“Who you?”

I knew who he was. He was from down in the city and the top book dealer in the region. I was just a newbie book guy—unknown. His accent was from somewhere around New York—New Jersey? Long Island? I should know. I went to college with a lot of those folks. And I was only a few years removed from my years at Connecticut College. It had been Conn College “for Women.” The school had gone co-ed only a year or two before I arrived.

I told him who I was:

“I’m Wonder Book.” Very medieval. Like that was my title.

I turned and continued lifting the jumbled, crumpled, box lots into the back of my 1977, white, Ford F-150.

“I wouldn’t buy that crap.”

He turned and ambled off with five or six books under his arm.

“Thanks for the advice and screw you,” I mumbled to myself. I would have that second thought about him many times over the decades to come.

Estate auctions. Whether they were conducted at the end of a dusty, farm lane or on the wooden, wrap around porch at a Victorian Lady on a quiet, small town side street, there was always anticipation mystery and excitement in their aura. And not just a little show biz. This one was at the Frederick Fairgrounds in one of the old, airy, glass and brick buildings that houses prize vegetables or blue ribbon pies every year at the annual, county fair every fall for the last 155 years.

Was it 1983? Charlie Stup’s estate sale had made the front page in The Frederick News Post. He was a well-known businessman. Among other things, he ran the old Dan Dee Restaurant. That place was a landmark up on the mountain west of town for decades.

I’d seen him often in the old Farmer’s and Mechanic’s Bank where I’d stand in line every morning (excepting Sundays) to make the deposit of the previous day’s cash and checks. Short, bald, ebullient. He was quite popular with the tellers I would get to know so well for so long. I can still see their faces now. They’d sit on their stools across the chest high counter. Donna, Barry, Cindy…

The newspaper story reported the sale would be quite an event. Charlie was an inveterate collector of many, many things. He was also a well-known “pack rat.” I put the date on my calendar and made sure I had coverage at the shop all day.

Estate auctions are all-day events. There’s often little rhyme or reason as to what gets sold when. Indeed, the books could be sold at different times all during the day of the sale. Some could be in the attic contents. Some in the basement. Living room, bedrooms…They would sometimes stipulate, “The cars will be sold at noon.”

The big day came, and I pulled through the ancient, wrought iron gates of the Frederick Fairgrounds. I groaned. The parking lot was packed with vans and pickups and station wagons with trailers attached to their bumpers. I recognized some of the antique dealers, flea marketers, pickers, scouts, and hangers-on milling around outside waiting for the doors to open.

Country auctions. Mano-a-mano book buying against other dealers and the public.

The doors opened and everyone poured in. One wall was lined with tables where the “better stuff” would be sold one at a time.

I rarely did well buying things “one at a time.” It got so that if I, the “book guy,” was still bidding on an item, it must be a steal, so my bids became targets for amateurs competing with my “superior knowledge.” Indeed I was usually up against specialist collectors or booksellers who did, indeed, have superior knowledge for showcased, individual items.

I recall bidding up one up-and-coming “antique and collectible” dealer who clearly thought if I was still bidding the item must be a steal. It was a small, junky set of clothbound classics. The kind of thing you’d order from the back of a Sunday newspaper magazine. Eight volumes. I would have, reluctantly, retailed them for $1.50 a piece. This guy had been dogging me all day. Bidding up things I remotely showed interest in. I feigned excitement about this group as he upped my bid after every excited nod I gave to the auctioneer. If the book guy was so passionate about these, they must really be something. I acted agitated at his competition until we got to $70. I nodded vigorously. The auctioneer turned to the antique guy.

“80?”

“Yea!”

I abruptly turned and ducked away leaving the guy holding the box he’d over paid for by about 20 times its wholesale value.

Maybe that’ll teach him a lesson.

No, I’d stay away from the tables. Much of the building was box lots arranged in rows on the floor. That was more my style. There’d be sleepers in those boxes if I was any judge of Charlie’s breadth and depth. Auction companies pack in a hurry. They’ve usually only got 6-8 hours to sell off someone’s life long collection of everything from hand tools to bath towels.

