride.

I really appreciate your writing.

It meant a lot.

Best

Chuck

Your brother’s lyrics were inspired. ‘As I Lay Losing’, ‘Outwear the Hills’, and “Broken Morning’ compare favorably to anything Robert Hunter or John Perry Barlow wrote. It’s a joy to listen to those old albums.

I’m glad you found the story!

Jim was a poet first and you can see that in the lyrics.

We all just wish he had written more.

Peter rowan once told me he offered Jim a per “word” monetary offer …

The blogs are searchable so if you are interested Jim, Jimmie, Jimmy appears in many others as well.

THANK YOU so much for writing. It is so heartening to hear from people who know the quality.

Maybe they will get rediscovered someday.

Best

Chuck