I went to the table and registered. They knew me. They had my tax number on file. I was given a bidding card with a bold, red number at the top. Was I #172? Below that the card was lined so you could write the down the lot number, description, and the amount you bid as you went.

The hangers-on milled around the Methodist Ladies Concession stand cradling paper cups of steaming coffee and the inevitable ham sandwiches you could buy for a dollar. The Methodist ladies would carve the slabs of pink meat constantly until the sale started and the demand died down.

I went to the box lots and began peering into one after another. If there were books, I’d bend lower and flip through one after another. If the box looked good, I’d make a mark on the side of it. The box lots didn’t have individual lot numbers. If the box looked great, I’d add another mark. If it was REALLY great, I’d mark an “X” on it…and so forth. I did this surreptitiously—not wanting others to see what I was especially interested in.

Charlie’s collection was all over the place. Books, stamps, autographs, gemstones, watches, whiskey decanters, photos, and on and on. But so much of it was jumbled together—as if drawers had been pulled out and the contents dumped in boxes—as if tables or shelves had just been swept clean and into boxes. Maybe some of the boxes were of Charlie’s own creation. Things he’d bought and put in boxes and never got around to looking at again. Boxes from his garage or attic or basement.

The first auctioneer was a regular. I’d run into him before. Short, bearded. He held a microphone in one hand with a spiraling cord attached to a kind of boom box that he held in the other. I didn’t like him. He could get testy if you looked at him the wrong way or if he thought you weren’t behaving. But I didn’t let it show. You want the auctioneer to like you. You help him out and make him look good, and he’ll make sure he sees your bids and, maybe, knock down lots a little quicker for you than for others. He wants to get through the day and the longer the bidding stretches out—especially on the low end material—the more he has to talk and banter and cajole and sing his own particular “call” or “cry.” It’s not in his best interest to spend much time getting a bid up from $1 to $5.

He tapped the microphone.

“Can you hear me?”

Affirmative murmurs from the outer edges of the cluster of bundled up bidders growing around him. He soon became like a nucleus in an amoeba as the group of almost exclusively bundled up men moved in. We became like the fluid cell body moving and changing shape around him as he would go from spot to spot.

He had a spotter on one side of him. A “ringman” who would the scan the group looking for unseen bidders on the fringes and pointing them out to the auctioneer. On the other side was the recorder. She would write the winning bidder’s number and the dollar amount on a master list and on a detachable chit. She’d also write the lot number (if there was one) and a brief description of the item sold. The chits would later be torn off and sorted by bidder number at the auction table.

“I’m gonna begin with some box lots. In an hour or so, we’ll move to those first tables by the entrance awhile.* Then I’ll switch off to another auctioneer, and we’ll move back for more box lots. When I’ve said “Sold” and called your number, the item is your property and your responsibility. YOU need to take care of what you’ve bought. We are not responsible for any breakage or accidents.”

* “Awhile” is a regional colloquialism leftover from the early German settlers. Back then it wasn’t unusual to hear older folks say, “Outten your cigarettes” or “Red up you room.”

The briefest pause…

“We’ll begin with this box. 20! Do I hear 20? 20, 20, 20. 10! 10? 5! Come on you know you’re gonna get there. This’ll take all day if no one starts.”

I held up two fingers.

“2! I see 2. 3 over there. 4, 4? 4! 5! I got 5! 10?…”

And on it went. Box after box. When I’d win a box, I’d move in and drag it off to the side. I put my coat over them to keep the poachers out. Hell, some of these characters might even take my coat. However, in taking the box out, I’d lose my spot near the “nucleus” and the bidding continued unabated! Is he selling one of my !! boxes?!

I began blind bidding sometimes—bidding on boxes I couldn’t even see as I tried to jostle toward the center where the auctioneer moved from lot to lot.

“Damn!” I thought. “A lot of these bobos aren’t even bidding. They’re just in the group for the ‘show.'”

“Bid! BID!”—was that the first time I’d heard that voice? Could have been. It was the Book Muse who’s watched over me—and teased and tormented me—for all these years. Sometimes chiding. Sometimes warning. Sometimes reminding me of my many past mistakes and telling me I’m close to making another—”just like ye’ve done before.”

I bid and bid and bid on a box I couldn’t even see. But I saw the auctioneer’s eyes. He locked onto my eyes.

“50?”

I nodded.

“I have 50. 60? 60? 60?”

“Bid!” she whispered with an Irish lilt. Or was it Welsh? I swear she’s been both. The confusion is likely yet another tease. Women!

I nodded again. The auctioneer smiled and nodded back.

“I already have you,” he paused a moment and smiled at me:

“SOLD at 50 to 172.”

A couple dozen eyes turned to see who was bidding from the back. I didn’t want to be seen. Being anonymous at an auction is often a good strategy. I looked down, turned, backed away and circled the group to get closer to my box. The auctioneer was already crying out for bids on the next one. I looked at the box I’d bought for $50. That was a lot of money then. My weekly draw was $150. It was a tall box. Maybe 3 feet high. The kind of box movers use for clothes and linen and stuff that is bulky but doesn’t weigh a lot. I peered down into it.

“Drapes?! What have I done?”

“Ye’ll be fine. Now get back in there. There’s but a few boxes left in the row. He’ll be moving to the tables next and there’s not a thing there for ye.”

I dragged the box toward my stash. It had weight to it. Maybe there’s something in there.

Back to fray. Tempers were rising. Two bidders each thought they’d won the same box and were arguing over it. The auctioneer and his helpers had moved on. They’d be no help.

“No. You’d bid on THAT box,” one guy claimed pointing to a sad abandoned thing a few feet away.

We all moved on. Let them sort it out.

Soon we were all at the last box in the first row. It got knocked down for 5 bucks. To me.

He’d asked “5?” looking at me. I nodded.

“Sold! 172.”

We were now “friends” of the moment and for the rest of the day. I’d bid often and quickly—if low—to get things started so the auctioneer wouldn’t have to keep starting high and working down to a dollar only to have the bids rise up and up. Later he began knocking things down to me quickly—often preemptively. He had bigger fish to fry. The big-ticket items were on the tables. The box lots were to be blown through fast and dirty.

He moved to the tables and many of the group followed. Some others that had been hanging back joined them. They’d been waiting for the good stuff to come. I dragged my last box over to my pile and inspected them. About twenty were in my pile.

“Goddamn it. Its not here!” grumbled a voice about 10 feet away.

It was Dennie Duggan. He had a flea market downtown. He’d sit on a stool behind a glass case with a cigarette dangling from one corner of his mouth. He had a gold ring in one ear and a tattoo of “Eire” on his bicep. His battered, old van had a bumper sticker on it: “Bobby Sands—Free at Last.” There were twenty or so booths carved out in his ancient, little, wooden warehouse. Several of the booths were his—including a little “Rare Book Room” behind and beyond the counter where he’d always perch. You’d have to ask to go into it. I’d learned a lot in there. He was an old pro at country bookselling. And buying. We got along well. I’d often buy things just to get him talking or, more like, paying a little fee for the training he was giving me.

“Somebody took the feckin’ thing out of here. Switched it!”

This was not unusual. In the scrum of the quick pre-sale inspection, some unscrupulous buyers would move books from box to box. Either seeding one box with a lot of better books or, more likely, hiding a real treasure at the bottom of a box of beat up Grosset & Dunlap reprints of Zane Grey, or worse, Temple Bailey that others had already inspected and discounted as worthless.

I shook my head in commiseration and started stacking my boxes as best I could putting those without lids on the bottom layer and covering them with boxes that had flaps that could be closed.

I then wandered over to the tables to watch the action there. “Who You” was bidding on some single volume. It looked like a county history. I stayed back. Mike Stevens sidled up to me. He was a flea marketer and scout. He’d often bring me boxes of books he’d pick up here and there—after he’d taken what he wanted out of them.

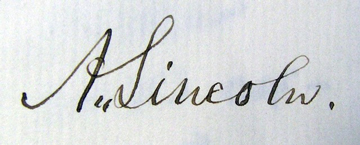

“The Lincoln is gone, Chuck.” His voice was low as if it was secret.

I knew what he meant. There had been a long letter penned by Abraham Lincoln. Maybe it was a letter of condolence to the widow of an Union officer he’d known. I don’t recall. I do remember the signature was big and bold.

I’d seen it during my cursory inspection of the table treasures when I’d first walked in. It was nicely framed. It had “walked” apparently. Likely under someone’s coat in the confusion of all the people milling about. I knew better than to try to bid on premium items. There were plenty of well-heeled, knowledgeable, antique dealers as well my expert “friend” from the City. Not to mention collectors of all sorts—specialists who likely knew values—retail and wholesale—in their field far better than I. It was they who were going to snag some of Charlie’s gems that fit into their particular niches.

It was nearing lunchtime, and the Methodist ladies were getting busy again with more ham sandwiches. They’d also ladle out cups of steaming bean soup. It was chilly in the unheated building—especially if you were one of the groupies just standing around chewing the fat and watching the action “on stage.”

A new auctioneer rotated in and we went back to the box lots. I had pretty much the same experience with him.

The day ended about three. I paid my tab.

“172? $540 please.”

Then I began rolling out the 60 or so boxes I bought on the two wheeled, hand truck I’d brought with me. I’d hustle back in to be sure no one was messing with my boxes while I was outside in the parking lot.

That’s when I had my “Who You?” encounter.

I was living in an old, Pennsylvania, limestone house on a little farm South of Gettysburg at the time. There was a bronze plaque attached to it: “Civil War Building.” Locals told me it had been a temporary hospital during the battle. I rumbled up US 15 along the Catoctins and South Mountain. The tall golden statue of the Virgin Mary looked down from halfway up the Mountain next to Mt. St. Mary’s College near the Grotto of Lourdes as I passed by. I crossed the Mason Dixon Line from Maryland and into Pennsylvania.

“I wonder what’ll be in those boxes?”

“Ahh, its great fun you’ll be having this evening.” Now I knew whose voice I was hearing. It was still disconcerting.

She, the Muse, was right. I backed to the garage and began taking boxes in. I rarely took work home. And never this much. But this was an exception. I opened a bottle of beer. Piel’s in short 12 oz bottles. At $4.99 a case, it was a great default beer when money was tight—which it always was back then. It wasn’t a bad beer either.

It was like Christmas—only profitable. Box after box yielded surprises. Presidential autographs, expensive stamps, a 300-year-old Arabic manuscript written on goatskin—other neat and exotic stuff. A little, nondescript, Fannie Farmer candy box yielded a dozen 3-cent pieces all in fine condition.

Charlie had wrapped them tightly in a linen handkerchief. The box didn’t jingle so the kids working for the auction had tossed it into a box. All kinds of cool whistles and bells emerged in paper, metal, glass, ceramics, cloth…

And books. Sweet luscious books! I’ve forgotten what they all were, but in those days when “good” books were few and far between, Charlie Stup’s sale stands out to this day as a watershed event. It had been a grand day for all the stress, jostling, and nervousness. I’d gained knowledge, confidence, strategies…and a Muse.

Auctions. I gave up on them long ago. I think the last estate auction I attended was about 15 years ago. It went ok. But it was a full day shot on stuff that was pouring in through the regular channels every day. Too much time. Too much work. I don’t mind hard work but I can’t see paying someone to stand around with me most of the day waiting for stuff to roll into the van.

And toting boxes out to the parking lot and lifting them into the van after standing all day—I graduated from that. Plus I was “known”—the Book Guy—and therefore a target.

Maybe if it was the estate of someone I knew. Someone I knew had some special things.

Nah. The days of scanning the classified ads trying to read between the lines of the dense Estate Auction ads are long gone.

Some ads would list only the word “Books.” 10? Or 10,000? In the old days, I might take a shot and show up. Or an ad would state “Lots of books.” 10? or 10,000?

No matter what I was gone for the day.

I’ll write more about auctions in the future. For there were memorable and important ones. But this story is about Charlie’s possessions.

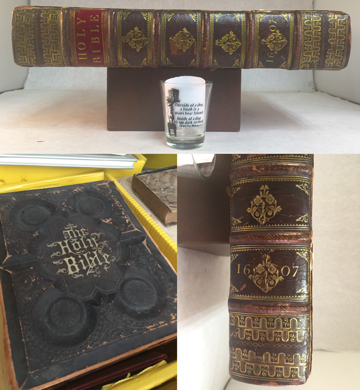

I do vividly recall one of the books that I found. It was in that tall box beneath the drapes and some junk books. When I got to the bottom of that box I saw a warm glow. It’s that soft, inviting, friendly brown, soft shine of old polished leather. Calf. I bent in and lifted it out.

“Just an old Bible,” I thought. The Bible is the most common old book. I see them every day. Really. I will likely see a few old Bibles on carts for me to inspect when I roll down the mountain and go into the warehouse on this Thanksgiving morning in 2017. They come in all shapes and sizes. Giant ornate tomes with intricately detailed metal clasps. Simple utilitarian bindings. They were published everywhere. And in many languages. I still come across a lot of German Bibles published in the United States in the 18th and 19th century.

“Yer goin’ to be a challenge. I can see that right from the start,” mused the voice.

I turned it round and round inspecting the boards and then the spine. It was in great shape with six raised bands and gilt decorations. “Holy Bible” was tooled in gold on a red, Morocco leather label in a compartment on the spine.

“Kind of primitive,” I opined.

“Primitive?! Look down!” she chided—rather harshly, I felt.

In the fourth compartment, or panel, down from the title, I saw the numbers “16” and “07” separated by an ornament tooled in gilt.

“1607…”

From my cold, poorly lit garage I was transported. London. 1607. Shakespeare.

This book had been THERE. In London. In the early 17th century.

It could have been in a wealthy merchant’s home not far from the Globe Theater. It could have been within earshot of the actors and their lines.

And now it was here. On my little farm in Gettysburg. In my hands. In my possession. Mine. For this lifetime any way. For I’d decided then and there I’d never give this book up. I was all of 27 years old.

It was the stuff dreams are made of.

My dreams.

What was happening in London and with Shakespeare at that time?

He had been in London likely since the late 1580s as an actor and playwright. Henry VI Part 1, his first play, was written around 1589-1590. The theaters were closed due to Plague from 1593. They were to close again from 1608-1610. By 1607, Shakespeare is thought to have written almost all of his greatest plays with Macbeth and King Lear thought to have been written in 1606. After 1607, only The Tempest stands out. Cymbeline, Timon of Athens, the lost play Cardenio, and few others were also written. His last, Henry VIII, is supposed to have been penned in 1613.

Queen Elizabeth died in 1603. King James had work being done on his Bible since 1604. It was first published in 1611. The Globe Theatre was opened in 1599, destroyed by fire in 1613 and reopened in 1614. Shakespeare died in 1616 on April 23. If some citations are correct that his birth was on April 23, 1564, then he died on his 52nd birthday. 36 of his 37 of his plays were gathered by his friends and fellow actors James Hemminges and Henry Cordell and published in 1623. That book is now known as the First Folio. Thereby, they “#BookRescued” the greatest body of literary works in the world. Anne Hathaway, Shakespeare’s wife, passed away the same year. In Will’s will, he had left her his “second best bed” adding more mystery to his sparsely documented life.

Other people of that time: Christopher Marlowe, Edmund Spenser, Sir Francis Bacon…

Other events? The defeat of the Spanish Armada, the founding of the Bodleian Library Oxford, the Gunpowder Plot…

1607 saw the founding of the Jamestown settlement in the Virginia colony. The flight from religious persecution and to new and unknown opportunities in the New World was just beginning.

That year also saw the Thames River freeze over in the Great Frost.

But what about the 1607 Bible? “MY” Bible.

It is a Geneva Bible.

Here’s what one online seller has to say about it:

The Geneva Bible was the ‘Bible of the Protestant Reformation’, and the Bible of the Puritans and Pilgrims. It was the first Bible taken to America, brought over on the Mayflower. The Geneva Bible is the Bible upon which America was founded. You can imagine, most early American colonists, who were fleeing the religious oppression of the Anglican Church (Church of England), wanted nothing to do with the King James Bible of the Anglican Church!

(link)

Textually, the Geneva Bible offered a number of radical never-before-seen changes: It was the first Bible in English to add numbered verses to each chapter of scripture. Also, the Geneva was the first Bible to introduce easier-to-read ‘Roman Style Typeface’ rather than the ‘Gothic Blackletter Style Typeface’ which had been used exclusively in earlier Bibles, although subsequent printing of the Geneva Bible offered people the choice of both styles of type font. Another curious innovation; the Geneva was the first ‘Study Bible’ with extensive commentary notes in the margins.

The Geneva Bible is the version quoted from hundreds of times by William Shakespeare in his plays. First printed in 1560, and also called the ‘Breeches Bible’, the Geneva Bible is the only Bible ever able to outsell and exceed the popularity of the King James Bible, as it did in the early 1600’s until its printing ceased in 1644. In fact, one of the greatest ironies of history, is that Protestants of all denominations today embrace the King James Version of the Bible (which reads 90% the same as the Geneva), even though the King James Version is not a Protestant Bible (it’s Anglican / Church of England). Most Protestants have never even heard of the Bible of their own heritage: the Geneva Bible. It was produced by John Calvin, John Knox, Myles Coverdale, John Foxe, & other English refugees in ever-neutral Geneva, Switzerland… fleeing the persecution of Roman Catholic Queen ‘Bloody’ Mary in England.

It’s not worth a lot of money. Maybe a few thousand dollars in 2017.

What did I learn that day? How did it change everything in my life?

I’d picked up a Muse.

“Picked up?!! ‘Twas yerself I chose, and I’m already having second thoughts!”

Ummm… I’d been found by a Muse. Selected as it were.

I learned that many of those with a lot more experience and “knowledge” in the book trade weren’t necessarily experts at everything. I’d learn they all had their blind spots and prejudices—which I could exploit to get my foot in the door. I’d learned to look at what they pass over with a critical eye. They don’t know everything.

That translated to my fledgling bookstore where I would stock anything that would sell. From series romances to comic books to rare modern and ancient collectibles. A book is a book is a book. And I would not look down on any one who liked and wanted books. Who knows, much of my early reading as a child was comic books. I eventually moved on from them. Putting aside the toys of youth. I would not show any prejudice to any book or any customer or reader. As a practical matter—Frederick was still a small, rural exurb of Washington and Baltimore. It was growing rapidly and would soon boom into Maryland’s second largest city. But back then Wonder Book needed every customer, every book it could resell. And it desperately needed every dollar that came in to survive to the next “first of the month.”

It was the beginning of a business philosophy that was to evolve over the next couple decades. Take EVERYTHING and sort it out later. Harvest everything in a collection and try to do something with every piece of it. Nose to tail bookselling.

It was also a very early high point to the serendipity, the treasure hunting aspect, the magic of finding and buying books.

That book knocked my socks off. Still does.

Those were the things I learned that day as a rookie jostling around that big, cold building with the experienced auctioneers and antique dealers and established booksellers and collectors.

“And…?” There my Muse is again…I’m glad she still drops in from time to time. She brings me great comfort—as well as discomfort.

“And…!?!” she inquires again with more urgency.

Oh, yeah:

“Always trust your muse.”

There are no comments to display.